Chapter: Medical Surgical Nursing: Assessment of Integumentary Function

Assessment of Integumentary Function

Assessment

HEALTH HISTORY AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

When

caring for patients with dermatologic disorders, the nurse obtains important

information through the health history and di-rect observations. The nurse’s

skill in physical assessment and an understanding of the anatomy and function

of the skin can en-sure that deviations from normal are recognized, reported,

and documented.

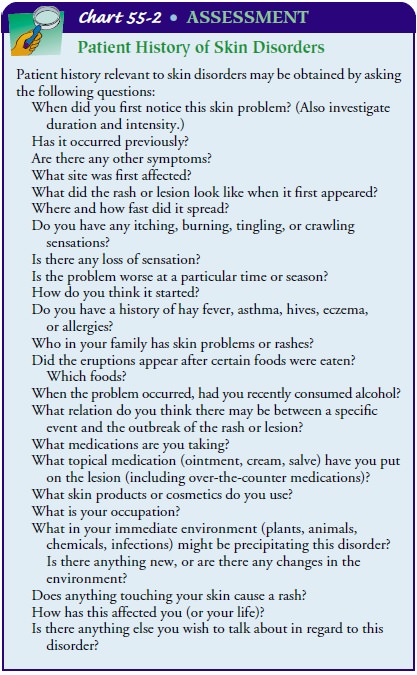

During the health history interview, the nurse asks about any family and personal history of skin allergies, allergic reactions to food, medications, chemicals, previous skin problems, and skin cancer.

The names of

cosmetics, soaps, shampoos, and other per-sonal hygiene products are obtained

if there have been any recent skin problems noticed with the use of these

products. The health history contains specific information about the onset, signs

and symptoms, location, and duration of any pain, itching, rash, or other

discomfort experienced by the patient. The accompanying as-sessment chart lists

selected questions useful in obtaining appropri-ate information (Chart 55-2).

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

Assessment of the skin involves the entire skin area, including the mucous membranes, scalp, hair, and nails. The skin is a reflection of a person’s overall health, and alterations commonly correspond to disease in other organ systems. Inspection and palpation are techniques commonly used in examining the skin. The room must be well lighted and warm. A penlight may be used to highlight lesions. The patient completely disrobes and is adequately draped. Gloves are worn during skin examination if rash or lesions are to be palpated. However, it is important to avoid making the patient feel as if he or she cannot be touched. Touching skin lesions in-dicates a level of acceptance of the patient.

Assessing General Appearance

The

general appearance of the skin is assessed by observing color, temperature,

moisture or dryness, skin texture (rough or smooth), lesions, vascularity,

mobility, and the condition of the hair and nails. Skin turgor, possible edema,

and elasticity are assessed by palpation.

Skin

color varies from person to person and ranges from ivory to deep brown to

almost pure black. The skin of exposed portions of the body, especially in

sunny, warm climates, tends to be more pigmented than the rest of the body. The

vasodilation that occurs with fever, sunburn, and inflammation produces a pink

or reddish hue to the skin. Pallor is an absence of or a decrease in normal

skin color and vascularity and is best observed in the conjunctivae or around

the mouth.

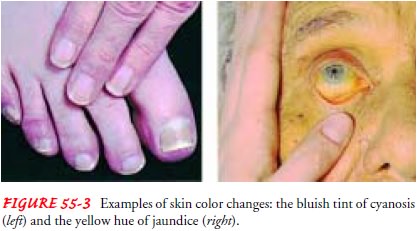

The

bluish hue of cyanosis indicates cellular hypoxia and is easily observed in the

extremities, nail beds, lips, and mucous membranes. Jaundice, a yellowing of

the skin, is directly related to elevations in serum bilirubin and is often

first observed in the sclerae and mucous membranes (Fig. 55-3).

Erythema

Erythema

is redness of the skin

caused by the congestion of cap-illaries. In light-skinned people, it is easily

observed at any loca-tion where it appears. To determine possible inflammation,

the skin is palpated for increased warmth and for smoothness (ie, edema) or

hardness (ie, intracellular infiltration). Because dark skin tends to assume a

purple-gray cast when an inflammatory process is present, it may be difficult

to detect erythema.

