Chapter: Medical Microbiology: An Introduction to Infectious Diseases: Actinomyces and Nocardia

Actinomycosis : Clinical Aspects

ACTINOMYCOSIS : CLINICAL ASPECTS

MANIFESTATIONS

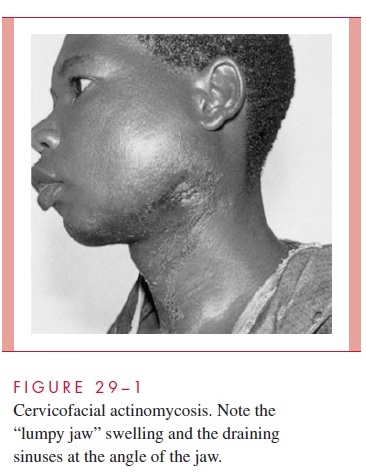

Actinomycosis exists in several forms that differ according to the original site and cir-cumstances of tissue invasion. Infection of the cervicofacial area, the most common site of actinomycosis (Fig 29 – 1), is usually related to poor dental hygiene, tooth extraction, or some other trauma to the mouth or jaw. Lesions in the submandibular region and the angle of the jaw give the face a swollen, indurated appearance.

Thoracic and abdominal actinomycoses are rare and follow aspiration or traumatic (including surgical) introduction of infected material leading to erosion through the pleura, chest, or abdominal wall. Diagnosis is usually delayed, because only vague or nonspecific symptoms are produced until a vital organ is eroded or obstructed. The firm, fibrous masses are often initially mistaken for a malignancy. Pelvic involvement as an ex-tension from other sites also occurs occasionally. It is particularly difficult to distinguish from other inflammatory conditions or malignancies. A more localized chronic en-dometritis, apparently caused by Actinomyces, has been associated with the use of in-trauterine contraceptive devices.

DIAGNOSIS

A clinical diagnosis of actinomycosis is based on the nature of the lesion, the slowly pro-gressive course, and a history of trauma or of a condition predisposing to mucosal inva-sion by Actinomyces. The etiologic diagnosis can be difficult to establish with certainty. Although the lesions may be extensive, the organisms in pus may be few and concen-trated in sulfur granule microcolonies deep in the indurated tissue. The diagnosis is fur-ther complicated by heavy colonization of the moist draining sinuses with other bacteria, usually Gram-negative rods. This contamination not only causes confusion regarding the etiology but interferes with isolation of the slow-growing anaerobicActinomyces. Mater-ial for direct smear and culture should include as much pus as possible to increase the chance of collecting the diagnostic sulfur granules.

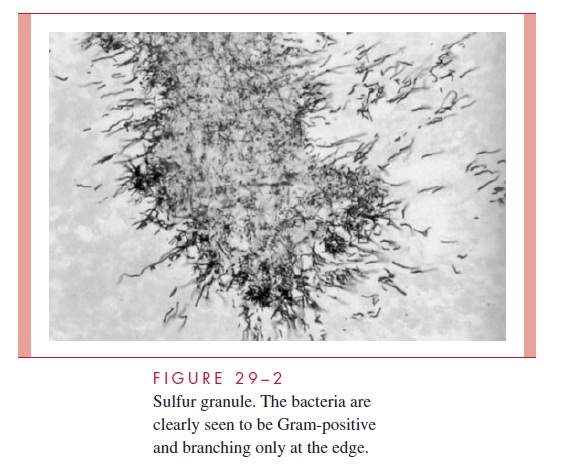

Sulfur granules crushed and stained show a dense, Gram-positive center with individ-ual branching rods at the periphery (Fig 29 – 2). Granules should also be selected for culture, because material randomly taken from a draining sinus usually grows only super-ficial contaminants. Culture media and techniques are the same as those used for other anaerobes. Incubation must be prolonged, because some strains require 7 days or more to appear. Identification requires a variety of biochemical tests to differentiateActinomyces from propionibacteria (anaerobic diphtheroids), which may show a tendency to form short branches in fluid culture.

Biopsies for culture and histopathology are useful, but it may be necessary to examine many sections and pieces of tissue before sulfur granule colonies of Actinomyces are found. The morphology of the sulfur granule in tissue is quite characteristic with routine hema-toxylin and eosin (HE) or histologic Gram staining. With HE, the edge of the granule shows amorphous eosinophilic “clubs” formed from the tissue elements and containing the branching actinomycotic filaments.

TREATMENT

Penicillin G is the treatment of choice for actinomycosis, although a number of other an-timicrobics (tetracycline, erythromycin, clindamycin) are active in vitro and have shown some clinical effectiveness. High doses of penicillin must be used and therapy prolonged for 4 to 6 weeks or longer before any response is seen. Although slow, response to ther-apy is often striking given the degree of fibrosis and deformity caused by the infection. Because detection of the causative organism is difficult, many patients are treated empiri-cally as a therapeutic trial based on clinical findings alone.

Related Topics