Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiety Disorders: Traumatic Stress Disorders

Acute Stress Disorder

Acute Stress Disorder

Definition

It has long been recognized that clinically significant dissocia-tive

states are seen in the immediate aftermath of overwhelm-ing trauma. In

addition, many individuals may experience less clinically severe dissociative

symptoms or alterations of atten-tion and time sense. Because such syndromes,

even when short-lasting, can produce major disruption of everyday activities,

they may require clinical attention. During triage situations after a disaster,

it can be important to recognize this clinical picture, which may require

treatment intervention and which may also be predictive of later PTSD. As a

result of these considerations, a decision was made to include in DSM-IV a new

entity, acute stress disorder (ASD), grouped together with PTSD in the anxiety

disorders section. Essentially, it represents the clinical features of PTSD

along with conspicuous dissociative symptoms, of which at least three must be

present. The possible dissociative symptoms in ASD are a subjective sense of

numbing; detachment or absence of emotional response; reduced awareness of

one’s surroundings; derealization; depersonalization; and dissociative amnesia.

However, there is a lack of empirical evidence for some of the

assumptions inherent in the conceptualization of ASD, and there has been a call

for empirical evidence of acutely trau-matized individuals to address these

assumptions. The current emphasis placed on acute dissociative responses may be

flawed in that there are multiple pathways to PTSD, and most trauma survivors

who display severe acute stress reactions without dis-sociation can develop

PTSD.

Epidemiology

Little is known about the epidemiology of ASD as defined in DSM-IV, but

after events such as rape and criminal assault, the clinical picture of acute

PTSD is found in between 70 and 90% of individuals, although frequency of the

particular dissociative symptoms is unknown. One problem of most postdisaster

surveys is that they evaluate subjects at points several months or years after

the event. This makes any meaningful assessment of acute stress syndromes

difficult. One exception was the self-report-based assessment of morbidity 2

months after an earthquake in Ecuador, which found a 45% rate of caseness

(being a clinical case), with most prominent symptoms being fear, nervousness,

tenseness, worry, insomnia and fatigue (Lima et al., 1989).

Retrospective reports of acute stress symptoms should be interpreted cautiously because of the influence of current symptoms on recall of acute symptoms. In a longitudinal study evaluating report of acute stress symptoms at 1 month and 2 years post trauma, at least one of the four ASD diagnostic clus-ters was recalled inaccurately by 75% of patients (Harvey and Bryant, 2000).

Etiology

Little is known about the etiology of ASD specifically, but it is likely

that many of the same factors that apply to PTSD are rele-vant for ASD that is,

trauma intensity, preexisting psychopathol-ogy, family and genetic

vulnerability, abnormal personality, lack of social supports at the time of the

trauma and physical injury are all likely to increase vulnerability for ASD.

The role of acute arousal in the development of PTSD has been evaluated

in one study (Bryant et al., 2000).

Resting heart rate (HR) and ASD symptoms together were found to account for 36%

of the variance in PTSD prediction. Further, a formula using resting HR

following the trauma exposure (HR . 90 beats/ minute) and the diagnosis of ASD to predict PTSD development

possessed strong sensitivity (88%) and specificity (85%).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

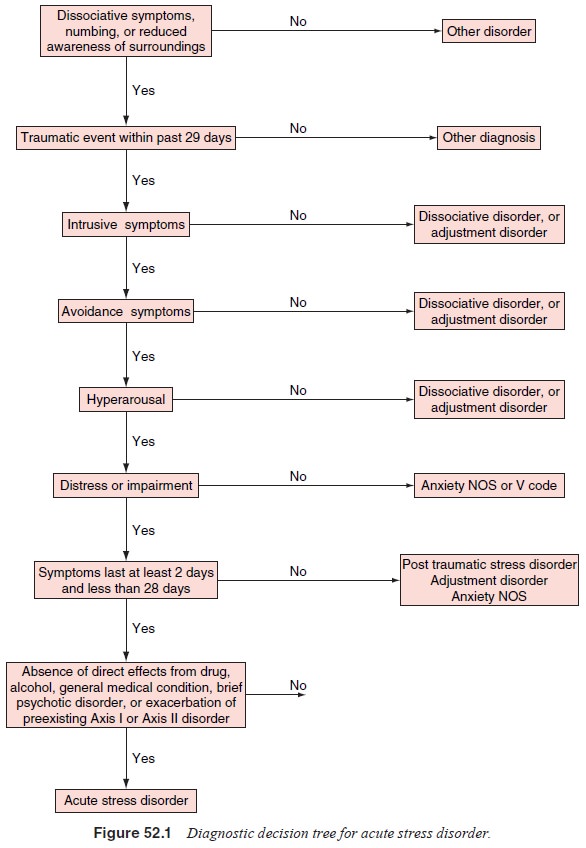

ASD may

need to be distinguished from several related disorders (Figure 52.1). Brief

psychotic disorder may be a more appropriate diagnosis if the predominant

symptoms are psychotic. It is possi-ble that major depressive disorder can

develop post traumaticallyand that there may be some

overlap with ASD, in which case both disorders are appropriately diagnosed.

