Chapter: Medicine and surgery: Breast disorders

Breast cancer

Breast cancer

Definition

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy of females in the developed world.

Incidence

Approximately 2/1000 p.a. 1 in 12 women (lifetime risk); 20% of all cancers.

Age

Adults. Peak 50–60 years

Sex

99% in females, and 1% in males.

Geography

More common in North America (1 in 10) and Northern Europe. It is associated with higher social class. Migrants from low-risk to high-risk areas have increased incidence.

Aetiology

In most cases it appears to be multifactorial with a strong environmental influence.

· Exposure to oestrogen is important. Increased risk with early menarche, late menopause, nulliparity, low parity and late first pregnancy.

· Family history of breast cancer.

· History of previous breast disease especially atypical hyperplasia.

· Current evidence indicates a slightly increased risk from the oral contraceptive pill from 2/1000 to 3/1000.

· Hormone replacement therapy postmenopause increases risk.

· Dietary factors (obesity and high alcohol intake) have been implicated.

· Genetic: Two genes have been identified, autosomal dominant with variable penetrance:

1. BRCA-1 on the long arm of chromosome 17 accounts for <5% of cases of breast cancer, but possessing the gene gives an 80% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer and increased risk of ovarian cancer.

2. BRCA-2 on chromosome 13 is less common. There is increased breast and prostate cancer in the family. This gene is particularly associated with male breast cancer.

3. Mutations in the p53 tumour suppressor gene are also associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer.

Pathophysiology

Most tumours of the breast are adenocarcinomas, which develop from the epithelial cells of the terminal duct/lobular unit. They may either take a lobular or ductal histological appearance on the basis of cell differentiation and architecture. Lobular and ductal carcinoma behave differently in terms of spread.

1. If the atypical cells have not penetrated the basement membrane, it is termed carcinoma in situ. These tumours form approximately 20% of carcinomas of the breast.

Ductal carcinoma in situ is now classified according to histological characteristics (including nuclear grade and the presence or absence of necrosis), which helps to predict the potential of the lesion to recur within the breast or to progress to invasive breast cancer. This grading helps to guide management allowing conservative surgery with or without radiotherapy, whereas previously all patients underwent mastectomy.

Lobular carcinoma in situ is not palpable and has no characteristic findings on mammography. It is identified as a coexistent finding during micro-scopic examination of breast tissue samples taken for other reasons (e.g. fibrocystic change). Lobular carcinoma in situ is thought to represent a non-obligate precursor of invasive carcinoma, which may occur at sites other than that of the original biopsy. Management is by close surveillance.

2. Once cells invade the basement membrane, they spread locally and may metastasise and are said to be ‘infiltrating’ or invasive carcinoma of the breast:

Invasive ductal carcinoma is the most common primary malignant tumour (approximately 80%).

Invasive lobular breast cancer accounts for approximately 10%.

Lobular carcinoma is not a feature in males.

Clinical features

The woman (or rarely, a man) usually presents with a painless lump in the breast or after routine mammo-graphic screening. It most often occurs in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Occasionally the lump aches or has an unpleasant prickling sensation. Signs of malignancy on examination include the following:

· A firm non-tender irregular lump with illdefined edges, which is tethered or fixed to skin or underlying muscle.

· Palpable lymph nodes in the axilla, hard in texture, which may be discrete or matted together or to over-lying skin or subcutaneous tissue.

· Arm oedema is a late sign, because of involvement of axillary lymph nodes.

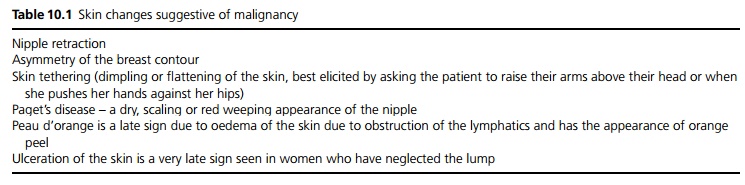

· Skin changes suggestive of malignancy are given in Table 10.1.

Some patients present with metastatic disease and a hidden primary. Back pain due to vertebral collapse, short-ness of breath or pleuritic chest pain due to spread to the lungs and jaundice due to liver involvement are signs of disseminated disease. Weight loss and malaise are also late symptoms.

Macroscopy/microscopy

The macroscopy of invasive tumours is largely determined by the stromal reaction around the cells. Most tumours excite a lot of reaction forming gritty nodules. If they excite little reaction, they are soft and fleshy.

Invasive ductal carcinoma: The majority of these have no special histological features, reflecting their lack of differentiation. Approximately 50% of invasive tumours are pure ductal carcinoma, a further 25% have ductal mixed with another type (usually lobular).

Invasive lobular carcinoma: Characteristically consists of small, bland, homogeneous cells that invade the stroma in ‘Indian file’ pattern. It is often multifocal and may be bilateral in up to 15% of cases.

Other forms of invasive breast cancer exist, which have certain well-differentiated features and so are described as medullary, papillary, mucinous or tubular. These (particularly the tubular and mucinous types) have a better prognosis than invasive ductal or lobular carcinoma.

Tumours can be stained for oestrogen receptors, which affects response to treatment.

