Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Behavior and Adaptive Functioning

Assessing Behavior and Adaptive Functioning in the Clinical Interview

Assessing Behavior and Adaptive

Functioning in the Clinical Interview

Finding out about a patient’s personality style, level of adaptive functioning and usual patterns of behavior is one of the major tasks of the psychiatric interview. A psychiatrist gains important infor-mation from what a patient and those people close to the patient say about her or his behavior. However, a psychiatrist also gains invaluable information by closely observing the person during the interview itself. Whether the psychiatrist is quickly sizing up an agitated patient during a psychiatric emergency or carefully noticing how a patient shifts in the chair during a psychotherapy session, the ability to observe a patient’s behavior is one of a psy-chiatrist’s most important tools. A patient’s appearance, attitude and motor behaviors during an interaction with the psychiatrist provide important clues to personality, capacity for interpersonal interactions and potentially problematic behavior patterns

Appearance

Observing a patient’s appearance includes making a judgment about the overall physical impression of the person reflected by grooming, clothing, poise and posture. The ability to appear well-kempt is impaired in many psychiatric disorders, ranging from the psychotic patient who appears disheveled after being up for several nights to the depressed patient dressed in dark, som-ber tones and slumped in the chair. Clothing often reveals aspectsof personality; patients with extroverted, histrionic, or dramatic personalities often wear brightly colored, unusual clothes and are often garishly made up. Problems with appearance can suggest the possibility of other functional impairments as well. The mo-tivation and degree of volitional control over appearance must usually be inferred. At times, appearance may provide an impor-tant clue of an inconsistency in a patient’s verbal presentation and suggest a serious behavior problem.

Attitude and Cooperation

The interviewer can also detect a patient’s

attitude and willing-ness to cooperate during an examination. Attitude and

coopera-tion are related but not identical concepts; a paranoid patient may

have a suspicious attitude but may cooperate by answer-ing the interviewer’s

questions nonetheless. Often, however, a person’s attitude and ability to

cooperate are both affected by psychiatric illness. Patients may be friendly or

hostile, seduc-tive, defensive, or apathetic. During the psychiatric interview,

they may seem attentive or disinterested and be frank or eva-sive and guarded.

Again, each of these attitudes and the degree of cooperation a patient exhibits

can depend on the underlying psychiatric state or can reflect a conscious

manipulation on the part of the patient for the sake of achieving a desired

goal. At-titude and degree of cooperativeness with an interviewer yield data

about a patient’s capacity to establish rapport and relate to others, thereby

suggesting the person’s general level of interper-sonal functioning.

Motor Behavior

The astute examiner can also observe motor

behaviors that pro-vide clues to a patient’s internal state. First, the overall

level of ac-tivity should be noted. Behavioral activity is often quantitatively

increased in patients with mania or anxiety disorders, whereas it may be

decreased in those with depression or intoxication. In addition, impulsivity

can sometimes be revealed by motor behav-iors, as when a person pounds on a

wall or hurls an object. Mo-tor behavior can also provide clues to personality;

the dramatic patient often gesticulates freely during conversation, whereas the

obsessive patient often conveys a sense of constricted facial movements and

gestures. The types of behaviors associated with overactivity may include

restlessness, pacing, handwringing, or other forms of agitation. In contrast,

psychomotor retardation is a slowing of the usual body movements. A depressed

patient with psychomotor slowing may be observed sitting perfectly still,

staring into space. Similarly, patients with underlying neurologi-cal disorders

such as Parkinson’s disease or those who are taking medicines that produce

parkinsonism may exhibit motor slowing in the form of lack of facial

expressiveness and loss of the body movements and gestures that often accompany

speech.

Another clinically relevant way of approaching the

task of assessing a patient’s behavior was suggested by Halleck (1994). He

suggested that in addition to focusing on appearance, atti-tude and cooperation

in the clinical evaluation, the interviewer can assess 1) the patient’s

physical and emotional attractiveness; 2) his or her means of seeking control

and whether control is a central issue; and 3) the degree to which the patient

is dependent, passive, aggressive, attention seeking, private, or exploitative

in his or her behaviors. Although patients with different styles have different

motives for and various ways of expressing these types of behaviors, examining

their behavior in each of these catego-ries is likely to provide a productive

additional approach to evalu-ating behavior and adaptive functioning.

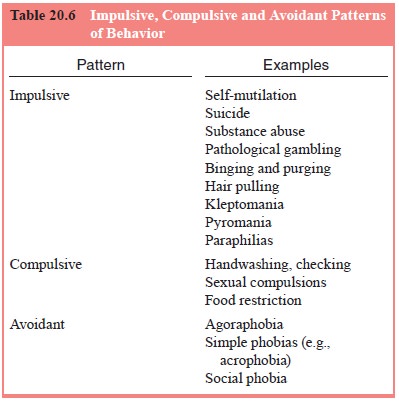

Problematic Patterns of Behavior

Problematic patterns of behavior, such as

impulsivity, compulsiv-ity and avoidance, cut across diagnostic groups; looking

for these patterns can be a fruitful way of characterizing aspects of

mal-adaptive functioning. Each of these three patterns can arise from a wide

array of psychiatric problems. For example, intoxicated people are often

disinhibited and impulsive, acting in ways that they would not act if they were

sober. However, a manic patient may also be impulsive, often spending money

freely or engaging in sexual activity without considering the consequences of

these actions. Labeling each of these patterns of behavior impulsive is an

important first step in reaching a diagnosis. In addition, finding one type of

impulsive behavior should prompt the psy-chiatrist to look for others and to

predict that the patient may act impulsively in the future.

