Chapter: XML and Web Services : The Semantic Web : RDF for Information Owners

Basics of the Resource Description Framework

Basics

of the Resource Description Framework

We often hear that XML tags

add meaning to documents. And this is true, but it’s meaning that only humans

can intuit. For example, given the XML markup

<person name=”Jane”>

<sells product=”books”/> </person>

a human might use the

intuitive tag names and attribute name/value pairs to infer that “Jane sells

books” (among other things that people may do), but this is a leap of faith

that a machine cannot make. True, the content models in a DTD or schema can

enforce that sells nests within person, but it does not tell us anything about why the nesting takes

place.

Similarly, given the

preceding markup, an XSLT style sheet could transform it into the following

string:

“Jane sells

books”

However, to the computer,

this is just a string like many other strings. In the end, the computer has no

power to do anything with the string other than display it. In particular, it

can’t make any logical connection between the string “Jane sells this book” and

the string “My human wants to buy this book” and make the purchase. Such

strings have meaning only to humans.

What we need is to go beyond

the notion of a content model to a “meaning model,” which is what the RDF data

model provides. Listing 23.1 gives us the markup for the RDF statement that has

the meaning “Jane sells books,” where “Jane” is in RDF’s sub-ject position,

“sells” is in the predicate position, and “books” is in the object position. In

this way, we use markup technology to tell the computer where the meaning is.

Note that “[Jane]” and “[books]” are URIs, and sells is a name in the “[my]” namespace; you’ll see why

later.

LISTING 23.1 A Simple

Statement in RDF

<rdf:Description about=”[Jane]”

xmlns:my=”[my]”> <my:sells

rdf:resource=”[books]”/>

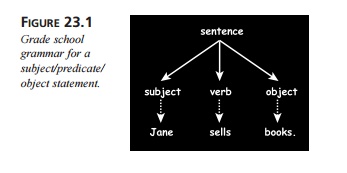

The idea here is just as

simple as when a teacher draws a subject/verb/object diagram on the chalkboard

in grade school, as shown in Figure 23.1. If you want your sentence to mean

anything, you have to put the words in the right order—and you and your

listener have to know what the order is.

What the teacher’s syntax

production does for students, in chalk, the RDF data model does for machines,

in bits and bytes. Now let’s look a bit more deeply into the three words that comprise

RDF: resource, description, and framework.

Why resource? A resource is anything that has identity

(Jane, for example). How do resources get identity? Through being identified by

Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs). Therefore, that which has identity is a

resource, and that which is a resource has identity!

If you look back to Listing

23.1, you will see that both the subject and the object of the RDF statement

are resources, because they are identified by URIs.

Not all resources (for

example, Jane) are retrievable across a network. A URI can iden-tify a Web

page, of course, but also a printed book, a government agency, a human being,

or an abstract concept.

Why description? A description is really just a container;

it is a bucket for one or more statements. This idea, too, is pretty much

straight from the grade school dictionary. If I ask Jane’s friend (or maybe

even her computer) for a description of Jane, I expect to get back a number of

statements, one of which might be that “Jane sells books.”

Why a framework? Natural

languages such as English and Esperanto permit speakers to generate infinite

numbers of sentences, to invent new words, and to give new meanings to old

words, all based on a reasonably small set of rules. These rules comprise the framework

of the language. In the same way, RDF sets rules that will enable humans and

machines to make and understand infinite numbers of statements whose subjects

and objects are resources.

Related Topics