Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Learning and Motor Skills Disorders

Childhood Disorders: Communication Disorders

Childhood Disorders: Communication Disorders

Definitions

Psychiatric practice depends upon communication and

language. Language and or learning disorders have been linked in the past, but

in DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) they are regarded as

separate although often associated condi-tions. This section covers: Expressive

Language Disorder, Mixed Receptive-Expressive Language Disorders, Phonological

Disor-der, Stuttering and Communication Disorder NOS. These disor-ders share

many common features, as noted in Table 26.1. They are defined by criteria in

DSM-IV-TR. In all cases a test score or assessment measure alone does not

define these conditions. An individual must also experience social, academic or

occupational difficulties directly related to the condition.

DSM-IV-TR does not consider receptive language

disorders in isolation. Receptive language disorders in children seldom, if

ever, can occur without concurrent (and perhaps resultant) prob-lems with

expression. This is in direct contrast with such entities as Wernicke’s aphasia

in adults, which affect reception alone.

Outside of DSM-IV-TR, the term “phonologic

disorder” may refer to a condition characterized by difficulty in generat-ing

sound combinations, as for example in the case of laryngeal dysfunction.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Prevalences varying from 1 to 13% have been

reported for lan-guage disorders, and numbers as high as 32% for speech

disorders (Baker, 1990). In development of the DSM-IV-TR, researchers found

that

·

Acquired language disorders appear less common than

the developmental types.

·

3–7% of all children were suspected of having a

developmen-tal Expressive Language Disorder.

·

Mixed Expressive – Receptive Language Disorder

appears in up to 3% of school-age children.

·

Phonological Disorder occurs in approximately 2% of

six and seven-year olds, falling to 0.5% by age 17.

·

Stuttering occurs in approximately 1% of children

10 and younger, declining to 0.8% in later adolescence.

·

All of these conditions have a male to female

predominance; that of stuttering is as high as 3 : 1.

Comorbidity

General

Cantwell and Baker (1991) demonstrated that

approximately half of the children with a speech or language disorder have some

other definable Axis I clinical disorder. Similarly, among children with a

psychiatric diagnosis first made, there is a remarkably increased likelihood of

speech and language disorders, which often go un-detected. Beitchman (1985)

found more than four times the preva-lence of psychiatric illness in

kindergartners with communication disorders compared with nondisordered

children. Cantwell and Baker also found that psychiatric illness in their

population was associated with greater severity of communication problems.

Conversely, the presence of communication disorders

may be associated with increased severity of some psychiatric conditions, most

notably the Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Physicians must recognize that these

disorders do not occur in an isolated context

Expressive Language Disorder and Mixed Receptive-expressive Language Disorder

Phonological Disorder and Learning Disorders are

common among children with this disorder. Other neurodevelopmental conditions

are also seen, such as motor delays, coordination disorders and enuresis,

although the rate of association is un-certain. These disorders and the

stresses they create frequently lead to Adjustment Disorders and social

withdrawal. Cantwell and Baker (1991) found that the most common psychiatric

disor-der among children with communication disorders overall was Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), representing 19% of their sample of 600 children

referred for a communi-cation evaluation. Some authors have speculated that

ADHD may be concordant with an entity known as Central Auditory Processing

Disorder (CAPD), which refers to deficits in the pro-cessing of audible

signals, and which can be subsumed under the DSM-IV language disorders. A total

concordance is unlikely, but Riccio et al.

(1994) suggest that 50% of children with CAPD also have ADHD.

Phonologic Disorder

Children with this problem may have clear causal

factors, such as anatomic, neurological, or cognitive disorders, al-though most

do not. They do have a higher prevalence of language disorders, with all their

associated problems, than do normal controls. They appear more likely to have

ADHD, though probably not as commonly as do children with lan-guage disorders.

Children with Phonological Disorders, es-pecially when associated with

stuttering or hyperactivity, are prone to social discrimination and isolation,

with subsequent consequences.