Rash

In instances of pruritus (ie, itching), the patient should be asked to indicate which areas of the body are involved. The skin is then stretched gently to decrease the reddish tone and make the rash stand out. Pointing a penlight laterally across the skin may ef-fectively highlight the rash. The differences in skin texture are then assessed by running the tips of the fingers lightly over the skin. The borders of the rash may be palpable. The patient’s mouth and ears are included in the examination. (Sometimes rubeola, or measles, causes a red cast to appear on the tip of the ears.) The patient’s temperature is assessed, and the lymph nodes are palpated.

Cyanosis

Cyanosis

is the bluish discoloration that results from a lack of oxygen in the blood. It

appears with shock or with respiratory or circulatory compromise. In people

with light skin, cyanosis man-ifests as a bluish hue to the lips, fingertips,

and nail beds. Other indications of decreased tissue perfusion include cold,

clammy skin; a rapid, thready pulse; and rapid, shallow respirations. The

conjunctivae of the eyelids are examined for pallor and petechiae (ie, pinpoint red spots that appear on the skin as a

result of blood leakage into the skin).

In

a person with dark skin, the skin usually assumes a grayish cast. To detect

cyanosis, the areas around the mouth and lips and over the cheekbones and

earlobes should be observed.

Color Changes

Almost

every process that occurs on the skin causes some color change. For example, hypopigmentation (ie, decrease in the

melanin of the skin, resulting in a loss of pigmentation) may be caused by a

fungal infection, eczema, or vitiligo

(ie, condition characterized by destruction of the melanocytes in

circum-scribed areas of the skin, resulting in white patches). Hyper-pigmentation (ie, increase in the

melanin of the skin, resultingin increased pigmentation) may occur after

disease or injury to the skin (ie, postinflammatory), after sun injury, or as a

result of aging.

Changes

in skin color in people with dark skin are more no-ticeable and may cause more

concern because the discoloration is more readily visible. Some variation in

skin pigment levels is con-sidered normal. Examples include the pigmented

crease across the bridge of the nose, pigmented streaks in the nails, and

pigmented spots on the sclera of the eye. Many variations of color are

genet-ically determined.

ASSESSING PATIENTS WITH DARK SKIN

The

color gradations that occur in people with dark skin are largely determined by

genetic transmission; they may be described as light, medium, or dark. In

people with dark skin, melanin is produced at a faster rate and in larger

quantities than in people with light skin. Healthy dark skin has a reddish base

or under-tone. The buccal mucosa, tongue, lips, and nails normally are pink.

The degree of pigmentation of the patient’s skin may affect the appearance of a

lesion. Lesions may be black, purple, or gray instead of the tan or red seen in

patients with light skin. Dark pig-ment responds with discoloration after

injury or inflammation, and patients with dark skin more often experience

post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation than those with lighter skin. The

hyperpigmentation eventually fades but may require months to a year to do so.

In

general, people with dark skin suffer the same skin condi-tions as those with

light skin. They are less likely to have skin can-cer but more likely to have

keloid or scar formation and disorders resulting from occlusion or blockage of

hair follicles.

