Chapter: Cryptography and Network Security Principles and Practice : Legal And Ethical Aspects

Cybercrime and Computer Crime

CYBERCRIME

AND COMPUTER CRIME

The bulk of this book examines technical approaches to the detection,

prevention, and recovery from computer and network attacks. One other tool is

the deterrent factor of law enforcement.

Many types of computer attacks can be considered

crimes and, as such, carry

criminal sanctions. This

section begins with a classification of types of computer crime

and then looks at some of the unique law-enforcement

challenges of dealing

with computer crime.

Types of Computer

Crime

Computer crime, or cybercrime, is a term used broadly

to describe criminal

activity in which computers or computer networks

are a tool, a target,

or a place of criminal activity.1 These categories are not exclusive, and many activities can be character- ized as falling in one or more categories. The term cybercrime

has a connotation of the use of networks specifically, whereas computer crime may

or may not involve networks.

The U.S. Department of Justice [DOJ00]

categorizes computer crime based on the role that the computer

plays in the criminal activity, as follows:

•

Computers as targets: This form of crime targets a computer system, to acquire information stored on that computer system,

to control the target sys- tem

without authorization or payment (theft of service), or to alter the integrity of data or interfere with the

availability of the computer or server. Using the terminology of Chapter 1, this form of crime involves an attack on

data integrity, system

integrity, data confidentiality, privacy, or availability.

Computers as storage devices: Computers can be used to further unlawful

activity by using a computer or a computer device as a passive storage medium. For example,

the computer can be used to store

stolen password lists, credit card or calling

card numbers, proprietary corporate information, porno- graphic image files, or “warez” (pirated commercial software).

•

Computers as communications

tools: Many of the crimes falling

within this category are

simply traditional crimes that are committed online. Examples include the

illegal sale of prescription drugs, controlled substances, alcohol, and guns;

fraud; gambling; and

child pornography.

A more specific list of crimes, shown in Table 23.1, is defined in the interna- tional Convention on Cybercrime.2 This

is a useful list because it represents an

international consensus on what constitutes computer crime, or

cybercrime, and what crimes

are considered important.

Yet another categorization is used in the CERT 2006 annual E-crime Survey, the results of which are shown in Table 23.2. The figures in the second column indicate the percentage of respondents who report at least one incident in the corresponding row category. Entries in the remaining three columns indicate the percentage of respondents who reported a given source for an attack.3

Law Enforcement Challenges

The deterrent effect

of law enforcement on computer

and network attacks

correlates with the success

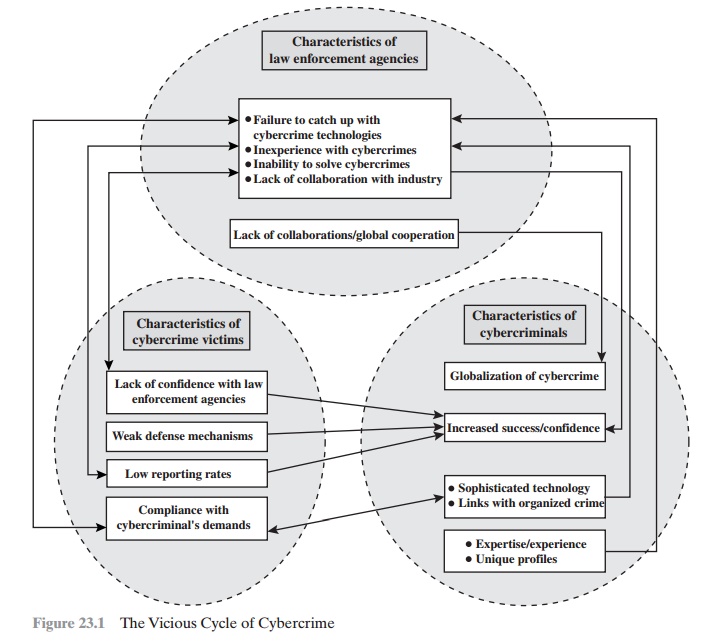

rate of criminal arrest and prosecution. The nature of cybercrime is such that consistent success is extraordinarily difficult. To see this, consider what [KSHE06] refers to as the vicious

cycle of cybercrime, involving law enforcement agencies, cybercriminals,

and cybercrime victims (Figure 23.1).

For law enforcement agencies, cybercrime presents

some unique difficulties. Proper investigation requires a fairly

sophisticated grasp of the technology.

