Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Communication Disorders

Diagnosis - Childhood Disorders: Communication Disorders

Diagnosis

Phenomenology

Expressive Language Disorder

This condition varies with age and severity.

Vocabulary, word-finding, sentence length, variety of expression and

grammatical complexity may all be reduced. Most children with the

develop-mental subtype of this disorder demonstrate delayed language

development. Often auxiliary words or prepositions are omitted, resulting in

telegraphic speech: “he was going to school” becomes “he going school”. Word

order may be garbled: “Him like too me” for “I like him, too”. Words or phrases

may be repeated to the degree that speech may be echolalic, perseverative, or

both. Con-versation may be tangential, with sudden inappropriate changes of

topic, or conversely, perseveration. Pragmatic difficulties, such as in

initiating or terminating conversations, are seen, as is avoidance of

conversation. These children frequently are regarded as socially inappropriate

or inept, and at times may be suspected of having a formal thought disorder or

a Pervasive Developmental Disorder. They frequently have academic problems

because of their diffi-culty in responding verbally to exercises. They may have

motor coordination problems and various other neurodevelopmental

ab-normalities, documented upon neurological examination, EEG, or neuroimaging,

although no consistent patterns are seen.

Mixed Receptive-expressive Language Disorder

Children with this disorder may have all the

problems of Expres-sive Language Disorder. In addition, they do not understand

all that they hear. The deficits may be mild or severe, and at times

deceptively subtle, since patients may conceal them or avoid in-teraction. All

areas and levels of language comprehension may be disturbed. Thus the child may

not understand speech that is rapid, certain words or categories of words, such

as abstract quan-tities, or types of statements, such as conditional clauses.

These children may seem not to hear or attend, or to misbehave by not following

commands correctly. At times, when conversation is redirected to them in a

slower or more concise fashion, they may understand and respond belatedly, and

thereby be accused of willful avoidance. More severely impaired children may

not fol-low the rules of syntax or word order, and thus confuse subjects and

objects or questions and declarations. Often in more severe cases, disabilities

may be multiple and pervasive, affecting pro-cessing, recall and association.

Such deficits have immense social consequences.

Phonologic Disorders

This category is characterized by persistent errors

in the pro-duction of speech. These include omission, substitution or

dis-tortion of sounds. Omissions include single or multiple sounds: “I go o coo

o the but” (I go to school on the bus); or “I re a boo” (I read a book).

Substitutions include w/l, t/s, w/r, and d/g

“I taw a wittle wed wadio. It pwayed dood music”. Lisping, the frontal

or lateral misarticulation of sibilants, is a common distortion. Defects in the

order of sounds or insertions of extra-neous sounds may also be heard: “catht”

for “cats”. The occur-rence of these errors is persistent but not constant.

Usually only some sounds are affected. Some articulation errors are expected in

early childhood, especially involving sounds that are usually mastered at a

later age (in English, /l/, /r/, /s/, /z/, /th/, /ch/); these errors are not

regarded as pathological unless they persist and result in adverse consequences

to the individual. Ninety percent or more of children have mastered the more

difficult sounds by age 6 to 8.

Stuttering

Stuttering is the most easily recognized

communication disorder. It varies in severity among individuals. It may vary

over time and circumstance. It is typically more severe when the affected child

is stressed or anxious, and especially when communication is ex-pected. Because

of its often gradual onset, children are at first frequently not aware of its

presence. Over time they may become more anxious and withdraw from

conversation, as the degree of social discrimination they experience increases.

Stuttering may be accompanied by various movements which may seem either to

express or discharge anxiety, such as blinking, grimacing, or hyperventilation.

Children who stutter may sing or talk to them-selves without difficulty.

Sometimes children may attempt to stop stuttering by slowing down or pausing in

their speech; but this is frequently unsuccessful and leads to an exacerbation.

Thus a pat-tern of habitual fear and avoidance emerges.

Communication Disorder Not Otherwise Specifi ed

This category, used to include disorders that do

not fit the criteria for any of the other Communication Disorders, is generally

used only to describe disorders of voice, including pitch, intonation, volume,

or resonance. Hyponasality is characterized by the “ad-enoidal” speech

simulated by speaking with the nose pinched. Hypernasality, secondary to

velopharyngeal insufficiency, may be associated with serious voice problems.

Air escapes into the nasal cavity, resulting in nasal air emission, snorting or

a nasal grimace during speech.

Assessment

Interview and Observation

The psychiatrist seeing children must be familiar

with normal milestones of speech and language development and ask the parents

or guardians about the child’s speech and language, both past and current. Much

can be learned from even a few questions: Does the child seem to hear and

understand what is being said? Does the child require visual prompts? Does the

child in fact use spoken language to communicate? How long and complicated are

his sentences? Does the child “make sense” to outsiders? Can she be clearly

understood, even by strangers? Which sounds does the child find difficult? Does

the child use unusual volume, pitch, or nasality? Does he observe the rules of

conversation? Parent–child communication should also be observed.

