Chapter: Nutrition and Diet Therapy: Diet During Childhood and Adolescence

Diet of Children Ages 1 to 12

CHILDREN AGES 1 TO 12

Eating habits develop

during childhood. Once developed, poor eating habits will be difficult to

change. They can exacerbate emotional and physical prob-lems such as

irritability, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and illness.

Because children learn

partly by imitation, learning good eating habits is easier if the parents have

good habits and are calm and relaxed about the child’s. Nutritious foods should

be available at snack time as well as at meal-time (Figure 13-1), and meals

should include a wide variety of foods to ensure good nutrient intake.

Parents should be

aware that it is not uncommon for children’s appetites to vary. The rate of

growth is not constant. As the child ages, the rate of growth actually slows.

The approximate weight gain of a child during the second year of life is only 5

pounds. In addition, children’s attention is increasingly focused on their

environment rather than their stomachs. Consequently, their appe-tites and

interest in food commonly decrease during the early years. Children between the

ages of 1 and 3 undergo vast changes. Their legs grow longer, they develop muscles,

they lose their baby shape, they begin to walk and talk, and they learn to feed

and generally assert themselves (Figure 13-2). A 2-year-old child’s statement

“No!” is his or her way of saying “Let me decide!”

As children continue

to grow and develop, they will increasingly and healthfully assert themselves.

They want and need to show their growing independence. Parents should respect

this need as much as possible. Children’s likes and dislikes may change. New

foods should be introduced gradually, in small amounts, and as attractively as

possible. Allowing the child to assist in purchasing and preparing a new food

is often a good way of arousing interest in the food and a desire to eat it.

Children

should be offered nutrient-dense foods because the amount eaten often will be

small. Fats should not be limited before the age of 2 years, but meals

Whole milk is recommended until the age

of 2, but low-fat or fat-free should be served from 2 on. The guideline for fat

intake is 30% to 35% of calories from fat for 2- to 3-year-olds and 25% to 35%

of calories from fat for 4- to 18-year-olds, with no more than 7% from

saturated fats. It is recommended that children not salt their food at the

table or have foods prepared with a lot of salt.

Young

children are especially sensitive to and reject hot (temperature) foods, but

they like crisp textures, mild flavors, and familiar foods. They are wary of

foods covered by sauce or gravy. Parents should set realistic goals and

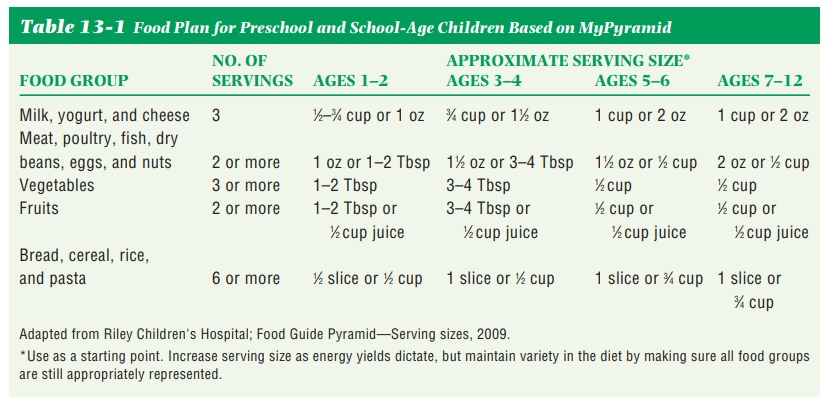

expectations about the amount of food a child needs. A good rule of thumb for

preschool children is 1 tablespoon for each year of age. Table 13-1 details

serving sizes according to age. Calorie needs will depend on rate of growth,

activity level, body size, metabolism, and health.

Children

can have food jags, such as eating only one or two foods, or rituals, such as

not letting foods touch on the plate or using a different spoon for each food

eaten. Choking is prevalent in young children. To prevent choking, do not give

children under 4 years of age peanuts, grapes, hotdogs, raw carrots, hard

candy, or thick peanut butter.

A

child needs a snack every 2 to 3 hours for continued energy. Children often

prefer finger foods for snacks. Snacks should be nutrient-dense and as

nutritious as food served at mealtime. Cheese, Cheerios, fruit, milk, and

unsweetened cereals make good snacks.