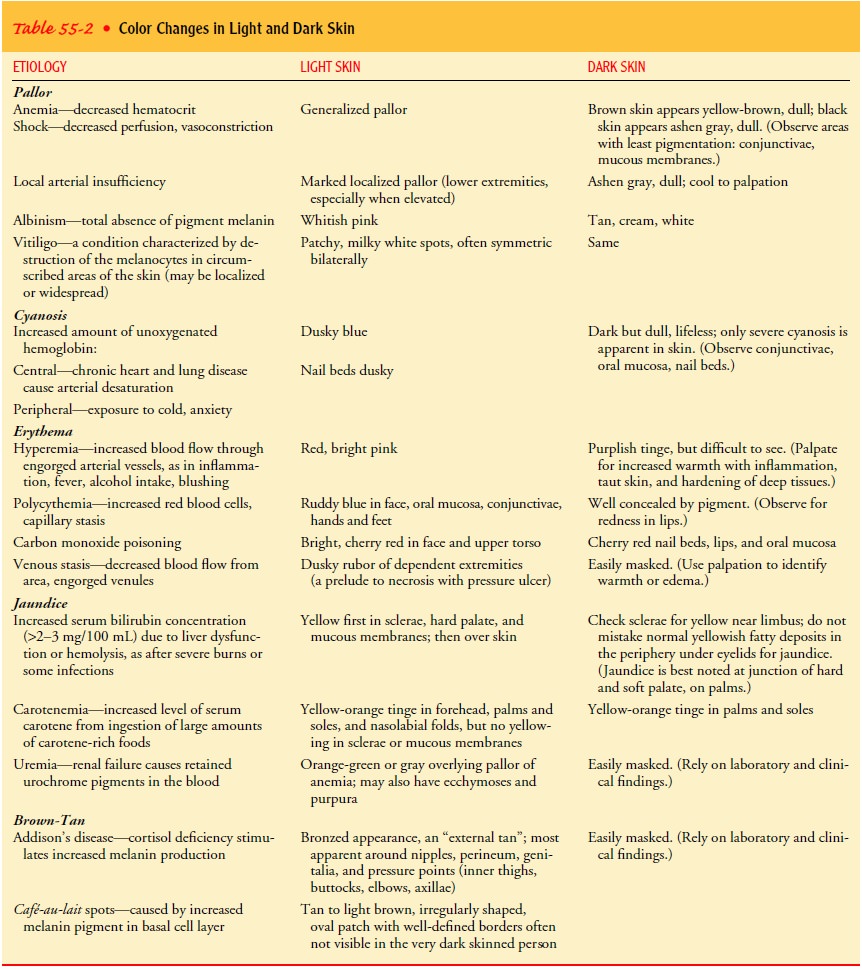

Table

55-2 provides an overview of color changes in light-skinned and dark-skinned

people, and the following section pro-vides specific guidelines for assessing

dark and light skin.

