Chapter: Software Architectures : Architectural Views

Architectural Structures And Views

ARCHITECTURAL

STRUCTURES AND VIEWS

So it is with software. Modern

systems are more than complex enough to make it difficult to grasp them all at

once. Instead, we restrict our attention at any one moment to one (or a small

number) of the software system's structures. To communicate meaningfully about

an architecture, we must make clear which structure or structures we are

discussing at the moment?which view we are taking of the architecture.

We will be using the related terms

structure and view when discussing architecture representation. A view is a

representation of a coherent set of architectural elements, as written by and

read by system stakeholders. It consists of a representation of a set of

elements and the relations among them. A structure is the set ofelements itself,

as they exist in software or hardware. For example, a module structure is the

set of the system's modules and their organization. A module view is the

representation of that structure, as documented by and used by some system

stakeholders. These terms are often used interchangeably, but we will adhere to

these definitions.

Architectural

structures can by and large be divided into three groups, depending on the

broad nature of the elements they show.

Ōłæ

Module structures. Here the elements are modules, which

are units of implementation. Modules represent a code-based way of considering

the system. They are assigned areas of functional responsibility. There is less

emphasis on how the resulting software manifests itself at runtime. Module

structures allow us to answer questions such as What is the primary functional

responsibility assigned to each module? What other software elements is a

module allowed to use? What other software does it actually use? What modules

are related to other modules by generalization or specialization (i.e.,

inheritance) relationships?

Ōłæ

Component-and-connector structures. Here the elements are

runtime components (which are the principal units of computation) and

connectors (which are the communication vehicles among components). Component-and-connector

structures help answer questions such as What are the major executing

components and how do they interact? What are the major shared data stores?

Which parts of the system are replicated? How does data progress through the

system? What parts of the system can run in parallel? How can the system's

structure change as it executes?

Ōłæ

Allocation structures. Allocation structures show the

relationship between the software elements and the elements in one or more

external environments in which the software is created and executed. They

answer questions such as What processor does each software element execute on?

In what files is each element stored during development, testing, and system

building? What is the assignment of software elements to development teams?

These

three structures correspond to the three broad types of decision that

architectural design involves:

Ōłæ

How is the system to be structured as a set of code units

(modules)?

Ōłæ

How is the system to be structured as a set of elements that

have runtime behavior (components) and interactions (connectors)?

Ōłæ

How is the system to relate to nonsoftware structures in

its environment (i.e., CPUs, file systems, networks, development teams, etc.)?

SOFTWARE

STRUCTURES

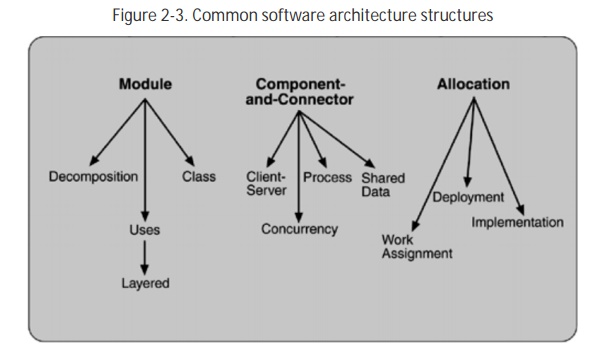

Some of

the most common and useful software structures are shown in Figure 2.3. These

are described in the following sections.

Module

Module-based structures include

the following.

Ōłæ

Decomposition.

The units are modules related to each other by the "is a submodule of

" relation, showing how larger modules are decomposed into smaller ones

recursively until they are small enough to be easily understood. Modules in

this structure represent a common starting point for design, as the architect

enumerates what the units of software will have to do and assigns each item to

a module for subsequent (more detailed) design and eventual implementation.

Modules often have associated products (i.e., interface specifications, code,

test plans, etc.). The decomposition structure provides a large part of the

system's modifiability, by ensuring that likely changes fall within the purview

of at most a few small modules. It is often used as the basis for the

development project's organization, including the structure of the

documentation, and its integration and test plans. The units in this structure

often have organization-specific names. Certain U.S. Department of Defense

standards, for instance, define Computer Software Configuration Items (CSCIs)

and Computer Software Components (CSCs), which are units of modular decomposition. In Chapter 15, we will see system function

groups and system functions as the units of decomposition.

Ōłæ

Uses.

The units of this important but overlooked structure are also modules, or (in

circumstances where a finer grain is warranted) procedures or resources on the

interfaces of modules. The units are related by the uses relation. One unit

uses another if the correctness of the first requires the presence of a correct

version (as opposed to a stub) of the second. The uses structure is used to

engineer systems that can be easily extended to add functionality or from which

useful functional subsets can be easily extracted.

Ōłæ

Layered.

When the uses relations in this structure are carefully controlled in a

particular way, a system of layers emerges, in which a layer is a coherent set

of related functionality. In a strictly layered structure, layer n may only use

the services of layer n ? 1. Many variations of this (and a lessening of this

structural restriction) occur in practice, however. Layers are often designed

as abstractions (virtual machines) that hide implementation specifics below

from the layers above, engendering portability. We will see layers in the case

studies of Chapters 3, 13 and 15.

