Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : Common Uncomplicated Specimens

Common Uncomplicated Specimens : Surgical Pathology Dissection

Common Uncomplicated Specimens

The

dissection of tonsils, adenoids, hernia sacs, intervertebral discs, and

amputations for gan-grene are fairly straightforward, yet a brief discussion of

the appropriate handling of these specimens is important for two reasons.

First, because these specimens are so frequently en-countered, even small

mistakes in technique can be magnified over the course of handling numer-ous

specimens. By getting it right the first time, you can avoid developing bad

habits that are perpetuated with subsequent dissections. Second, mundane

specimens are particularly suscepti-ble to cursory and inattentive

examinations. As is true for novel and complex specimens, the pro-sector should

carefully examine the specimen and tailor a dissection that is attuned to the

clini-cal context.

Tonsils and Adenoids

The term

tonsils usually refers to the

palatine ton-sils. These are located laterally on each side of the oral cavity

as it communicates with the oro-pharynx. The term adenoids refers to the pharyn-geal tonsils. These are located along

the roof of the nasal cavity as it communicates with the naso-pharynx. Even

when these two structures are re-ceived together in the same specimen

container, they can easily be distinguished by their gross appearance. The

palatine tonsils are oval-shaped nodules of tissue. They are longer vertically

than they are horizontally. Their attached (i.e., lateral) surface is covered

by a thick fibrous capsule with adherent soft tissues, while their free (i.e.,

medial) surface is covered by a tan, glistening mucosa and is somewhat

cerebriform, which is due toa longitudinal cleft and stellate crypt openings.

The adenoids, on the other hand, tend to be flat and are frequently fragmented

when removed. Their free (mucosal) surfaces are disrupted by deep longitudinal

clefts that extend into the un-derlying lymphoid tissue.

The

palatine tonsils are usually removed from both sides of the oropharynx. Subtle

changes in the size, shape, and consistency of the ton-sils can be appreciated

by comparing the two tonsils. For example, enlargement that is due to an

infiltrative process may best be appre-ciated when the enlarged tonsil is

compared to the normal tonsil from the opposite side. After the tonsils and

adenoids are identified, they should be separately measured and de-scribed.

Look for exophytic masses, ulcerations, bulky enlargement, and any other gross

abnor-malities. Bivalve the tonsils and adenoids along the long axis of each,

and carefully inspect the cut surface for masses, abscess formation, or other

lesions.

Tonsils

and adenoids do not always need to be submitted for histologic evaluation. The

deci-sion to sample these specimens depends on the patient’s clinical history

and the gross findings. From our own experience, we have found that these

specimens should be sampled for

histologic evaluation if they meet any of the criteria listed below:

1. The age

of the patient is greater than 10 or less than 3 years.

2. The

tonsils or adenoids are grossly ab-normal.

3. The

tonsils or adenoids are greater than 3 cm.

4. There is

a size disparity between the two tonsils.

5. Histologic

evaluation is requested by the clini-cian or is indicated by the patient’s

clinical history.

If any

one of the above criteria is met, the tonsils and adenoids should be

appropriately sampled for histologic evaluation. One or two represen-tative

sections of the tonsils and adenoids are generally sufficient, but certain

conditions may require special processing or more extensive sec-tioning. For

example, diffusely enlarged tonsils or adenoids with architectural effacement

may suggest involvement by a lymphoproliferative disorder, and these should be

processed like a lymph node involved by a lymphoma (see Chap-ter 41). Sometimes

the tonsils are removed in an attempt to find an ‘‘occult’’ primary neoplasm in

a patient presenting with metastatic carcinoma to cervical lymph nodes. In this

situation, the tonsils should be serially sectioned and submit-ted in their

entirety for histologic evaluation. If the tonsils or adenoids do not meet any

of the above criteria, they do not need to be sampled for histologic

evaluation. After completing your gross description, place the specimen in

formalin and store it for at least 2 weeks.

Hernia Sacs

Hernia

sacs are pouches of peritoneum enclosing a hernia. Grossly and microscopically,

these are unimpressive specimens. They consist of vari-able amounts of fat,

fibroconnective tissue, and a mesothelium-lined peritoneum. Nonetheless, even

hernia sacs attest to the dictum that unex-pected but important pathologic

findings can be discovered in the most mundane of specimens. Indeed, a wide

range of pathologic findings have been documented in routinely resected hernia

sacs, ranging from endometriosis to malignant mesothelioma.

Measure

and describe the sac, taking note of any areas that appear hemorrhagic or

discolored. Palpate the specimen, and document the contents of the hernia sac

and whether any nodules are present. Small specimens do not require addi-tional

sectioning. Larger tissue fragments should be serially sectioned. Document the

gross appear-ance of the cut sections. Standards for submitting grossly normal

hernia sacs for histologic exami-nation vary from institution to institution.