When ASD-like symptoms are caused by direct physi-ological perturbation,

the symptoms may be more appropri-ately diagnosed with reference to the

etiological agent. Thus, an ASD-like picture that develops secondary to head

injury is more appropriately diagnosed as mental disorder due to a general

medical condition, whereas a clinical picture related to substance use (e.g.,

alcohol intoxication) is appropriately diagnosed as sub-stance-induced

disorder. Substance-related ASD is confined to the period of intoxication or

withdrawal. Head injury-induced ASD needs substantiating by evidence from the

history, physical examination and laboratory testing that the symptoms are a

di-rect physiological consequence of head trauma. Recently, a self-report scale

of ASD has been developed, the Acute Stress Disor-der Scale (ASDS). The scale

has demonstrated good test–retest reliability (r 5 0.94),

and in one sample (bushfire survivors), the ASDS predicted 91% of survivors who

developed PTSD and 93% of those who did not (Bryant et al., 2000).

Because ASD by definition cannot last longer than 1 month, if the

clinical picture persists, a diagnosis of PTSD is ap-propriate. Some increased symptoms

are expected in the great majority of subjects after exposure to major stress.

These remit in most cases and only reach the level of clinical diagnosis if

they are prolonged, exceed a tolerable quality, or interfere with everyday

function. Resolution may be more difficult if there has been previous

psychiatric morbidity, subsequent stress and lack of social support.

Course and Natural History

Although data do not exist on the course and natural history of ASD as

now defined, studies by Kooopman and coworkers (1994) indicated that

dissociative and cognitive symptoms, which are so common in the immediate wake

of trauma, improve sponta-neously with time. However, they also found that the

likelihood of developing PTSD symptoms at 7-month follow-up was more strongly

related to the occurrence of dissociative symptoms than to anxiety symptoms

immediately after exposure to the trauma. However, other studies have

questioned the dissociative criteria as critical for the prediction of later

PTSD.

Treatment

There are six general principles involved in administering any treatment

immediately after trauma. These include principles of brevity, immediacy, centrality,

expectancy, proximity and sim-plicity. That is, treatment of acute trauma is

generally aimed at being brief, provided immediately after the trauma whenever

possible, administered in a centralized and coordinated fashion with the

expectation of the person’s return to normal function and as proximately as

possible to the scene of the trauma, and not directed at any uncovering or

explorative procedures but rather at maintaining a superficial, reintegrating

approach.

People most highly at risk, and therefore perhaps most in need of

treatment, are as follows: survivors with psychiatric dis-orders; traumatically

bereaved people; children, especially when separated from their parents;

individuals who are particularly dependent on psychosocial supports, such as

the elderly, handi-capped and mentally retarded individuals; and traumatized

sur-vivors and body handlers.

Different components of treatment include providing information,

psychological support, crisis intervention and emotional first aid. Providing information

about the trauma is important as it can enable the survivor fully to recognize

and accept all the details of what happened. Information needs to be given in a

way that conveys hope and the possibility that psychological pain and threat of

loss may be coped with. Unrealistic hope needs to be balanced by the provision

of realistic explanations as to what happened. Psychological support helps to

strengthen coping mechanisms and promotes adaptive defenses. The survivor

benefits if he or she recognizes the need to take responsibility for a

successful outcome and is as actively involved with this as possible. Crisis

intervention is often used after disasters and acts of violence or other

serious traumas. It has been described by a number of investigators. Emotional

first aid has been described by Caplan (1984) using the six principles

presented earlier and is used to achieve any of the following: acceptance of

feelings, symptoms, reality and the need for help; recognition of

psychologically distressing issues; identification of available resources;

acceptance of responsibility and absence of blame; cultivation of an optimistic

attitude; and efforts to resume activities of daily life as much as possible.

Civilian trauma survivors with ASD were found to engage in the cognitive

strategies of punishment and worry more than survivors without ASD (Warda and

Bryant, 1998), and cogni-tive–behavioral therapy has been shown to reduce these

strate-gies and increase the use of reappraisal and social control strate-gies.

However, the relation of these findings to the development of PTSD has not yet

been determined.

There is little investigation as to whether early recogni-tion and

effective treatment of acute stress reactions prevent the development of PTSD,

although it is safe to assume that they are likely to have beneficial effects

in this regard. Nonetheless, as was recognized during World War II, rapid and

effective treat-ment of acute combat stress did not always prevent veterans

from developing subsequent chronicity. More recently, an intervention designed

to prevent the development of PTSD and administered in the acute phase,

critical incident stress debriefing, has been found to be ineffective in

preventing the development of PTSD. However, there has been an initial study

with motor vehicle ac-cident survivors that suggested exposure therapy and

exposure therapy with anxiety management training may be effective in

preventing PTSD (Bryant et al.,

1999).

Related Topics