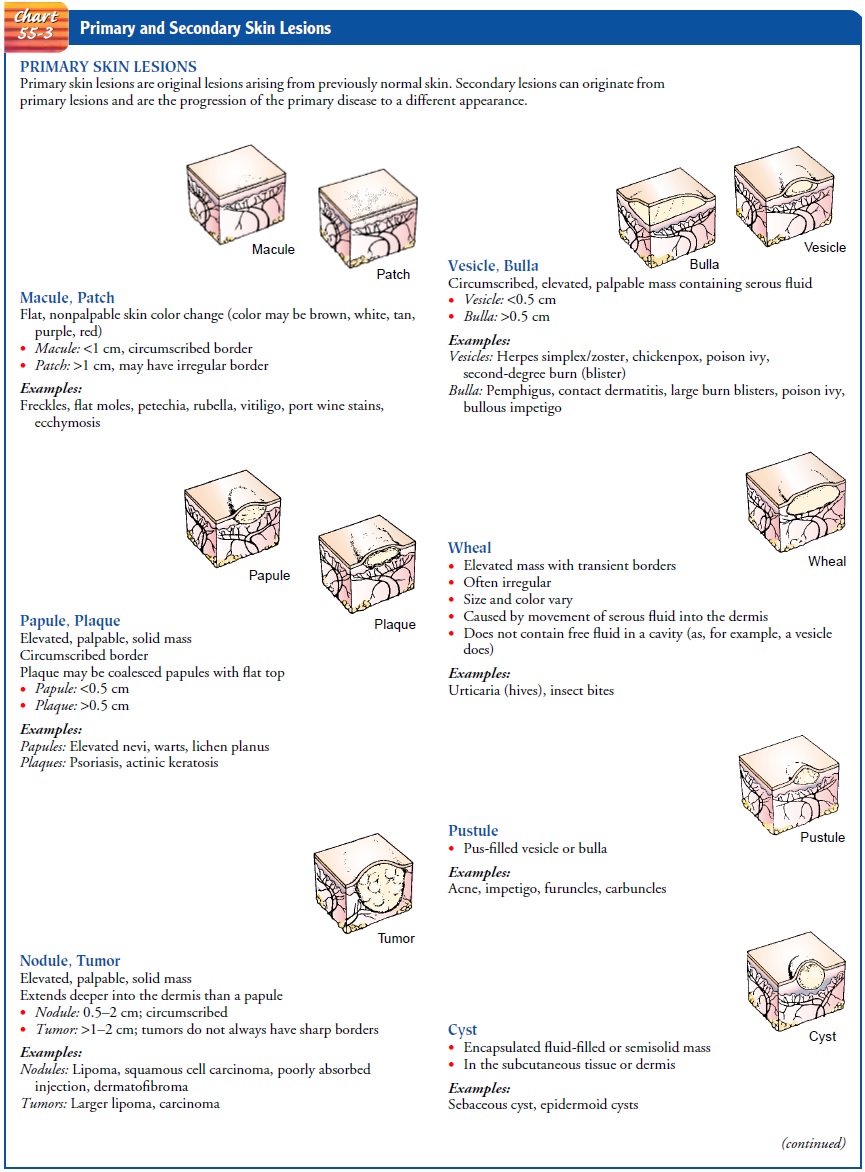

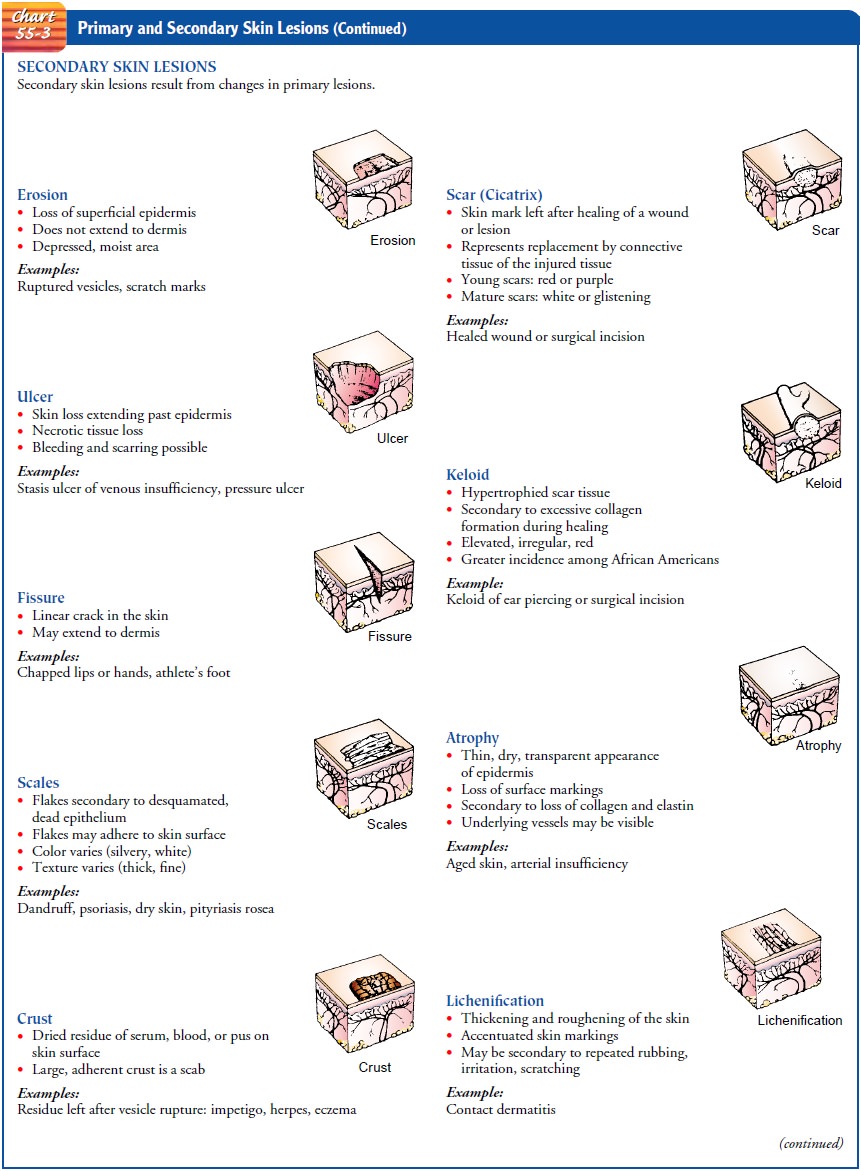

ASSESSING SKIN LESIONS

Skin lesions are the most prominent characteristics

of dermato-logic conditions. They vary in size, shape, and cause and are

clas-sified according to their appearance and origin. Skin lesions canbe

described as primary or secondary. Primary lesions are the ini-tial lesions and

are characteristic of the disease itself. Secondary lesions result from

external causes, such as scratching, trauma, in-fections, or changes caused by

wound healing. Depending on the stage of development, skin lesions are further

categorized accord-ing to type and appearance (Chart 55-3).

