Chapter: Analysis and Design of Algorithm : Backtracking

Backtracking Algorithms

BACKTRACKING

Many

problems are difficult to solve algorithmically. Backtracking makes it possible

to solve at least some large instances of difficult combinatorial problems.

GENERAL METHOD

The

principal idea is to construct solutions one component at a time and evaluate

such partially constructed candidates as follows.

If a

partially constructed solution can be developed further without violating the

problem‘s

constraints, it is done by taking the first remaining legitimate option for the

next component.

If there

is no legitimate option for the next component, no alternatives for any

remaining

component need to be considered. In this case, the algorithm backtracks to

replace the last component of the partially constructed solution with its next

option.

STATE-SPACE TREE

It is

convenient to implement this kind of processing by constructing a tree of

choices being made, called the state-space

tree. Its root represents an initial state before the search for a solution

begins. The nodes of the first level in the tree represent the choices made for

the first component of a solution; the nodes of the second level represent the

choices for the second component, and so on.

A node in

a state-space tree is said to be promising

if it corresponds to a partially constructed solution that may still lead to a

complete solution; otherwise, it is called nonpromising.

Leaves

represent either nonpromising dead ends

or complete solutions found by the

algorithm.

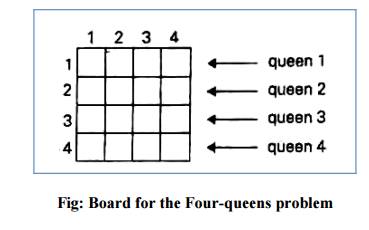

N-QUEENS PROBLEM

The

problem is to place it queens on an n-by-n chessboard so that no two queens

attack each other by being in the same row or in the same column or on the same

diagonal. For n = 1, the problem has a trivial solution, and it is easy to see

that there is no solution for n = 2 and n =3. So let us consider the

four-queens problem and solve it by the backtracking technique. Since each of

the four queens has to be placed in its own row, all we need to do is to assign

a column for each queen on the board presented in the following figure.

Steps to be followed

We start with the empty board and then place queen 1 in the first possible position of its row, which is in column 1 of row 1.

Then we place queen 2, after trying unsuccessfully columns 1 and 2, in the first acceptable position for it, which is square (2,3), the square in row 2 and column 3. This proves to be a dead end because there i no acceptable position for queen 3. So, the algorithm backtracks and puts queen 2 in the next possible position at (2,4).

Then queen 3 is placed at (3,2), which proves to be another dead end.

The algorithm then backtracks all the way to queen 1 and moves it to (1,2). Queen 2 then goes to (2,4), queen 3 to (3,1), and queen 4 to (4,3), which is a solution to the problem.

(x denotes an unsuccessful attempt to place a queen in the indicated column. The numbers above the nodes indicate the order in which the nodes are generated)

If other solutions need to be found, the algorithm can simply resume its operations at the leaf at which it stopped. Alternatively, we can use the board‘s symmetry for this purpose.

SUBSET-SUM PROBLEM

Subset-Sum Problem is

finding a subset of a given set S = {s1,s2….sn}

of n positive integers whose sum is equal to a given positive

integer d.

For

example, for S = {1, 2, 5, 6, 8) and d = 9, there are two solutions: {1, 2, 6}

and {1, 8}. Of course, some instances of this problem may have no solutions.

that s1

≤ s2

≤ ……. ≤ sn

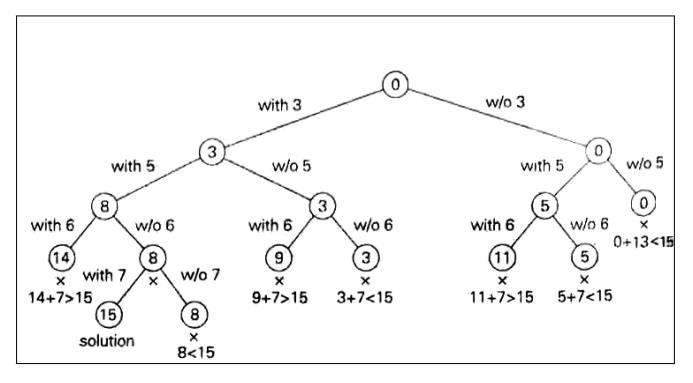

The

state-space tree can be constructed as a binary tree as that in the following

figure for the instances S = (3, 5, 6, 7) and d = 15.