Mealtime

should be pleasant, and food should not be forced on the child. The parent’s

primary responsibility is to provide nutritious food in a pleasant setting, and

the child’s responsibility is to decide how much food to eat or whether to eat,

according to child expert Ellyn Satter (1995). When a child is hungry, he or

she will eat. Forcing a child to eat can cause disordered eating and,

ultimately, chronic overeating, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia.

Calorie and Nutrient Needs

The

rate of growth diminishes from the

age of 1 until about 10; thus, the caloric requirement per pound of body weight

also diminishes during this period. For example, at 6 months, a girl needs

about 54 calories per pound of body weight, but by the age of 10, she will

require only 35 calories per pound of body weight.

Nutrient

needs, however, do not diminish. From the age of 6 months to 10 years, nutrient

needs actually increase because of

the increase in body size. Therefore, it is especially important that young

children are given nutritious foods that

they will eat.

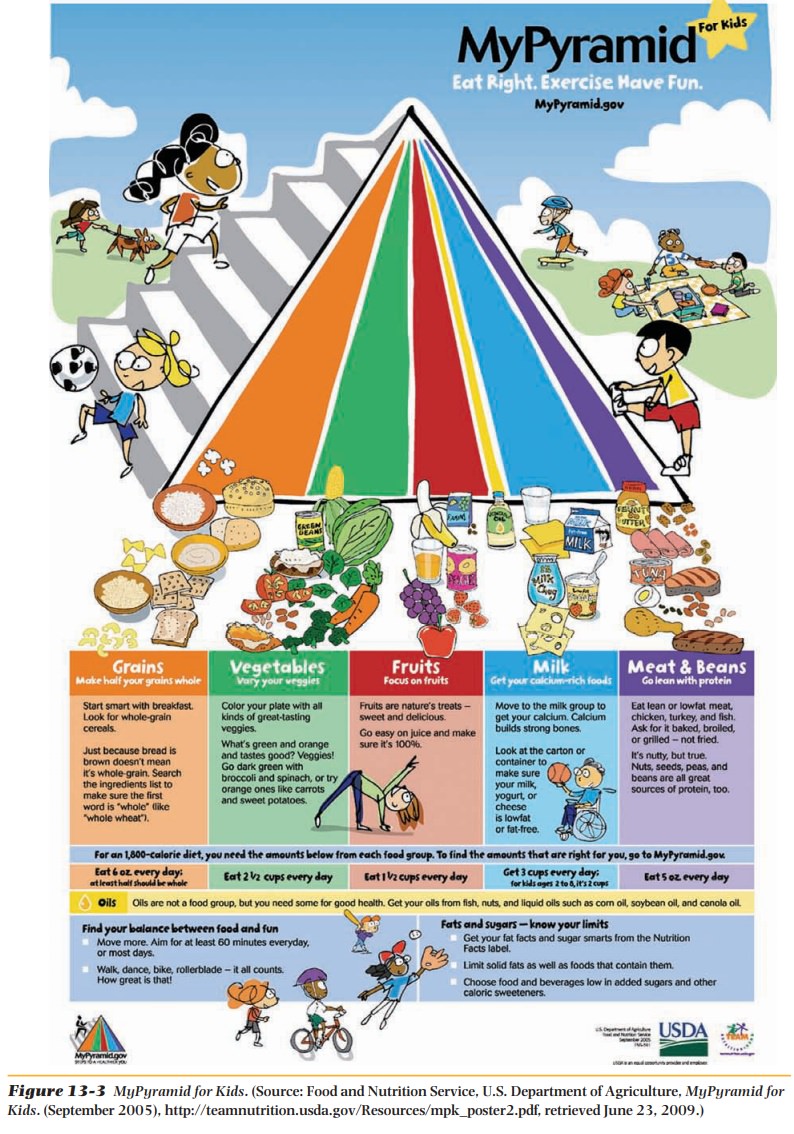

MyPyramid

(Figure 13-3) is a good foundation for developing meal plans that, with

adjustments, will suit all family members. A variety of foods should be

offered, and, when possible, the child should be offered some choices of foods.