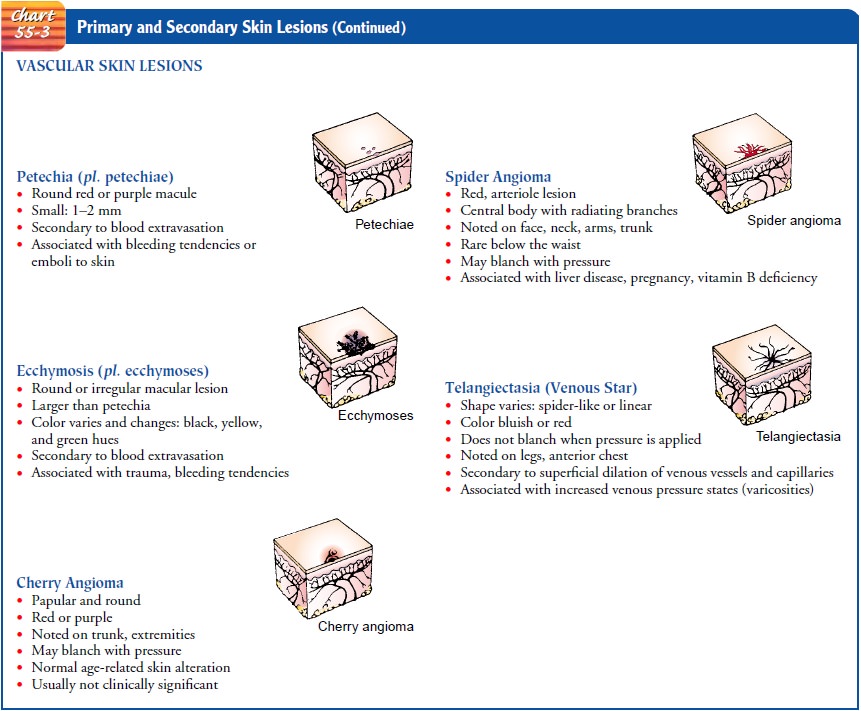

A preliminary assessment of the eruption or lesion

should help to identify the type of dermatosis

(ie, abnormal skin condition) and indicate whether the lesion is primary or

secondary. At the same time, the anatomic distribution of the eruption should

be ob-served, because certain diseases affect certain sites of the body and are

distributed in characteristic patterns and shapes (Figs. 55-4 and 55-5). To

determine the extent of the regional distribution, the left and right sides of

the body should be compared while the color and shape of the lesions are

assessed. After observation, the lesions are palpated to determine their

texture, shape, and border and to see if they are soft and filled with fluid or

hard and fixed to the surrounding tissue.

A

metric ruler is used to measure the size of the lesions so that any further

extension can be compared with this baseline mea-surement. The dermatosis is

documented on the patient’s health record; it should be described clearly and

in detail, using precise terminology.

After

the characteristic distribution of the lesions has been de-termined, the

following information should be obtained and described clearly and in detail:

·

Color of the lesion

·

Any redness, heat, pain, or

swelling

·

Size and location of the

involved area

·

Pattern of eruption (eg,

macular, papular, scaling, oozing, discrete, confluent)

·

Distribution of the lesion

(eg, bilateral, symmetric, linear, circular)

If

acute open wounds or lesions are found on inspection of the skin, a

comprehensive assessment should be made and docu-mented in the patient’s

record. This assessment should address several issues:

·

Wound bed: Inspect for

necrotic and granulation tissue, epithelium, exudate, color, and odor.

·

Wound edges and margins:

Observe for undermining (ie, extension of the wound under the surface skin),

and evalu-ate for condition.

·

Wound size: Measure in

millimeters or centimeters, as ap-propriate, to determine diameter and depth of

the wound and surrounding erythema.