The root

of the tree represents the starting point, with no decisions about the given

elements made as yet.

Its left

and right children represent, respectively, inclusion and exclusion ofs1 in a

set being sought.

Similarly,

going to the left from a node of the first level corresponds to inclusion of

s2, while going to the right corresponds to its exclusion, and soon.

Thus, a

path from the root to a node on the ith level of the tree indicates which of

the first i numbers have been included in the subsets represented by that node.

We record

the value of s‘ the sum of these numbers, in the node, Ifs is equal to d. we

have a solution to the problem.

We can

either, report this result and stop or, if all the solutions need to he found,

continue by backtracking to the node‘s parent.

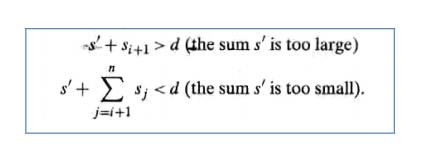

If s‘ is

not equal to d, we can terminate the node as nonpromising if either of the two

inequalities holds:

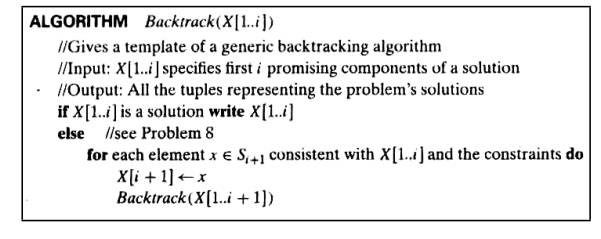

1. Pseudocode For Backtrack

Algorithms

Fig: Complete state-space tree of

the backtracking algorithm

(applied

to the instance S = (3, 5, 6, 7) and d = 15 of the subset-sum problem. The

number inside a node is the sum of

the elements already included in subsets represented by the node. The

inequality below a leaf indicates the reason for its termination)

GRAPH COLORING

A

coloring of a graph is an assignment of a color to each vertex of the graph so

that no two vertices connected by an edge have the same color. It is not hard

to see that our problem is one of coloring the graph of incompatible turns

using as few colors as possible.

The

problem of coloring graphs has been studied for many decades, and the theory of

algorithms tells us a lot about this problem. Unfortunately, coloring an

arbitrary graph with as few colors as possible is one of a large class of

problems called "NP-complete problems," for which all known solutions

are essentially of the type "try all possibilities."

A

k-coloring of an undirected graph G = (V, E) is a function c : V → {1, 2,...,

k} such that c(u) ≠ c(v) for every edge (u, v) E. In other words, the numbers

1, 2,..., k represent the k colors, and adjacent vertices must have different

colors. The graph-coloring problem is to determine the minimum number of colors

needed to color a given graph.

a. Give an efficient algorithm to determine a 2-coloring of a graph if one exists.

b.

Cast the graph-coloring problem as a decision

problem. Show that your decision problem is solvable in polynomial time if and

only if the graph-coloring problem is solvable in polynomial time.

c.

Let the language 3-COLOR be the set of graphs that

can be 3-colored. Show that if 3-COLOR is NP-complete, then your decision

problem from part (b) is NP-complete.

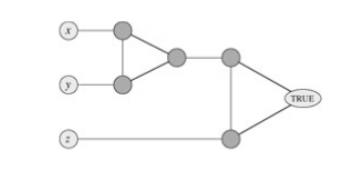

To prove

that 3-COLOR is NP-complete, we use a reduction from 3-CNF-SAT. Given a formula

φ of m clauses on n variables x, x,..., x, we construct a graph G = (V, E) as

follows.