For younger children, assessment may best be

carried out in a play situation. Rutter (1987) recommends that the clinician

assess inner language, comprehension, production, phonation and pragmatics.

Inner language means symbolization, which may be observed in the child’s

representational use of play ma-terials. Comprehension is assessed through

conversation and the use of developmentally appropriate questions and commands,

especially with nonverbal augments or prompts. The clinician should note how

well a child can follow and draw inferences from a conversation. Production

refers to speech, its fluency and intel-ligibility. Pragmatics are those

aspects of language that render it useful for social communication beyond the

most concrete level. Does the child appreciate the nuances of her partner’s

conver-sation, as, for example, when they signal beginnings and end-ings of

conversations, topic changes, or the patient’s turn to talk? Pragmatic language

involves nonverbal elements. Deficiencies in this area impair abstraction and

may render the individual almost “robot-like”.

In all cases, observations should be made in as

relaxed a fashion as possible, avoiding interrogation or rote exercises. If a

child fails to communicate a given item, necessary help, in-cluding nonverbal

prompts, should be offered, so that the child has the experience of success. A

sense of failure will stifle communication.

All of the phenomena seen in a clinical interview

may also be pursued in school settings, and teacher input is essential in the

evaluation of these children.

Developmental and Cultural Influences

The need for a clinician to be aware of normal

developmental expectations has been cited. Special sensitivity must be

exer-cised for the range of accents, dialects and conversational styles encountered.

English is spoken in an extraordinary range of patterns even within each

dialect group. It is essential that one does not pathologize differences in

intonation or dialect. Many American children grow up in multilingual

environments, and speak with a synthesis of languages, especially during their

pre-school years. Finally, children of minority groups who have suf-fered

social discrimination and children who live in physically dangerous

environments may necessarily be cautious and less forthcoming with language;

this may be adaptive in some cases and not a disorder at all.

Differential Diagnosis

Expressive Language Disorders and Mixed Receptive-expressive Disorders

These disorders are distinguished from each other by the pres-ence or absence of receptive problems. Children with autism may have any or all of the characteristics of the language disorders. However, they have many additional problems including the use of language in a restricted and often ste-reotypic fashion, rather than for communicative purposes. They also have difficulties with a wider range of interactions with persons and objects in their environment, and exhibit a restricted range of behaviors. The language impairments of mental retardation, oral-motor deficits, or environmenta deprivation are not diagnosed in this category unless they are well in excess of what is expected. Language impairment due to environmental deprivation tends to improve dramatically with environmental improvement. Sensory deficits, especially hearing impairment, may restrict language development. Any indication of potential hearing impairment, no matter how tenuous, should prompt a referral for an audiologic evalua-tion. Obviously, hearing and language disorders can and do coexist. Some children develop an acquired aphasia as a com-plication of general medical illness. This condition is usually temporary; only if it persists beyond the acute course of the medical illness is a language disorder diagnosed. A very se-vere acquired language disorder is seen in Landau-Kleffner Syndrome (acquired epileptic aphasia), accompanied by sei-zures and other CNS dysfunctions, and usually occurring between the ages of three and nine.

Phonological Disorder and Stuttering

The conditions should be distinguished from normal

dysfluen-cies in young children. For example, misarticulation of some sounds,

such as /l/, /r/, /s/, /z/, /th/, and /ch/, is common among pre-schoolers and

resolves with age. As with the language disorders, these diagnoses are given in

the case of motor of sensory deficit, mental retardation, or environmental

deprivation only if the dis-order is much more severe than expected in these

conditions. Problems limited to voice alone are included under Communica-tion

Disorder NOS.