Ōłæ

Class,

or generalization. The module units in this structure are called classes. The

relation is "inherits-from" or "is-an-instance-of." This

view supports reasoning about collections of similar behavior or capability

(i.e., the classes that other classes inherit from) and parameterized

differences which are captured by subclassing. The class structure allows us to

reason about re-use and the incremental addition of functionality.

Component-and-Connector

These structures include the

following.

Ōłæ

Process,

or communicating processes. Like all component-and-connector structures, this

one is orthogonal to the module-based structures and deals with the dynamic

aspects of a running system. The units here are processes or threads that are

connected with each other by communication, synchronization, and/or exclusion

operations. The relation in this (and in all component-and-connector

structures) isattachment, showing how the components and connectors are hooked

together. The process structure is important in helping to engineer a system's

execution performance and availability.

Ōłæ

Concurrency.

This component-and-connector structure allows the architect to determine

opportunities for parallelism and the locations where resource contention may

occur. The units are components and the connectors are "logical

threads." A logical thread is a sequence of computation that can be

allocated to a separate physical thread later in the design process. The

concurrency structure is used early in design to identify the requirements for

managing the issues associated with concurrent execution.

Ōłæ

Shared

data, or repository. This structure comprises components and connectors that

create, store, and access persistent data. If the system is in fact structured

around one or more shared data repositories, this structure is a good one to illuminate. It shows how data is produced and consumed by

runtime software elements, and it can be used to ensure good performance and

data integrity.

Ōłæ

Client-server.

If the system is built as a group of cooperating clients and servers, this is a

good component-and-connector structure to illuminate. The components are the

clients and servers, and the connectors are protocols and messages they share

to carry out the system's work. This is useful for separation of concerns

(supporting modifiability), for physical distribution, and for load balancing

(supporting runtime performance).

Allocation

Allocation structures include the

following.

Ōłæ

Deployment.

The deployment structure shows how software is assigned to hardware-processing

and communication elements. The elements are software (usually a process from a

component-and-connector view), hardware entities (processors), and

communication pathways. Relations are "allocated-to," showing on

which physical units the software elements reside, and "migrates-to,"

if the allocation is dynamic. This view allows an engineer to reason about

performance, data integrity, availability, and security. It is of particular

interest in distributed or parallel systems.

Ōłæ

Implementation.

This structure shows how software elements (usually modules) are mapped to the

file structure(s) in the system's development, integration, or configuration

control environments. This is critical for the management of development

activities and build processes.

Ōłæ

Work

assignment. This structure assigns responsibility for implementing and

integrating the modules to the appropriate development teams. Having a work

assignment structure as part of the architecture makes it clear that the

decision about who does the work has architectural as well as management

implications. The architect will know the expertise required on each team.

Also, on large multi-sourced distributed development projects, the work

assignment structure is the means for calling out units of functional

commonality and assigning them to a single team, rather than having them

implemented by everyone who needs them.

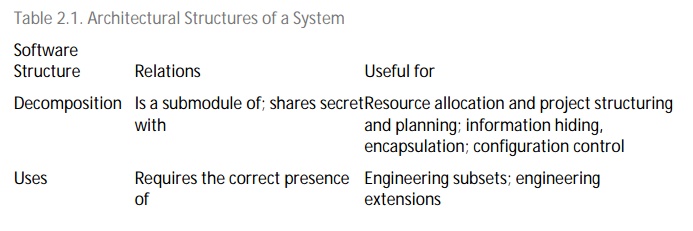

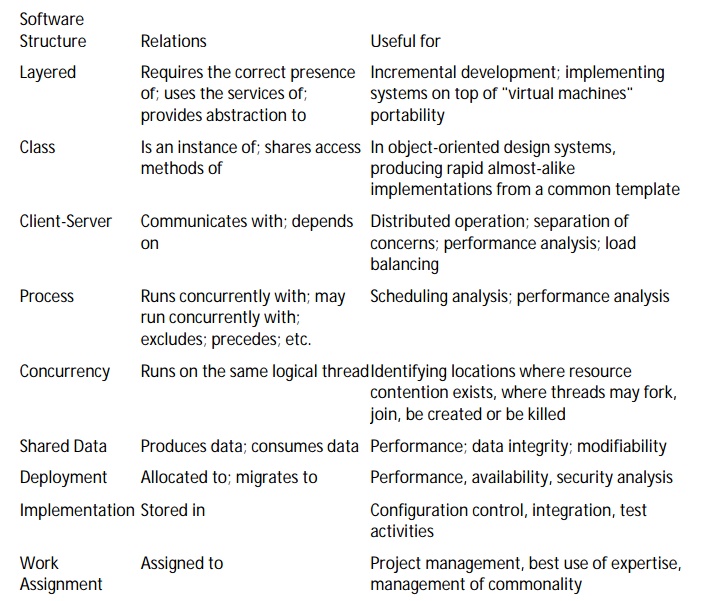

Table 2.1 summarizes the software

structures. The table lists the meaning of the elements and relations in each

structure and tells what each structure might be used for.