The set V

consists of a vertex for each variable, a vertex for the negation of each

variable, 5 vertices for each clause, and 3 special vertices: TRUE, FALSE, and

RED. The edges of the graph are of two types: "literal" edges that

are independent of the clauses and "clause" edges that depend on the

clauses. The literal edges form a triangle on the special vertices and also

form a triangle on x, ¬x, and RED for i = 1, 2,..., n.

d.

Argue that in any 3-coloring c of a graph

containing the literal edges, exactly one of a variable and its negation is

colored c(TRUE) and the other is colored c(FALSE).

Argue

that for any truth assignment for φ, there is a 3-coloring of the graph

containing just the literal edges.

The

widget is used to enforce the condition corresponding to a clause (x y z). Each

clause requires a unique copy of the 5 vertices that are heavily shaded; they

connect as shown to the literals of the clause and the special vertex TRUE.

e.

Argue that if each of x, y, and z is colored

c(TRUE) or c(FALSE), then the widget is 3-colorable if and only if at least one

of x, y, or z is colored c(TRUE).

f.

Complete the proof that 3-COLOR is NP-complete.

Fig: The

widget corresponding to a clause (x y

z), used in Problem

HAMILTONIAN CIRCUIT PROBLEM

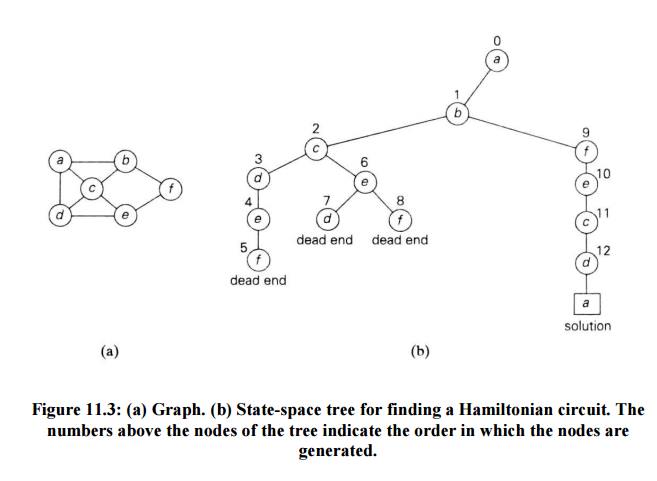

As our

next example, let us consider the problem of finding a Hamiltonian circuit in

the graph of Figure 11.3a. Without loss of generality, we can assume that if a

Hamiltonian circuit exists, it starts at vertex a. Accordingly, we make vertex

a the root of the state-space tree (Figure 11.3b).

The first

component of our future solution, if it exists, is a first intermediate vertex

of a Hamiltonian cycle to be constructed. Using the alphabet order to break the

three-way tie among the vertices adjacent to a, we select vertex b. From b, the

algorithm proceeds to c, then to d, then to e, and finally to f, which proves

to be a dead end. So the algorithm backtracks from f to e, then to d. and then

to c, which provides the first alternative for the algorithm to pursue.

Going

from c to e eventually proves useless, and the algorithm has to backtrack from

e to c and then to b. From there, it goes to the vertices f, e, c, and d, from

which it can legitimately return to a, yielding the Hamiltonian circuit a, b,

f, e, c, d, a. If we wanted to find another Hamiltonian circuit, we could

continue this process by backtracking from the leaf of the solution found.

Figure 11.3: (a) Graph. (b)

State-space tree for finding a Hamiltonian circuit. The numbers above the nodes

of the tree indicate the order in which the nodes are generated.

KNAPSACK PROBLEM

The

knapsack problem or rucksack problem is a problem in combinatorial

optimization: Given a set of items, each with a weight and a value, determine

the number of each item to include in a collection so that the total weight is

less than a given limit and the total value is as large as possible.

It

derives its name from the problem faced by someone who is constrained by a

fixed-size knapsack and must fill it with the most useful items.

The

problem often arises in resource allocation with financial constraints. A

similar problem also appears in combinatorics, complexity theory, cryptography

and applied mathematics.