Such a choice at the table helps the child’s psychosocial development.

In general, the young child will need 2 to 3 cups of low-fat or fat-free milk each day, or the equivalent in terms of calcium. However, excessive use of milk should be avoided because it can crowd out other iron-rich foods and possibly cause iron deficiency. The selections of the other food groups are the same for adults, but the portions will be smaller. The use of sweets should be minimized because the child is apt to prefer them to nutrient rich foods. Sweet-ened fruit juices, especially, should be limited. Children also need water and fiber in their diets. They need to drink 1 ml of water for each calorie. If food valued at 1,200 calories is eaten, then five 8-ounce glasses of water are needed. Fiber needs are calculated according to age. After age 3, a child’s fiber needs are “age + 5 grams” and no more than “age + 10 grams.” A child who eats more fiber than that might be too full to eat enough other foods to provide all the calories needed for growth and development. Fiber should be added slowly, if not already in the diet, and fluids must also be increased. Childhood is a good time to develop the lifelong good habit of getting enough dietary fiber to prevent constipation and diseases such as colon cancer and diverticulitis.

Childhood Obesity

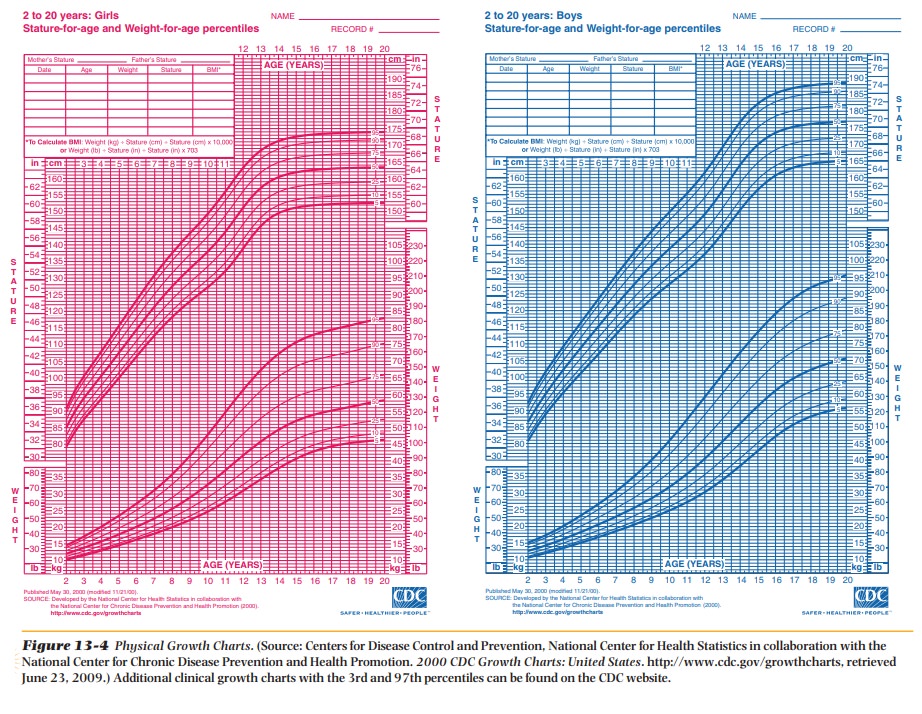

Normal stature and

weight for children can be determined using standardized growth charts (Figure

13-4). Expected growth patterns will fall between the 5th and 95th percentile;

children whose weight falls outside those parameters need special evaluation

and attention. Childhood obesity has become an epidemic. Overweight has doubled

in the last 20 to 30 years, and one in five children is now overweight. The

definition of overweight is a child at or above the 95th percentile of body

mass index (BMI) by sex and age. Children are considered obese when their body

fat exceeds lean muscle mass. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, rarely seen before in

children, is now being diagnosed in children as young as 10; it is related to diet

and weight.

Childhood obesity is

the result of an imbalance between the calories a child consumes as food and

beverages and the calories a child expends for normal growth and development,

metabolism, and physical activity. The bottom line is that calories eaten and

calories expended must be balanced. There is no single factor that causes

childhood obesity. An imbalance can result from the influences and interactions

of a number of factors, including genetic, behavioral, and environmental.