Formal Speech and Language Assessment

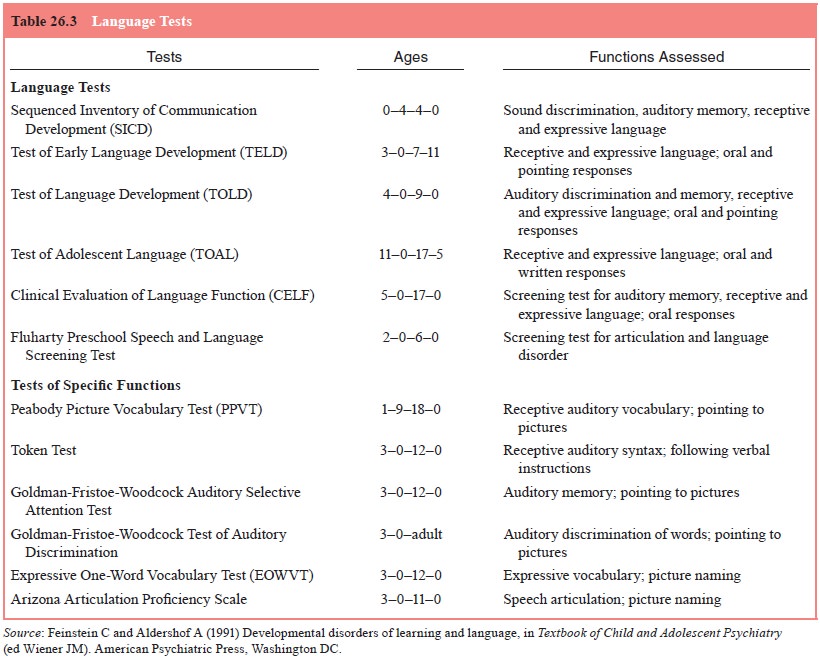

A number of instruments are available for the

assessment of communication. Some of these are listed in Table 26.3. Most are

beyond the training of physicians, whose most important con-tributions are

interview skills and medical assessment; but a fa-miliarity with them can help

the physician develop a repertoire and knowledge of screening measures. Because

of the complex comorbidity of these disorders, they are often best assessed by

an interdisciplinary team (McKirdy, 1985; Klykylo, 2005). The team’s activities

are usually coordinated by a case manager, of-ten a pediatrician or a child and

adolescent psychiatrist. Often the team includes an audiologist, a

psychologist, medical special-ists including pediatric neurologists and

otorhinolaryngolists, an educational specialist or liaison special educator,

and a speech and language pathologist.

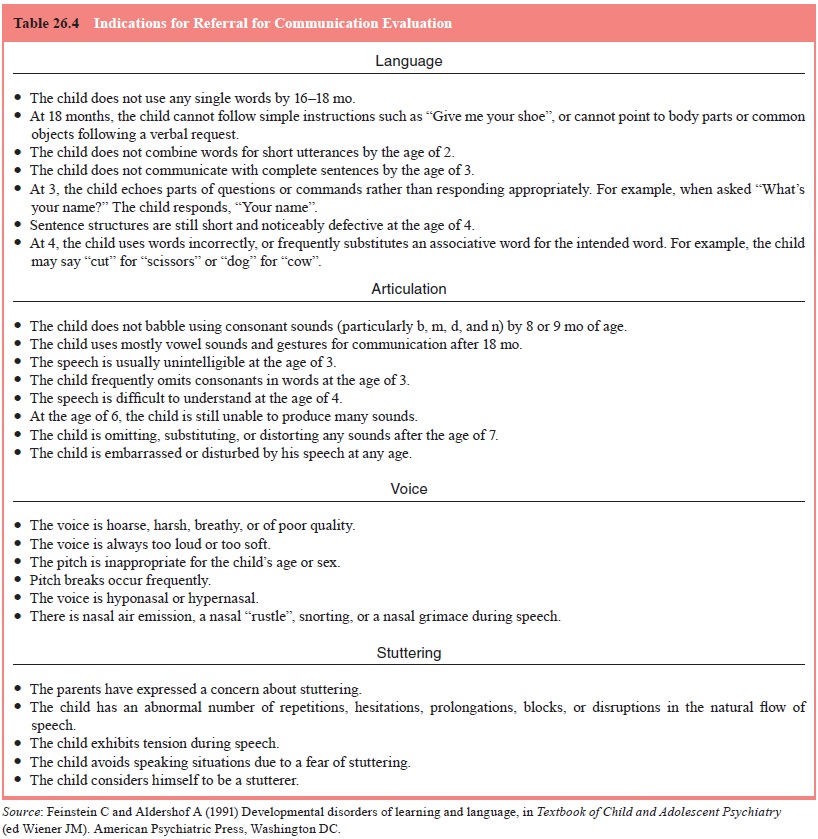

The speech and language pathologist (SLP) has a

gradu-ate professional degree and should be certified by The American

Speech, Language and Hearing Association (ASHA).

The SLP uses a combination of interview techniques, behavioral observations and

standardized instruments to identify Communication Disor-ders, as well as

patterns of communication that are not pathologic. The assessment of an SLP is

usually the definitive measure of the presence or absence of a Communication

Disorder. Families may consult an SLP directly or be referred by other

clinicians. The responsibility of psychiatrists and other professionals in this

process is simple and straightforward: any suspicion of any com-munication

problem in any patient should prompt referral to a qualified SLP. Even when a

disorder appears to be limited and benign, communication evaluation by an SLP

can disclose subtle impairments that could have profound consequences. Table

26.4 lists indication for referral.

Related Topics