The

decision problem form of the knapsack problem is the question "can a value

of at least V be achieved without exceeding the weight W?"

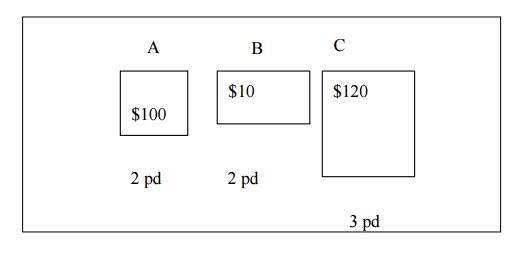

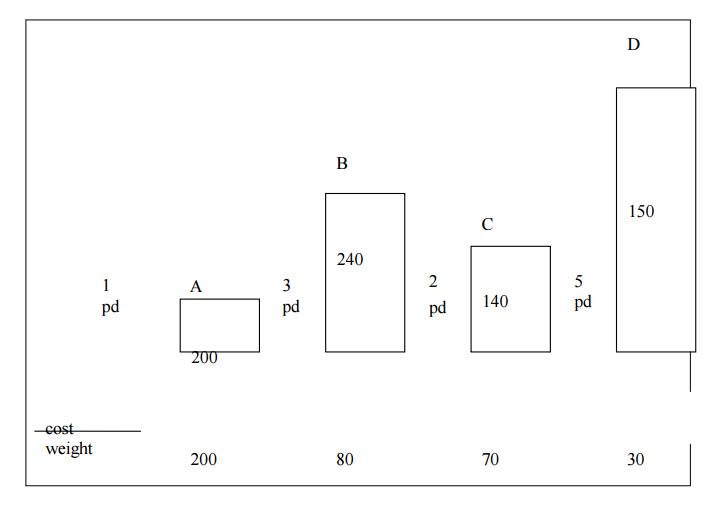

E.g. A

thief enters a store and sees the following items:

His

Knapsack holds 4 pounds.

What

should he steal to maximize profit?

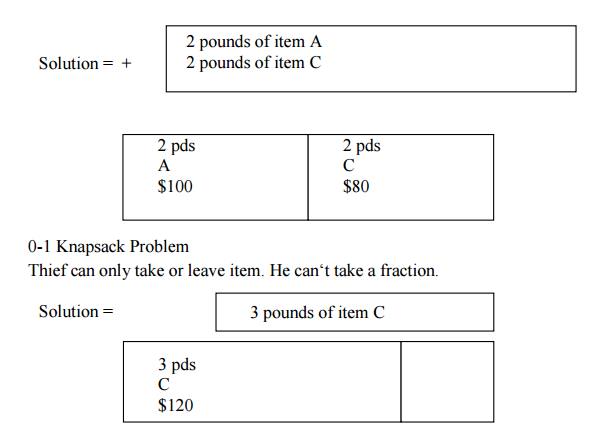

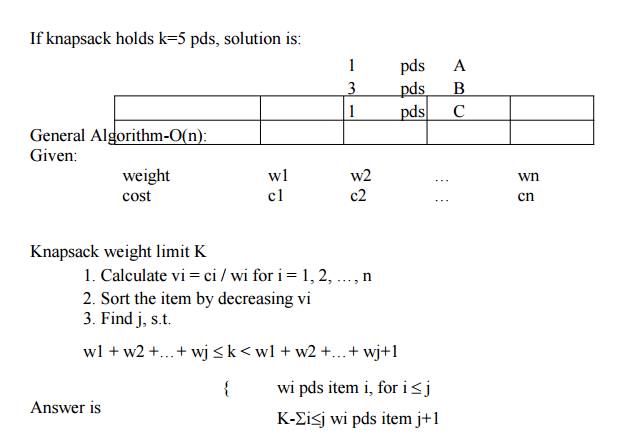

Fractional

Knapsack Problem

Thief can

take a fraction of an item.

Fractional

Knapsack has a greedy solution

Sort

items by decreasing cost per pound

Related Topics