In Paget’s disease of the nipple, the skin of the nipple and areola is reddened and thickened, mimicking eczema. It is a form of ductal carcinoma arising from the large excretory ducts. The epidermidis is infiltrated by large pale vacuolated epithelial cells, and there is almost always an in situ or invasive ductal carcinoma in the underlying breast tissue.

Complications

Lymphatic and haematogenous spread. Ninety to ninety-five per cent of the breast drains to the axillary nodes, the remainder drains to the internal mammary nodes. Haematogenous spread may occur before or after lymphatic spread. The most common organs affected are bone, liver, lung and pleura, brain, ovaries (Krukenberg tumour is an enlarged ovary due to 2˚ tumour cells) and adrenal glands.

Investigation

Investigation of a breast lump involves a triple assessment:

1. Clinical history and examination.

2. Imaging using mammography or ultrasound in younger women.

3. Breast tissue sampling using needle core biopsy or fine needle aspiration. This also allows staining for hormone receptors, which guides management.

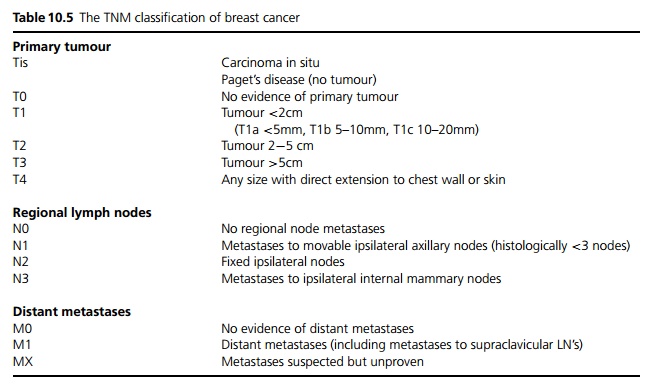

If a malignancy is confirmed patients may undergo a chest X-ray, full blood count and liver function tests for staging. Isotope bone scan, liver ultrasound and CT brain scan may also be required if clinically indicated (see Table 10.5).

Management

Early or operable breast cancer (Up to T2, N1, M0 breast cancer with or without mobile lymph nodes on the same side and no evidence of metastases) is potentially curable. The decision between differing combinations of therapy is complex and involves factors such as breast size, patient choice, multifocality, tumour site, tumour type, recurrence of previously treated tumours and where ra-diotherapy is contraindicated.

Local treatment:

Breast conservation surgery involves a wide local excision of the lesion. Conservative breast surgery with radiotherapy has been shown to be as effective as mastectomy in terms of long-term survival.

Simple mastectomy describes the removal of breast

parenchyma including nipple and areolar.

Lymph node treatment:

Assessment of the presence of spread to the lymph nodes may be achieved by axillary lymph node sampling or dissection (the latter is also therapeutic). Sentinel node biopsy involves sampling the first 2–4 axillary lymph nodes draining the breast. These sentinel nodes may be identified by intraoperative injection of a tracer around the tumour site. If the sentinel nodes are free from metastases, this indicates that there has been no spread to the remainder of the axilla (5% false negative rate) and no further treatment is required.

If axillary node sampling or sentinel biopsy have demonstrated nodal metastases, axillary clearance or radiotherapy is required.

Locally advanced disease: Patients are treated with preoperative systemic therapy and then if they become operable they undergo surgery. In more than 65% of women, the tumour shrinks by more than 50%, which makes it more likely that the whole tumour is excised at surgery and in some patients allows breast conservation. This form of treatment may also be used in patients with stage T2 tumours to facilitate breast-conserving surgery. Radiotherapy and further systemic therapy may be used with or without surgery.

Metastatic breast cancer: The aim of treatment is palliation of symptoms and improving quality of life as currently most of these patients die from breast cancer. Treatments include radiotherapy, systemic treatment and surgery to debulk the primary tumour, which may be ulcerating through the skin and alleviate symptoms such as bone pain, pleural and pericardial effusions.

Systemic therapy: The choice of which therapies are used depends on whether patients are pre- or post-menopausal, if they have oestrogen-receptor positive disease, their risk of recurrence and the stage of their disease.

Hormonal therapy should be used in all patients with oestrogen-receptor positive tumours. Premenopausal women are given LHRH analogues and tamoxifen. Postmenopausal women receive either tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor, which reduces the peripheral conversion of androgens to oestrogen. Aromatase inhibitors appear to be as effective as tamoxifen with fewer side effects.

Adjuvant combination chemotherapy has been shown to be more effective than a single agent. Most regimens are administered 3–4 weekly for 4–6 cycles. A new class of chemotherapeutic agents called taxanes has resulted from yew treederived products, e.g. paclitaxel and docetaxel.

Recent advances have occurred in monoclonal antibodies directed against HER2, which is overexpressed in 15–20% of breast cancers. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) has been shown to prolong survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2.

Prognosis

The important prognostic indicator is the TNM staging (see Table 10.5):

T: Increasing size of tumour indicates worse prognosis. N: Nodal involvement reduces 5-year survival from 80

to 60%.

M: Haematogenous spread has a much poorer prognosis (5-year survival is only 10%). Average survival is 14–18 months with chemotherapy.

Well-differentiated cells also improve the prognosis.

Related Topics