·

Surrounding skin: Assess for

color, suppleness and mois-ture, irritation, and scaling.

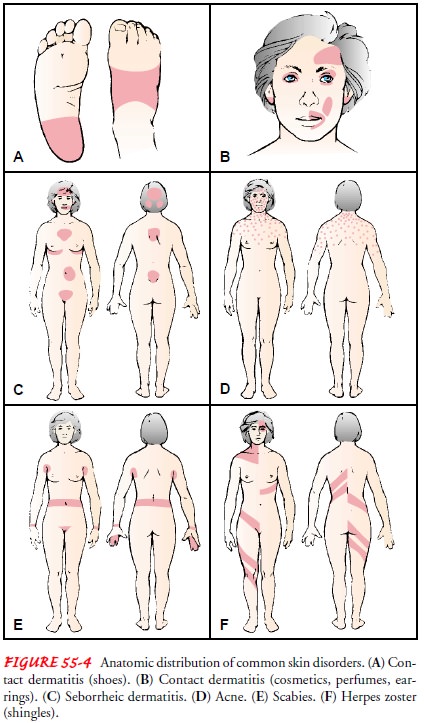

Assessing Vascularity and Hydration

After

the color of the skin has been evaluated and lesions have been inspected, an

assessment of vascular changes in the skin is performed. A description of

vascular changes includes location, distribution, color, size, and the presence

of pulsations. Common vascular changes include petechiae, ecchymoses, telangiectases (ie, red marks on the

skin caused by stretching of the superficial blood vessels), angiomas, and

venous stars.

Skin moisture, temperature, and texture are assessed primar-ily by palpation. The elasticity (ie, turgor) of the skin, which de-creases in normal aging, may be a factor in assessing the hydration status of a patient.

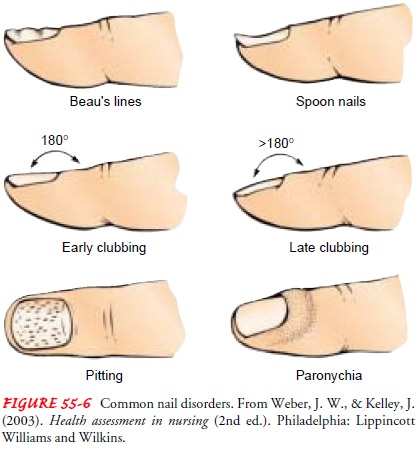

Assessing the Nails and Hair

A brief inspection of the nails includes observation of configura-tion, color, and consistency. Many alterations in the nail or nail bed reflect local or systemic abnormalities in progress or resulting from past events (Fig. 55-6). Transverse depressions known as Beau’s lines in the nails may reflect retarded growth of the nail matrix because of severe illness or, more commonly, local trauma. Ridging, hypertrophy, and other changes may also be visible with local trauma. Paronychia, an inflammation of the skin around the nail, is usually accompanied by tenderness and erythema. The angle between the normal nail and its base is 160 degrees. When palpated, the nail base is usually firm. Clubbing is manifested by a straightening of the normal angle (180 degrees or greater) and softening of the nail base. The softened area feels spongelike when palpated.

The hair assessment is carried out by inspecting

and palpating. Gloves are worn, and the examination room should be well

lighted. Separating the hair so that the condition of the skin underneath can

be easily seen, the nurse assesses color, texture, and distribu-tion. Any

abnormal lesions, evidence of itching, inflammation, scaling, or signs of

infestation (ie, lice or mites) are documented.

COLOR AND TEXTURE

Natural

hair color ranges from white to black. Hair color begins to gray with age,

initially appearing during the third decade of life, when the loss of melanin begins

to become apparent. However, it is not unusual for the hair of younger people

to turn gray as a re-sult of hereditary traits. The person with albinism (ie,

partial or complete absence of pigmentation) has a genetic predisposition to

white hair from birth. The natural state of the hair can be altered by using

hair dyes, bleaches, and curling or relaxing products. The types of products

used are identified during the assessment.

