Chapter: Software Architectures : Architectural Views

Architectural Views

An

architectural view is a way to portray those aspects or elements of the

architecture that are relevant to the concerns the view intends to address—and,

by implication, the stakeholders for whom those concerns are important. This

idea is not new, going back at least as far as the work of David Parnas in the

1970s and more recently Dewayne Perry and Alexander Wolf in the early 1990s.

However,

it wasn’t until 1995 that Phillipe Kruchten of the Rational Corporation

published his widely accepted written description of viewpoints, Architectural

Blueprints—The 4+1 View Model of Software Architecture. This suggested four

different views of a system and the use of a set of scenarios (use cases) to

check their correctness. Kruchten’s approach has since evolved to form an

important part of the Rational Unified Process (RUP).

More

recently, IEEE Standard 1471 has formalized these concepts and brought some

welcome standardization of terminology. In fact, our definition of a view is

based on and extends the one from the IEEE standard.

Definition:

A view is a representation of one or more structural aspects of an architecture

that illustrates how the architecture addresses one or more concerns held by

one or more of its stakeholders.

When

deciding what to include in a view, ask yourself the following questions. What

class(es) of stakeholder is the view aimed at? A view may be narrowly focused

on one class of stakeholder or even a specific individual, or it may be aimed

at a larger group whose members have varying interests and levels of expertise.

How much technical understanding do these stakeholders have? Acquirers and

users, for example, will be experts in their subject areas but are unlikely to

know much about hardware or software, while the converse may apply to

developers or support staff. What stakeholder concerns is the view intended to

address? How much do the stakeholders know about the architectural context and

background to these concerns? How much do these stakeholders need to know about

this aspect of the architecture? For non technical stakeholders such as users,

how competent are they in understanding its technical details? As with the AD

itself, one of your main challenges is to get the right level of detail into

your views. Provide too much detail, and your audience will be overwhelmed; too

little, and you risk your audience making assumptions that may not be valid.

Strategy:

Include in a view only the details that further the objectives of your AD—that

is, those details that help explain the architecture to stakeholders or

demonstrate that stakeholder concerns are being met.

Architectural Viewpoints

It

would be hard work if every time you were creating a view of your architecture

you had to go back to first principles to define what should go into it.

Fortunately, you don’t quite have to do that.

In

his introductory paper, Kruchten defined four standard views, namely, Logical,

Process, Physical, and Development. The IEEE standard makes this idea generic

(and does not specify one set of views or another) by proposing the concept of

a viewpoint. The objective of the viewpoint concept is an ambitious one—no less

than making available a library of templates and patterns that can be used off

the shelf to guide the creation of an architectural view that can be inserted

into an AD. We define a viewpoint (again after IEEE Standard 1471) as follows.

Definition:

A viewpoint is a collection of patterns, templates, and conventions for

constructing one type of view. It defines the stakeholders whose concerns are

reflected in the viewpoint and the guidelines, principles, and template models

for constructing its views.

Architectural

viewpoints provide a framework for capturing reusable architectural knowledge

that can be used to guide the creation of a particular type of (partial) AD. In

a relatively unstructured activity like architecture definition, the idea of

the viewpoint is very appealing. If we can define a standard approach, a

standard language, and even a standard metamodel for describing different

aspects of a system, stakeholders can understand any AD that conforms to these

standards once familiar with them. In practice, of course, we haven’t achieved

this goal yet. There are no universally accepted ways to model software

architectures, and every AD uses its own conventions. However, the widespread

acceptance of techniques such as entity-relationship models and of modeling

languages such as UML takes us some way toward this goal. In any case, it is

extremely useful to be able to categorize views according to the types of

concerns and architectural elements they present.

Strategy:

When developing a view, whether or not you use a formally defined viewpoint, be

clear in your own mind what sorts of concerns the view is addressing, what

types of architectural elements it presents, and who the viewpoint is aimed at.

Make sure that your stakeholders understand these as well.

Interrelationships

Between the Core Concepts

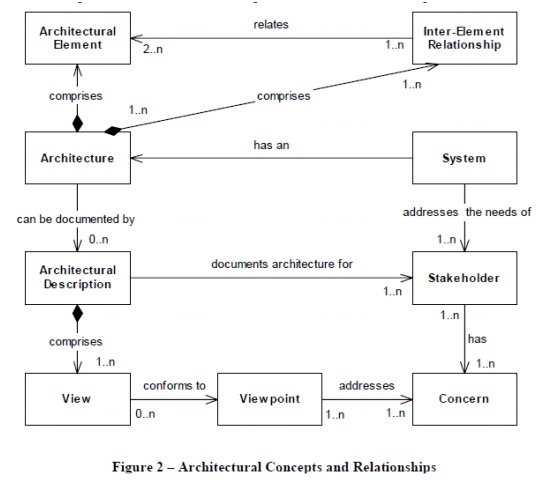

To

put views and viewpoints in context, consider the conceptual model in Figure 2,

which illustrates how views and viewpoints relate to the other important

architectural concepts we introduced earlier.

The

concepts and relationships shown in this diagram can be summarised as follows

.

• A system is built to address the needs, concerns, goals and objectives of its

stakeholders.

• The

architecture of a system is characterized by its static and dynamic structures,

and its externally-visible behavior and properties.

• The

architecture of a system is comprised of a number of architectural elements and

their interrelationships.

• The

architecture of a system can potentially be documented by an architectural

description (fully, partly or not at all). In fact, there are many potential

ADs for a given architecture, some good, some bad.

• An

architectural description documents an architecture for its stakeholders, and

demonstrates to them that it has met their needs.

• A

viewpoint defines the aims, intended audience, and content of a class of views

and defines the concerns that views of this class will address.

• A

view conforms to a viewpoint and so communicates the resolution of a number of

concerns (and a resolution of a concern may be communicated in a number of

views).

• An

architectural description comprises a number of views. The Benefits of Using

Viewpoints and Views

The Benefits of Using Viewpoints

and Views

Using

views and viewpoints to describe the architecture of a system benefits the

architecture definition process in a number of ways.

• Separation

of concerns: Describing many aspects of the system via a single representation

can cloud communication and, more seriously, can result in independent aspects

of the system becoming intertwined in the model. Separating different models of

a system into distinct (but related) descriptions helps the design, analysis,

and communication processes by allowing you to focus on each aspect separately.

• Communication

with stakeholder groups: The concerns of each stakeholder group are typically

quite different (e.g., contrast the primary concerns of end users, security

auditors, and help-desk staff), and communicating effectively with the various

stakeholder groups is quite a challenge. The viewpoint-oriented approach can

help considerably with this problem. Different stakeholder groups can be guided

quickly to different parts of the AD based on their particular concerns, and

each view can be presented using language and notation appropriate to the

knowledge, expertise, and concerns of the intended readership.

• Management

of complexity: Dealing simultaneously with all of the aspects of a large system

can result in overwhelming complexity that no one person can possibly handle.

By treating each significant aspect of a system separately, the architect can

focus on each in turn and so help conquer the complexity resulting from their

combination.

• Improved

developer focus: The AD is of course particularly important for the developers

because they use it as the foundation of the system design. By separating out

into different views those aspects of the system that are particularly

important to the development team, you help ensure that the right system gets

built.

Related Topics