Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : The Difficult Airway

Are the risk factors for difficult intubation reliable predictors of difficult intubation?

Are the risk factors for difficult intubation reliable predictors

of difficult intubation?

Although it makes intuitive sense to perform,

and is consistent with best medical practices, airway evaluation frequently

falls short of its intended goal. Numerous rating systems based on recognized

prediction criteria have been investigated. Most suffer from recurrent

problems.

The first problem is nomenclature. A

standardized definition of the “difficult airway” did not exist until 1993. At

that time it was explained as a situation in which a con-ventionally trained

anesthesiologist experienced difficulty with mask ventilation, difficulty with

tracheal intubation, or both. For years, individual investigators needed to

estab-lish their own definition of “difficult intubation” each time studies were

conducted. Consequently, the endpoints of their work were not necessarily

comparable to other investigations in the field, making comparative analysis of

studies impossible. In 1993, the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ (ASA)

Committee on Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway offered

a generally acceptable definition. Ten years later the definition was altered

slightly. In 2003, “difficult tracheal intubation” referred to any intubation

that required multiple attempts. This is a good clinical definition but lacks

the precision required for scientific investigation. For example, some

practitioners may perform a single laryngoscopy and, based upon the view

obtained, elect to forego further attempts at laryngoscopy. Such cases may be

handled with a supraglottic airway device, regional anesthesia, or other

techniques. This situation does not meet the defini-tion of difficult

intubation, when in fact it would have if one more attempt at intubation was

performed. Thus, the ASA’s definition serves as a good clinical understanding

of difficult intubation, but lacks the rigid, encompassing concerns required

for scientific investigation. “Failed intubation” is an easier term to

understand. A failed intubation exists when laryngoscopists give up and admit

that traditional intubation will not be successful. The end-point is clear and

occurs with an incidence of 1:280 in obstetric patients and 1:2,230 in the

general operating room population.

The second problem is identifying features that

predict difficult intubation. This is frequently accomplished by attempting to

recognize characteristics found in patients who have proven to be difficult

intubations. The problem with such an approach is the lack of information about

the same characteristics in patients who are easy intubations. As Turkan points

out, we do not even know the normal values for many prediction criteria. A

better method is to apply multivariate analysis to patient populations in a

prospective manner. In that way, a single factor can be compared for difficult

and easy intubations. Various rating systems attempt to combine multiple

predictors into a formula. To date, none are satisfactory.

The third problem is validating the tests, once

they are promulgated. Validation tests performed on the same patient population

used to identify them are misleading. This is like counting the number of

envelopes in a par-ticular mail box, predicting that all mailboxes contain that

number of envelopes, and then validating the prediction by re-counting the

envelopes in that same mailbox. Validation must be performed by counting the

envelopes in multiple different mailboxes. In the same way, validation of

difficult intubation predictors must be performed in multiple different patient

populations. The experimental patient sample cannot be used to validate

experimental results. Different sample populations are needed for that.

The fourth problem is the experimental methods.

Individual practitioners differ and clinical practice has shown that a

particular patient who is difficult to intubate in the hands of one

laryngoscopist may be successfully intubated by another laryngoscopist. In this

way, experi-mental designs utilizing more than one laryngoscopist introduce a

source of variation, which detracts from attempts to control experimental

conditions. Relying on a single laryngoscopist obviates this problem, but

limits the number of patients that can be enrolled into a single study. Another

source of experimental error is observer variation. Observations performed by

different experimenters are subject to variations and introduce another source

of erro-neous data. The best way to prevent this problem is for all

observations to be performed by a single experimenter. This too may limit the number

of patients enrolled in a single study.