Genetics cannot be

solely to blame for childhood obesity. The genetic factors of the population

have not changed in the past 30 years, but the prevalence of overweight and

obese children has tripled during this time. If one parent is obese, there is a

50% chance that their children will be obese. If both parents are obese, the

risk increases to 80%.

Certain behavioral

factors can contribute to an energy imbalance and therefore obesity. Energy

intake of large portions of food and beverages, eating meals away from home,

frequent snacking on energy-dense foods, and consuming beverages with sugar are

all contributing factors for obesity. Chil-dren drinking sugared beverages may

not compensate for these additional calories at mealtime.

Physical activity is

important for children to help burn excess calories eaten. Obese children and

adults have similar health problems. Physical activity will help increase bone

strength and decrease blood pressure and prevent type 2 diabetes, sleep apnea,

and hyperlipidemia. Many schools have discontinued physical education,

especially for adolescents, but recess still continues for younger children. GET MOVING! Obese children have an 85%

chance of being obese adults if they are obese after the age of 10. Physical

activity can be as easy as walking for 60 minutes per day.

Many children with

working parents are not allowed to leave the house after returning from school.

Sedentary activities, such as watching TV and DVDs, playing computer games and

handheld electronic games, and eating, become the norm. There is a high

correlation between watching TV and obesity. TV can contribute to poor food

choices, excess snacking, and low metabolism.

Environmental factors, including the home, child care, school, and community, can influence a child’s behavior related to food and physical activity. In the home, children will imitate their parents in many ways, including eating habits and physical activity.

Child

care is an important place where healthy eating and physical activity habits

can be developed. Approximately 80% of children with working mothers spend 15

to 40 hours per week at day care. Parents need to check the menu and activity

schedule on a weekly basis.

Children

ages 5 to 17 are enrolled in school, which is a positive envi-ronment in which

to teach healthy eating and the importance of physical activity. Unfortunately,

the government is not helping, and many of the foods served in school

cafeterias are government subsidies. They are generally high-calorie, high-fat

foods that must be deep fried before serving. Butter and cheese sometimes are

included in these subsides. Vending machines are in many schools and, if not

stocked with healthy foods, can contribute to obesity.

Leaders in the

community must create an infrastructure conducive to physical activity like

sidewalks, safe bike and walking trails, parks in neighbor-hoods, and a safe

environment in which to participate.

Snacking and portion

control seem to be big issues with obese children. All foods can be fattening

if eaten beyond needs. Children should not be put on a “diet.” Children

continue to grow, so if weight can be maintained by exercise and portion

control until growth catches up, the problem of obesity will no longer exist.

An obese child, like a

child of normal weight, may need a snack after school. Make that snack a

healthy choice, such as a medium-sized piece of fruit, vegetables (using salsa

or fat-free ranch dressing as a dip), a 100-calorie bag of microwave popcorn,

or a single serving of cereal. Single-serving-size bags or premeasured portion

controlled snacks are ideal because an obese child will be likely to overeat

when eating from a large bag. Help children avoid drinking their daily caloric

needs with pop (soda) or other sweetened drinks. If junk food and sweetened

drinks are not purchased, they cannot be consumed.

What can parents do to

help their children? Talk to a dietitian or a nurse for some ideas like the

following:

• Understand that this is a family problem and that the entire

family will be involved in the solution.

• Help your family balance their calories. One part of balancing

is tosupply adequate nutrition and help everyone develop healthy eating habits.

• Develop healthy eating habits by doing the following:

o Provide plenty of

vegetables, fruits, and whole-grain products.

o Include low-fat or

nonfat dairy products.

o Choose lean meats,

poultry, fish, lentils, and dried beans for protein.

o Serve correct portions

(see Figure 17-3).

o Encourage everyone to

drink lots of water.

o Limit sugar-sweetened

beverages.

o Limit consumption of

sugar and saturated fat.

o Learn to make favorite

dishes healthier. For new ideas about adding fruits and vegetables to your

family’s diet check out the recipe database from http: // www.