Although some agencies, particularly larger agencies, are catching up in this

area, many jurisdictions lack investigators knowledgeable and experienced in

dealing with this kind of crime.

Lack of resources represents another

handicap. Some cyber- crime investigations require considerable computer processing power,

communica- tions capacity,

and storage capacity, which may be beyond the budget of individual

jurisdictions. The global nature

of cybercrime is an additional obstacle: Many crimes will involve perpetrators who are

remote from the target system, in another juris- diction or even another country.

A lack of collaboration and cooperation with remote law enforcement agencies can greatly hinder an

investigation. Initiatives such as the international

Convention on Cybercrime are a promising

sign. The Convention at least introduces a common terminology for crimes and a framework for harmonizing laws globally.

Table 23.1 Cybercrimes Cited in the Convention on Cybercrime

Article 2 Illegal access

The access to the whole or any part of a computer system without right.

Article 3 Illegal interception

The interception without right, made by technical means, of non-public transmissions of computer data to, from or within a computer system, including electromagnetic emissions from a computer system carrying such computer data.

Article 4 Data interference

The damaging, deletion, deterioration, alteration or suppression of computer data without right.

Article 5 System interference

The serious hindering without right of the functioning of a computer system by inputting, transmitting, damaging, deleting, deteriorating, altering or suppressing computer data.

Article 6 Misuse of devices

a. The production, sale, procurement for use, import, distribution or otherwise making available of:

i. A device, including a computer program, designed or adapted primarily for the purpose of commit- ting any of the offences established in accordance with the above Articles 2 through 5;

ii. A computer password, access code, or similar data by which the whole or any part of a computer system is capable of being accessed, with intent that it be used for the purpose of committing any of the offences established in the above Articles 2 through 5; and

b. The possession of an item referred to in paragraphs a.i or ii above, with intent that it be used for the purpose of committing any of the offences established in the above Articles 2 through 5. A Party may require by law that a number of such items be possessed before criminal liability attaches.

Article 7 Computer-related forgery

The input, alteration, deletion, or suppression of computer data, resulting in inauthentic data with the intent that it be considered or acted upon for legal purposes as if it were authentic, regardless whether or not the data is directly readable and intelligible.

Article 8 Computer-related fraud

The causing of a loss of property to another person by:

a. Any input, alteration, deletion or suppression of computer data;

b. Any interference with the functioning of a computer system, with fraudulent or dishonest intent of procuring, without right, an economic benefit for oneself or for another person.

Article 9 Offenses related to child pornography

a. Producing child pornography for the purpose of its distribution through a computer system;

b. Offering or making available child pornography through a computer system;

c. Distributing or transmitting child pornography through a computer system;

d. Procuring child pornography through a computer system for oneself or for another person;

e. Possessing child pornography in a computer system or on a computer-data storage medium.

Article 10 Infringements of copyright and related rights Article 11 Attempt and aiding or abetting

Aiding or abetting the commission of any of the offences established in accordance with the above

Articles 2 through

10 of the present Convention with intent that such offence

be committed. An attempt

to commit any of the offences established in accordance with Articles 3 through 5, 7, 8, and 9.1.a and c. of

this Convention.

Table 23.2 CERT

2006 E-Crime Watch Survey Results

The relative lack of success in bringing cybercriminals

to justice has led to an increase

in their numbers, boldness, and

the global scale of their operations. It is difficult

to profile cybercriminals in the way that

is often done with other types

of repeat offenders. The cybercriminal

tends to be young and very computer-savvy, but the range of

behavioral characteristics is wide. Further, there exist no cybercriminal

databases that can point

investigators to likely

suspects.

The success of cybercriminals, and the relative lack of

success of law enforce- ment, influence the behavior

of cybercrime

victims. As with

law enforcement, many organizations that may be the target of attack have

not invested sufficiently in technical, physical, and

human-factor resources to prevent

attacks. Reporting rates tend to

be low because of a lack of confidence in law enforcement, a concern about corporate

reputation, and a concern

about civil liability. The low reporting

rates and the reluctance to work with law enforcement on

the part of victims feeds into the handicaps

under which law enforcement works,

completing the vicious cycle.

Working With Law Enforcement

Executive management and security administrators need to look upon law enforce-

ment as another resource and tool, alongside technical, physical, and human-factor

resources. The successful use of law enforcement depends much more on people

skills than technical skills. Management needs to understand the criminal investiga- tion process, the inputs

that investigators need,

and the ways in which

the victim can contribute positively to the investigation.

Related Topics