Statistical tests for assessing the usefulness

of criteria include sensitivity and positive predictive value. Sensitivity is

the ratio of correctly identified difficult intubation patients to all the

difficult intubation patients within the entire patient population. For

example, take a patient popu-lation in which 5 are difficult to intubate. If a

particular predictor of difficult intubation correctly identifies all 5

patients, then its sensitivity is 100%. If the test correctly identifies only 2

of the 5 patients, then its sensitivity is 2/5 or 40%. Positive predictive

value is the probability that difficult intubation patients identified by the

test are in fact difficult to intubate. If the test predicts that 5 patients

will be difficult to intubate and all 5 of those patients are difficult to

intubate then its positive predictive value is 100%. If the test predicts that

10 patients will be difficult to intubate but only 5 of them are difficult to

intubate, then its predictive value is 5/10 or 50%. Unfortunately, statistical

tests such as sensitivity and positive predictive value applied to classic

prediction criteria have yielded disap-pointing results.

In 1984, Cormack and Lehane described a grading

system for comparing laryngoscopic views as follows:

· Grade I: the entire glottic opening

· Grade II: the posterior laryngeal aperture but

not the anterior portion

· Grade III: the epiglottis but not any part of

the larynx

· Grade IV: the soft palate but not the epiglottis

Early evidence indicated good correlation

between Mallampati/Samsoon classes and laryngoscopic grades. In other words, as

the Mallampati/Samsoon classes increased in number, the prediction was that

corresponding laryngo-scopic grades would also increase in number, for any

given patient. This concept formed the basis for using Mallampati/Samsoon

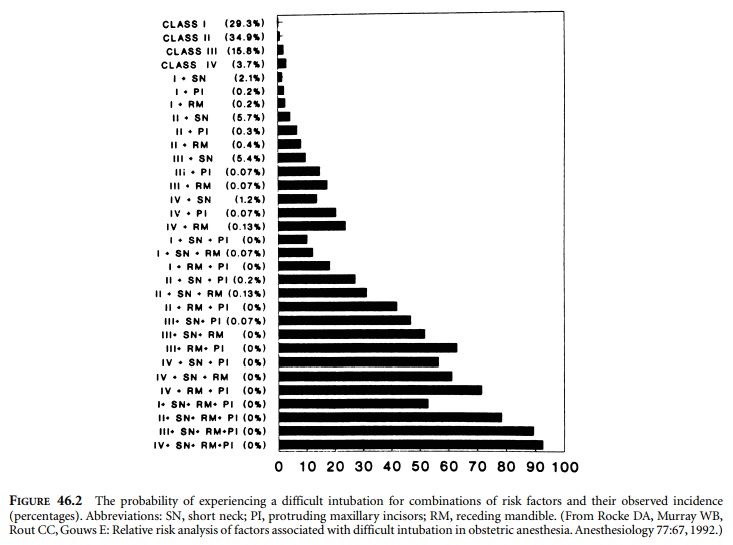

classes to predict difficult intuba-tion. In 1992, Rocke et al. disproved that

relationship. Rocke and colleagues investigated several classic predictors of

difficult intubation and demonstrated that none of the ones they studied were

reliable predictors of difficult intubation (Figure 46.2). Classic prediction

criteria essentially deal with surface anatomy. They screen for some factors

that are associated with difficult intubation, but fail to address others. Some

potential problems are hidden from surface anatomy examinations. Subglottic,

glottic, and supraglottic abnormalities, such as tracheal stenosis, lingual

tonsil hypertrophy, or epiglottic prolapse into the glottic opening, cannot be

diagnosed by standard physical examinations for predicting difficult

intubation. Pathophysiologic factors such as mobile TMJ discs or disc fragments

can produce severely limited mouth opening following induction of anesthesia, when

none existed before. Precise measurements of atlanto-axial motion sometimes

fail to predict difficult intubation. These factors and others may be

unrecognized by standard tests but complicate intubation, nonetheless. At the

time of this writing, no single factor

reliably predicts difficult intubation. The

likelihood of a difficult intubation increases when mul-tiple predictors are

present in a patient at the same time.

Related Topics