In the current era of cost containment, some centershave eliminated the routine

histologic examina-tion of grossly normal pediatric hernia sacs. Nonetheless, all

grossly abnormal hernia sacs, all hernia sacs excised from adults, and all

hernia sacs from patients whose clinical history indicates a possible

histology-based diagnosis should be submitted for histologic evaluation. Most

hernia sacs can be entirely submitted in a single tissue cassette for

histologic evaluation. For larger speci-mens, a single cassette with sections

representing all components of the specimen is generally suf-ficient. More

extensive sampling may be neces-sary when focal lesions are identified or when

indicated by the patient’s clinical history.

Intervertebral Disk Material

Intervertebral

disks typically consist of multiple irregular fragments of fibrous tissue,

cartilage, and bone in variable proportions. These frag-ments are small and generally

do not require sectioning. Nonetheless, the prosector’s role in handling these

is not inconsequential. The appro-priate sampling and processing of these

speci-mens largely depends on the prosector’s skill at recognizing the various

components that are present.

Begin by

measuring the specimen. This can be done most efficiently by measuring the

aggre-gate dimensions of the specimen (not the dimen-sions of each individual

piece). Describe the type and appearance of the tissue received. Separate the

bone from the soft tissue fragments, and decalcify the pieces of bone so that

they can be sectioned by the histology laboratory (see Chap-ter 2). Keep in

mind that these small bone frag-ments do not require nearly as much time to

decalcify as sections from large bone resections. As is true for tonsils,

adenoids, and hernia sacs, some centers have eliminated histologic exami-nation

of disk tissue specimens after routine cervical and lumbar decompression.

Nonethe-less, routine disk tissue is submitted for histolo-gic examination at

most centers, and the tissues must be submitted when clinically indicated.

After the bone has been separated, submit the soft tissues for histologic

evaluation. Again, if all of the tissue does not easily fit into a single

tissue cassette, submit fragments that are rep-resentative of the specimen as a

whole. Some-times the patient’s clinical history may indicatemore extensive

sampling, as when metastatic car-cinoma is suspected clinically.

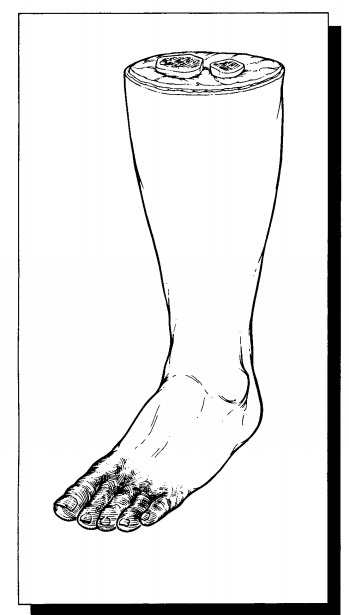

Amputations for Gangrene

Admittedly,

most amputation specimens are nei-ther small nor anatomically simple. On the

other hand, the dissection of amputations for gangrene is straightforward and

need not entail an inordi-nate amount of time and effort. The dissection of

these specimens, whether a resection of a digit or an entire limb, should focus

on two key questions: What are the nature and extent of the lesion (e.g.,

ulceration and gangrene)? What is the underly-ing pathologic process (e.g.,

vascular occlusion)? As for all specimens, the patient’s clinical history

should be clarified before the dissection of an amputation specimen is begun.

Clinical and ra-diographic findings may direct the dissection to the most

relevant areas of the specimen.

First,

measure the overall dimensions of the specimen. Make liberal use of anatomic

land-marks (e.g., tibial tubercle, lateral tibial malleo-lus) when measuring

the specimen and describing the location of any lesions. Next, examine the four

components of the specimen—the skin, soft tissues, bone, and vasculature. Begin

with the skin. Look for loss of hair, skin discoloration, and frank ulceration.

Note the location of these findings. Next, evaluate the soft tissues. Section

through any ulcers to determine the depth of the ulcer. Do the surrounding soft

tissuesappear necrotic? Also note whether the soft tis-sues at the surgical

margin appear viable. The bone underlying areas of ulceration and necrosis is

most likely to reveal pertinent pathology. Spe-cifically, section through the

deepest area of any ulcer, and determine if the underlying bone is grossly

involved by the inflammatory process. Fi-nally, evaluate the vasculature. For

amputations of the lower limbs, occlusive vascular disease can usually be

documented by performing a limited dissection of the anterior and posterior

tibial ar-teries. These can be located by sectioning deeply into the anterior

and posterior compartments of the calf. A deep transverse incision at midcalf

can usually accomplish this. When a complete dissec-tion of a particular

vascular tree is indicated, an anatomy text outlining the distribution of the

blood supply should be consulted.![]()

Sections

should be taken to demonstrate is-chemic changes in the skin, necrosis of the

soft tissue, inflammation in the underlying bone, oc-clusive disease of the

vascular tree, and viability of the soft tissues at the surgical margin. When

sampling the ulcer, include the adjacent epider-mis and the underlying

subcutaneous tissues. If the zone of ulceration and necrosis appears to extend

to the bone, submit a section of the bone immediately underlying the ulcer.

Submit cross sections of the major arteries, selectively sam-pling those

regions where the lumen is most stenotic. Finally, submit a transverse section

of the neurovascular bundle at the resection margin, along with some skin and

soft tissue from this region.

Related Topics