Stuttering

Other communication disorders are more frequently

reported in those with stuttering than in normal controls. Stuttering is

frequently accompanied by many linguistic mechanisms and social maneuvers to

avoid its manifestation, and is often exac-erbated by anxiety or stress.

Persons with stuttering face social discrimination. They have been mocked in

drama and cinema (including cartoons) for centuries, and all too often are

regarded as intellectually impaired.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Genetic Influences

No clear mechanisms of genetic transmission have

been elu-cidated, but a number of instances of family aggregation have been

reported. At least one of these (Gopnik and Crago, 1991) suggested the presence

of a single dominant autosomal gene. Tomblin (1989) reported increased

concordance of language disorders among siblings. An increasing number of

family studies now suggest that these disorders are familial, includ-ing the

Twins Early Development Study (TEDS) in the United Kingdom (Plomin and Dale,

2000). These reports cannot ab-solutely prove any genetic hypothesis but are

provocative and suggest a polygenetic basis.

A genetic basis for stuttering has been proposed

for many years. The Yale Family Study of Stuttering suggested that 15% of first

degree relatives of probands are affected at some time in their lives (Kidd,

1983).

Pathophysiologic influences

Neurophysiological Factors

Communication disorders arise from at least three

interrelated sets of factors: neurophysiologic (including structural),

cogni-tive-perceptual and environmental. However, the great majority of

children with communication disorders exhibit no specific CNS damage, and thus

minimal or subclinical damage has been postulated. The relative frequency of

“soft” neurologic signs and lateral dominance problems in this population

provokes this speculation. However, no clear neurophysiologic mechanisms or

pathology can be correlated with these disorders. Some interest-ing findings

are emerging, including suggested anatomical dif-ferences in the left cerebral

cortex in stuttering, prenatal alcohol exposure and the physical sequelae of

abuse and neglect.

Cognitive and Perceptual Factors

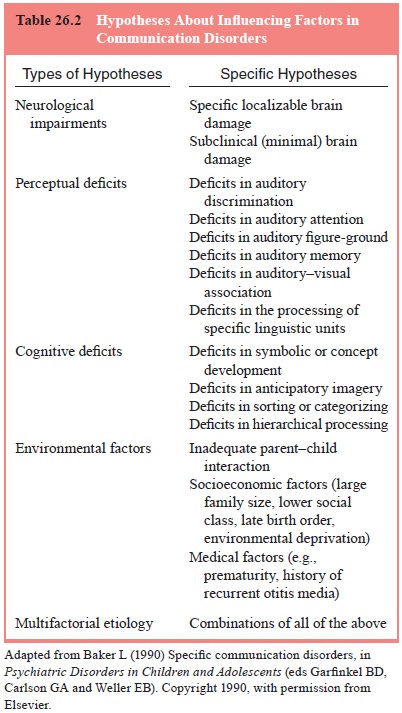

Perceptual hypotheses relate communication

disorders to various deficits in the reception, acquisition, processing,

storage, or recall of different elements of communication. Table 26.2 notes

various perceptual deficits that have been implicated, including auditory

discrimination, attention, memory and visual

association. More purely cognitive hypotheses have also been proposed,

involving deficits in symbolization, categorizing, hierarchical processing and

related areas. Some authors (Friel-Patti, 1992; Helmuth, 2001) propose that

there are certain language-specific cognitive deficits. The special

phenomenology of stuttering suggests the possibility of dyssynchrony between

phonation and articulation, as reported by Perkins (2001).

Environmental Factors

This category refers both to the psychosocial

environment of the child and to general medical factors such as perinatal

complica-tions or recurrent otitis media.

The relationship of socioeconomic status to the

occurrence of communication disorders is uncertain. Variables such as class,

family size, income and birth order all clearly affect the amount of verbal

interaction children receive and have been implicated. The association between

the exacerbation of stuttering and stress is well known, although work in this

area has frequently con-founded predisposing, triggering and maintaining

factors.

Review of these influences reveals a considerable

amount of overlap, and clinical observation seldom if ever suggests a uni-tary

causality of Communication Disorders in real patients.

Related Topics