Although we often think about a

system's structure in terms of its functionality, there are system properties

in addition to functionality, such as physical distribution, process

communication, and synchronization, that must be considered at an architectural

level. Each structure provides a method for reasoning about some of the

relevant quality attributes. The uses structure, for instance, must be engineered

(not merely recorded) to build a system that can be easily extended or

contracted. The process structure is engineered to eliminate deadlock and

reduce bottlenecks. The module decomposition structure is engineered to produce

modifiable systems, and so forth. Each structure provides the architect with a

different view into the system and a different leverage point for design.

RELATING STRUCTURES TO EACH OTHER

Each of these structures provides

a different perspective and design handle on a system, and each is valid and

useful in its own right. Although the structures give different system

perspectives, they are not independent. Elements of one will be related to

elements of others, and we need to reason about these relations. For example, a

module in a decomposition structure may be manifested as one, as part of one,

or as several

components in one of the

component-and-connector structures, reflecting its runtime alter ego. In

general, mappings between structures are many to many.

Individual projects sometimes

consider one structure dominant and cast other structures, when possible, in

terms of it. Often, but not always, the dominant structure is module

decomposition. This is for a good reason: It tends to spawn the project

structure. Scenarios, described in Chapter 4, are useful for exercising a given

structure as well as its connections to other structures. For example, a

software engineer wanting to make a change to the client-server structure of a

system would need to consider the process and deployment views because

client-server mechanisms typically involve processes and threads, and physical

distribution might involve different control mechanisms than would be used if

the processes were colocated on a single machine. If control mechanisms need to

be changed, the module decomposition or layered view would need to be

considered to determine the extent of the changes.

Not all systems warrant

consideration of many architectural structures. The larger the system, the more

dramatic the differences between these structures tend to be; however, for

small systems we can often get by with less. Instead of working with each of

several component-and-connector structures, a single one will do. If there is

only one process, then the process structure collapses to a single node and

need not be carried through the design. If there is to be no distribution (that

is, if there is just one processor), then the deployment structure is trivial

and need not be considered further.

Structures represent the primary

engineering leverage points of an architecture. Individual structures bring

with them the power to manipulate one or more quality attributes. They

represent a powerful separation-of-concerns approach for creating the

architecture (and, later, for analyzing it and explaining it to stakeholders).

And, as we will see in Chapter 9, the structures that the architect has chosen

as engineering leverage points are also the primary candidates for the basis

for architecture documentation.

WHICH STRUCTURES TO CHOOSE?

We have briefly described a number

of useful architectural structures, and there are many more. Which ones should

an architect work on? Which ones should the architect document? Surely not all

of them.

There is no shortage of advice. In

1995, Philippe Kruchten [Kruchten 95] published a very influential paper in

which he described the concept of architecture comprising separate structures

and advised concentrating on four. To validate that the structures were not in

conflict with each other and together did in fact describe a system meeting its

requirements, Kruchten advised using key use cases as a check. This so-called

"Four Plus One" approach became popular and has now been

institutionalized as the conceptual basis of the Rational Unified Process.

Kruchten's four views follow:

Ōłæ

Logical.

The elements are "key abstractions," which are manifested in the

object-oriented world as objects or object classes. This is a module view.

Ōłæ

Process.

This view addresses concurrency and distribution of functionality. It is a component-and-connector

view.

Ōłæ

Development. This view shows the organization

of software modules, libraries, subsystems, and units of development. It is an

allocation view, mapping software to the development environment.

Ōłæ

Physical.

This view maps other elements onto processing and communication nodes and is

also an allocation view (which others call the deployment view).

At essentially the same time that

Kruchten published his work, Soni, Nord, and Hofmeister [Soni 95] published an

influential paper in which they reported the structures put into use across

many projects by the software architects in their organization. Their views

were conceptual, module interconnection, execution, and code. Once again, these

map clearly to the module, component-and-connector, and allocation models.

Other authors followed, and the

list of available structures grows ever more rich. Of course, you should not

use them all even though most of them will in fact exist in the system you are

building. Instead, consider that one of the obligations of the architect is to

understand how the various structures lead to quality attributes, and then

choose the ones that will best deliver those attributes. This point will be

treated at greater length in Chapter 9, on architectural representation.

ARCHITECTURAL

VIEW TYPES

Module Viewtype styles

ŌĆó

Decomposition

style

ŌĆó

Uses style

ŌĆó

Generalization

style

ŌĆó

Layered

style

Component and connector Viewtype

ŌĆó

Express

runtime behavior

ŌĆó

Described

in terms of connectors and components

ŌĆó

Objects,

processes, collection of objects are components

ŌĆó

Pipes,

repositories, sockets are connectors

ŌĆó

Middleware

is a connector Allocation Viewtype

ŌĆó

Maps

software units to elements of the environment(hardware, development team..)

ŌĆó

Deployment

style

ŌĆó

Implementation

style

Related Topics