The

texture of scalp hair ranges from fine to coarse, silky to brittle, oily to

dry, and shiny to dull, and hair can be straight, curly, or kinky. Dry, brittle

hair may result from overuse of hair dyes, hair dryers, and curling irons or

from endocrine disorders, such as thyroid dysfunction. Oily hair is usually

caused by in-creased secretion from the sebaceous glands close to the scalp. If

the patient reports a recent change in hair texture, the underlying reason is

pursued; the alteration may arise simply from the over-use of commercial hair

products or from changing to a new shampoo.

DISTRIBUTION

Body

hair distribution varies with location. Hair over most of the body is fine,

except in the axillae and pubic areas, where it is coarse. Pubic hair, which

develops at puberty, forms a diamond shape extending up to the umbilicus in boys

and men. Female pubic hair resembles an inverted triangle. If the pattern found

is more characteristic of the opposite gender, it may indicate an en-docrine

problem and further investigation is in order. Racial dif-ferences in hair are

expected, such as straight hair in Asians and curly, coarser hair in people of

African descent.

Men tend to have more body and facial hair than women. Loss of hair, or alopecia, can occur over the entire body or be confined to a specific area. Scalp hair loss may be localized to patchy areas or may range from generalized thinning to total baldness.

When assessing scalp hair loss, it is important to in-vestigate the underlying

cause with the patient. Patchy hair loss may be from habitual hair pulling or

twisting; from excessive traction on the hair (eg, braiding too tightly);

excessive use of dyes, straighteners, and oils; chemotherapeutic agents (eg,

doxo-rubicin, cyclophosphamide); fungal infection; or moles or lesions on the

scalp. Regrowth may be erratic, and distribution may never attain the previous

thickness.

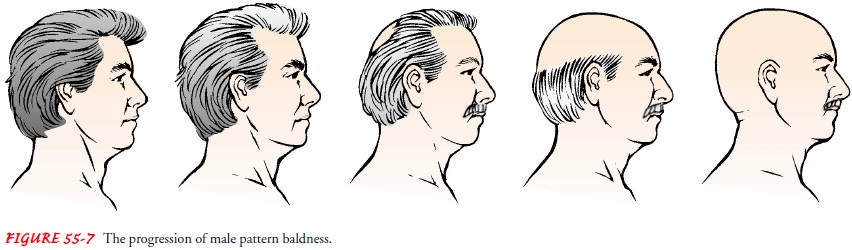

HAIR LOSS

The

most common cause of hair loss is male pattern baldness, which affects more

than one half of the male population and is believed to be related to heredity,

aging, and androgen (male hormone) levels. Androgen is necessary for male

pattern bald-ness to develop. The pattern of hair loss begins with receding of

the hairline in the frontal-temporal area and progresses to gradual thinning

and complete loss of hair over the top of the scalp and crown. Figure 55-7

illustrates the typical male pattern hair loss.

OTHER CHANGES

Male

pattern hair distribution may be seen in some women at the time of menopause,

when the hormone estrogen is no longer pro-duced by the ovaries. In women with

hirsutism, excessive hair may grow on the face, chest, shoulders, and pubic

area. When menopause is ruled out as the underlying cause, hormonal

ab-normalities related to pituitary or adrenal dysfunction must be

investigated.

Because

patients with skin conditions may be viewed nega-tively by others, these

patients may become distraught and avoid interaction with people. Skin

conditions can lead to disfigure-ment, isolation, job loss, and economic

hardship.

Some conditions may subject the patient to a

protracted illness, leading to feelings of depression, frustration,

self-consciousness, poor self-image, and rejection. Itching and skin

irritation, fea-tures of many skin diseases, may be a constant annoyance. The

results of these discomforts may be loss of sleep, anxiety, and de-pression,

all of which reinforce the general distress and fatigue that frequently

accompany skin disorders.

For patients suffering such physical and psychological

dis-comforts, the nurse needs to provide understanding, explanations of the

problem, appropriate instructions related to treatment, nursing support,

patience, and encouragement. It takes time to help patients gain insight into

their problems and resolve their difficulties. It is imperative to overcome any

aversion that may be felt when caring for patients with unattractive skin

disorders. The nurse should show no sign of hesitancy when approaching

pa-tients with skin disorders. Such hesitancy only reinforces the

psy-chological trauma of the disorder.

Related Topics