Impulsive Behaviors

Impulsive behaviors are actions that arise without

much delay between the formation of an idea or desire and its gratification in

action. Not all impulsive behavior is pathological; in a muted and

well-modulated form, impulsivity is closer to spontaneity. Certain personality

styles, such as dramatic characters, are more likely to be spontaneous or

impulsive than others. In contrast, a person with a conscientious style might

decide to think about the purchase for a few days, then return to buy the

necklace only to find it gone.

However, in its more extreme forms, impulsivity is

often pathological. A number of behaviors that seem dissimilar may have

impulsivity as the common and uniting thread. Another advantage of thinking

about impulsivity as a distinct pattern of

problem behavior is that impulsivity in one sphere

is often ac-companied by impulsive behaviors in other arenas.

Behaviors that are frequently impulsive in nature

include self-mutilation and suicide, substance abuse, pathological gam-bling,

binging and purging eating behaviors, and hair pulling. In addition, urges to

steal (kleptomania), to set fires (pyromania), or to engage in sexually

perverse or unusual behaviors (paraphilias) also result in impulsive behaviors

(Table 20.6).

Different types of impulsive behaviors are often

experi-enced in similar ways by patients. One hallmark of impulsive acts is

that they are often preceded by a growing internal sense of tension and

discomfort that is reduced by the impulsive act itself. Whether the act is hair

pulling (trichotillomania) that results in baldness, or pathological gambling

that has severe financial consequences, the person is likely to feel that she

or he can no longer tolerate the internal tension and that giving in to the

impulse will provide relief to an uncomfortable internal state

A second characteristic of impulsive acts is that

they are often frankly pleasurable at the moment of action even if the per-son

is extremely remorseful afterward

A third hallmark of impulsive behaviors is that

patients are often relatively impervious to the consequences of their ac-tions

at the time and tend to underestimate their chances of being caught

Patients with impulsive patterns of behavior also

tend to underestimate the chances of being caught by a spouse or friend. In

addition, the impulsive nature of the action itself may increase the odds of

apprehension and punishment

Another feature common to impulsive behaviors is

that they often involve a binge, an episode of engaging in a behavior that

seems out of control and cannot be terminated by the patient. Often, the binge

ends only when an external constraint forces the patient to abandon the action.

An eating binge and the relapse of an alcoholic person are often similarly

described: “Once I started eating (drinking) I couldn’t stop. I just kept on

stuffing myself (ordering drinks) until I was too exhausted and sick (drunk and

broke) to continue”.

It is noteworthy that impulsively binging on a

substance such as alcohol sets the stage for further impulsive behaviors secondary

to intoxication.

Compulsive Behaviors

In its muted form, compulsivity can be seen as

careful-ness or attention to detail. It is easy to see how such attention to

detail is helpful in a variety of settings in daily life. Many jobs depend on

thoroughness and a willingness to keep working until the books are balanced to

the last penny. However, compul-sive behaviors become a problem when they begin

to consume much more time than necessary and when they are a response to

nonsensical thoughts (obsessions).

At first glance, compulsive patterns seem to be the oppo-site of impulsive patterns of behavior. In compulsive behaviors, a person repetitively behaves in a stereotyped way. Yet repeated impulsive behaviors can become difficult to distinguish from com-pulsive ones. Is a young female patient who repeatedly gives in to the urge to pull her hair out impulsive or compulsive or both?

In fact, there is evidence that impulsive and

compulsive behaviors tend to cooccur in the same individual. In one study,

impulsive aggression was found to be common in patients with

obsessive–compulsive disorder (Stein and Hollander, 1993). The authors

theorized that obsessive–compulsive disorder and impulsivity may both arise

from a similar problem in the self-regulation of behavior due to a

neuroanatomical lesion in the serotoninergic system. They found that treating

the obses-sive–compulsive disorder with serotonin reuptake inhibitors also

decreased these patients’ impulsive aggression.

The compulsions of obsessive–compulsive disorder, food-restricting behaviors such as those found in anorexia nervosa, and compulsive sexual behavior are common types of compul-sivity (see Table 20.6). Like impulsive behaviors, compulsions share common features and are experienced in similar ways by patients. However, the driving force behind compulsive behav-iors is not the gratification of impulses, but rather the prevention or reduction of anxiety and distress.

The concept that compulsive behavior is an attempt to reduce anxiety is easy to understand when the behavior is a re-sponse to an obsessive thought. However, even when the com-pulsive behavior is sexual in nature, it is driven by the need for anxiety reduction rather than by sexual desire (Coleman, 1992).

Avoidant Behaviors

As with impulsivity and compulsivity, avoidance in

its modulated form can be positive; learning from past negative ex-periences

and avoiding prior mistakes are important capacities.

Avoidant behaviors usually arise from a patient’s history of being fearful or concerned that he or she will become fearful in a given situation. Because of the past history or the perceived threat, the anxiety-provoking situation is avoided. Avoiding the situation means avoiding the fear and anxiety the situation threatens to produce

One study showed that fear and avoidance ratings

were highly correlated both at baseline level and after behavior therapy for

agoraphobia (Cox et al., 1993). In another

study, panic disorder patients with agoraphobia were differentiated from panic

disorder patients without agoraphobia by increased rates of anxiety-relevant

cognitions in the agoraphobic group (Ganellen et al., 1986).

Another feature common to avoidant behaviors is

that they become self-reinforcing and tend to worsen in severity over time if

left untreated.

A further common feature of avoidant behaviors is

their tendency to heighten anticipatory anxiety and precipitate the very

reactions that a person fears.

Related Topics