FruitsandVeggiesMatter .gov.

o Remove calorie-rich

temptations. Allow your children to eat them “sometimes” so that they will be

truly a treat.

Remember that small changes every day can lead to success.

To continue the

progress made with healthy eating, everyone must participate in one or more

forms of physical activity each day for 60 minutes, such as the following:

• Brisk walking

• Playing tag

• Jumping rope

• Playing soccer

• Basketball

• Swimming

• Riding bicycles

• Dancing

In addition to

encouraging physical activity, help children avoid too much sedentary time.

Quiet time for homework and reading is fine.

Obese children and

adolescents are targets of social discrimination. This begins early in a

child’s school career, and the psychological effect can be devastating, causing

low self-esteem, which in turn may hinder academic and social functioning.

This may seem like a

monumental task for parents, but it is well worth it. Not only will their

children change their eating habits and start a lifelong exercise program, but

so will they.

What Can Parents Do to Help?

• Provide only healthy, nourishing food for meals and snacks. If

it is not available a child cannot eat it.

• Limit TV and computer time. Remove TV sets from your child’s

bedroom.

• Get moving yourself. Exercise benefits everyone.

• Never tell a child he cannot have a food because “he is too

fat.”

• Learn correct portions, even if this means weighing and

measuring (see Table 13-1).

• Remember, there is nothing a child cannot eat; it is just how

oftenand how much will be consumed of a particular food. There are no good or

bad foods.

• Never provide food for comfort or as a reward.

• Eat only at the table and at designated times.

• Give water to drink rather than calorie-laden fruit juice. If a

childwon’t drink water, then a small amount of juice can be mixed with water to

give flavor. Use 1⁄ cup juice to 8–12 ounces of water. This 4 glass of

water-juice will contain about 30 calories versus 120–180 for 100% juice.

• Eat slowly—it takes 20 minutes for the brain to get the message

that the stomach is full. Make it a game—set a timer and see who can make the

meal last for 20 minutes.

• Use the 20-minutes technique if your child wants a

calorie-densesnack such as cookies, chocolate, candy bars, or other

calorie-dense foods. The child must set the timer, sit at the table with a

portion-controlled serving, pay attention to the treat, and make it last for 20

minutes. Holding it in the mouth and rolling it around on the tongue will

satisfy taste buds quicker than swallowing immediately and may contribute to

satiety sooner.

• Learn to determine whether your child is really hungry or

justbored, tired, or lonely. It takes 3 to 4 hours for a stomach to completely

empty after a significant meal, so if that amount of time has elapsed, then

your child is truly hungry.

• Make sure your child gets enough sleep (8–10 hours per night),

as sleep deprivation has been linked to obesity.

• Change any unhealthy habits you may possess. You are your

child’steacher.

Preventing and

reversing childhood obesity will also decrease the incidence of obesity-linked

type 2 diabetes.

Childhood Type 2 Diabetes

As a result of the

increase of childhood obesity, there is a parallel increase in diabetes,

particularly type 2. Type 2 diabetes is normally found only in adults, usually

after the age of 40, and is associated with weight. Most obese children will

develop type 2 diabetes between the ages of 10 and 14.

Children with type 2

diabetes should see a certified diabetes educator to learn what to eat to

control their diabetes. The diabetes educator will also prescribe daily exercise

and attention to fiber intake, both of which help control blood glucose.

Increasing nutrition

and exercise knowledge of parents and children appears to be the only way to

prevent obesity and childhood type 2 diabetes.

Osteoporosis and Cardiovascular Disease

Children and

adolescents live in the moment. This creates problems associated with

osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases. Adherence to sound nutrition

principles during childhood and adolescence are needed to protect the heart and

bones.

Calcium must be

consumed at the DRI level until the age of 30. Fat intake should follow the

American Heart Association recommendations of 7% saturated fat, 8%

polyunsaturated fat, and 15% monounsaturated fat while keeping total fat to 35%

of daily calories.The typical diet of a teenager contains too much saturated

fat and soda and not enough milk. These habits lead to adult health problems.

Motivating children and teens to change their habits will be a challenge but

needs to be done.

Related Topics