Chapter: Medical Physiology: Cardiac Failure

Chronic Stage of Failure-Fluid Retention Helps to Compensate Cardiac Output

Chronic Stage of Failure-Fluid Retention Helps to Compensate Cardiac Output

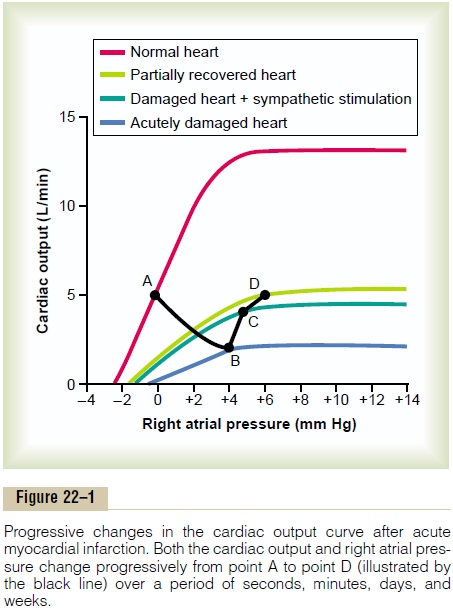

After the first few minutes of an acute heart attack, a prolonged semi-chronic state begins, characterized mainly by two events: (1) retention of fluid by the kidneys and (2) varying degrees of recovery of the heart itself over a period of weeks to months, as illus-trated by the light green curve in Figure 22–1;.

Renal Retention of Fluid and Increase in Blood Volume Occur for Hours to Days

A low cardiac output has a profound effect on renal function, sometimes causing anuria when the cardiac output falls to one-half to two-thirds normal. In general, the urine output remains reduced below normal as long as the cardiac output and arterial pres-sure remain significantly less than normal, and urine output usually does not return all the way to normal after an acute heart attack until the cardiac output and arterial pressure rise either all the way back to normal or almost to normal.

Moderate Fluid Retention in Cardiac Failure Can Be Beneficial.

Many cardiologists formerly considered fluid retention always to have a detrimental effect in cardiac failure. But it is now known that a moderate increase in body fluid and blood volume is an important factor in helping to compensate for the diminished pumping ability of the heart by increasing the venous return.

The increased blood volume increases venous return in two ways: First, it increases the mean systemic filling pressure, whichincreases the pressure gradient forcausing venous flow of blood toward the heart. Second,it distends the veins, which reduces the venous resist-ance and allows even more ease of flow of blood to theheart.

If the heart is not too greatly damaged, this increased venous return can often fully compensate for the heart’s diminished pumping ability—enough in fact that even when the heart’s pumping ability is reduced to as low as 40 to 50 per cent of normal, the increased venous return can often cause an entirely normal cardiac output as long as the person remains in a quiet resting state.

When the heart’s pumping capability is reduced still more, blood flow to the kidneys finally becomes too low for the kidneys to excrete enough salt and water to equal salt and water intake. Therefore, fluid retention begins and continues indefinitely, unless major therapeutic procedures are used to prevent this. Furthermore, because the heart is already pumping at its maximum pumping capacity, this excess fluid nolonger has a beneficial effect on the circulation. Instead,severe edema develops throughout the body, which can be very detrimental in itself and can lead to death.

Detrimental Effects of Excess Fluid Retention in Severe Cardiac Failure. In contrast to the beneficial effects of moder-ate fluid retention in cardiac failure, in severe failure extreme excesses of fluid can have serious physiologi-cal consequences. They include (1) overstretching of the heart, thus weakening the heart still more; (2) filtration of fluid into the lungs, causing pulmonary edema and consequent deoxygenation of the blood; and (3) development of extensive edema in most parts of the body.

Recovery of the Myocardium After Myocardial Infarction

After a heart becomes suddenly damaged as a result of myocardial infarction, the natural reparative processes of the body begin immediately to help restore normal cardiac function. For instance, a new collateral blood supply begins to penetrate the periph-eral portions of the infarcted area of the heart, often causing much of the heart muscle in the fringe areas to become functional again. Also, the undamaged portion of the heart musculature hypertrophies, in this way offsetting much of the cardiac damage.

The degree of recovery depends on the type of cardiac damage, and it varies from no recovery to almost complete recovery. After acute myocardial infarction, the heart ordinarily recovers rapidly during the first few days and weeks and achieves most of its final state of recovery within 5 to 7 weeks, although mild degrees of additional recovery can continue for months.

The Cardiac Output Curve After Partial Recovery. Figure 22–1shows function of the partially recovered heart a week or so after acute myocardial infarction. By this time, considerable fluid has been retained in the body and the tendency for venous return has increased markedly as well; therefore, the right atrial pressure has risen even more. As a result, the state of the cir-culation is now changed from point C to point D, which shows a normal cardiac output of 5 L/min but right atrial pressure increased to 6 mm Hg.

Because the cardiac output has returned to normal, renal output of fluid also returns to normal, and no further fluid retention occurs, except that the retentionof fluid that has already occurred continues to maintain moderate excesses of fluid. Therefore, except for thehigh right atrial pressure represented by point D in this figure, the person now has essentially normal car-diovascular dynamics as long as he or she remains atrest.

If the heart recovers to a significant extent and if adequate fluid volume has been retained, the sympa- thetic stimulation gradually abates toward normal for the following reasons: The partial recovery of the heart can elevate the cardiac output curve the same as sympathetic stimulation can. Therefore, as the heart recovers even slightly, the fast pulse rate, cold skin, and pallor resulting from sympathetic stimulation in the acute stage of cardiac failure gradually disappear.

Related Topics