Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : Tissue Collection for Molecular Genetic Analysis

Tissue Collection for Molecular Genetic Analysis

Tissue Collection for Molecular Genetic

Analysis

Completion

of the Human Genome Project will soon result in the identification of more than

tens of thousands of new genes. Insight into the func-tion and complex

interaction of these genes is of more than just academic interest. Indeed, an

understanding of the molecular genetic under-pinning of human disease will

fundamentally change the practice of surgical pathology.

In the

past, a major role of the prosector was to submit well-fixed tissue sections

for traditional light microscopic examination. Toward this end, the routine

handling of specimens generally involved refrigeration for variable periods of

time, fixation in formalin or other denaturing solu-tions, sampling for

microscopic evaluation, and ultimate disposal of excess tissues. The role of

the prosector is clearly evolving. These changes will first affect research

hospitals, but the pace of change is so great that soon everyone practic-ing

surgical pathology will have to be familiar with tissue collection for

molecular genetic analy-sis. In this new era of functional genomics, there is a

new emphasis on rapid collection of fresh, unfixed tissues to optimize

preservation of un-degraded DNA and RNA for genomic studies. Toward this end,

handling of specimens now emphasizes prompt dissection, avoidance of formalin

and denaturing solutions, multiplex processing for diverse diagnostic assays,

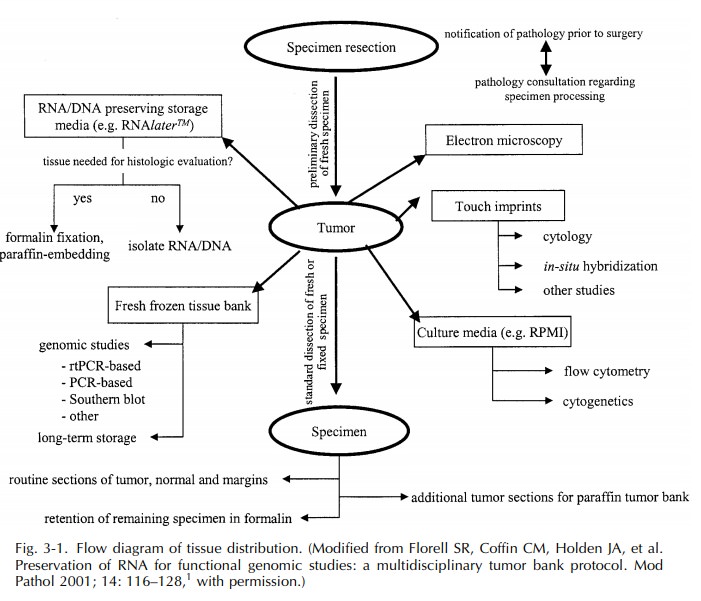

and long-term storage of excess fresh tissues. A flow diagram for the

increasingly complex and ever-evolving nature of tissue distribution is shown

in Figure 3–1.

The bane

of genomic studies is the degrada-tion of RNA and DNA, and thus the major aim

when securing tissue is to do so as quickly as possible. Degradation of DNA and

RNA begins at the moment the blood supply to a tissue has been interrupted.

Therefore, rapid tissue collec-tion involves a coordinated network that begins

with punctual delivery of specimens from the operating room to the pathology

laboratory and ends with prompt processing of the specimen in the surgical

pathology suite. The time allowed from surgical resection to specimen

processing depends on a host of factors, but as a rule of thumb: the faster the better. In busy surgical

pathol-ogy laboratories, rapid tissue collection requires prioritization of

specimens potentially requiring molecular genetic evaluation over specimens

that do not. Hence, be on the lookout for hematopoi-etic tumors and primitive

tumors (i.e., “small round blue cell tumors”) of children and young adults, as

the molecular genetic profile of these tumors already plays a central role in

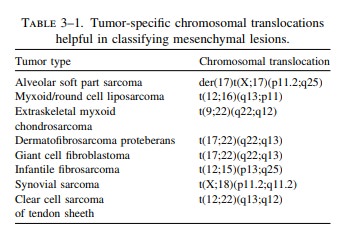

tumor char-acterization and patient treatment. Chromosome analysis, molecular

cytogenetics, and molecular assays are becoming increasingly useful in the

diagnosis of other tumors as well. Table 3–1 pro-vides a partial list of

heterogeneous mesenchymal lesions where the identification of certain specific

chromosomal translocations now permits more thorough and accurate

classification. If any one of these lesions is considered in the differential

diagnosis, the specimen should be targeted for rapid tissue collection.

The

optimal way to process tissues for molecu-lar genetic studies obviously depends

on the nature and methodology of the analysis. Flow cytometry, cytogenetics,

and other studies that entail the growth of living cell cultures require fresh

sterile tissue samples. These samples should be collected as 0.5- to 1.0-cm

cubes of tissue. A balanced physiologic solution such as Roswell Park Memorial

Institute (RPMI) medium serves as an excellent medium for short-term storage

and

Although various methods are being developed to optimize DNA and RNA

ex-traction from formalin-fixed tissues, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based

techniques looking for DNA and RNA alterations are best performed on fresh,

unfixed tissues. This tissue can be snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored

for long peri-ods at 2808C. Advances are being made in the development

of more versatile tissue media (e.g., RNAlaterTM) that

preserve the integrity of DNA and RNA for molecular analysis and at the same

time maintain the histologic and immunohisto-chemical properties of the tissue.

Remember that PCR-based techniques are highly sensitive for detecting rare

abnormal cells among large num-bers of normal cells. Careful attention to

cleanli-ness, such as the use of fresh cutting utensils and changing gloves

between specimens, is therefore critical if one is to avoid the effects of

speci-men contamination.

Given

the breakneck pace at which genomic studies are finding increasing diagnostic

and therapeutic applications, it is often prudent to store excess fresh tissue

in a repository should it be needed for future analysis. This need to collect,

store, process, and distribute well-characterized human tissues for diagnostic

and investigative purposes has resulted in the emergence oftissue banks. Unlike traditional archival bankswhere the tissues

are stored as formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded blocks, the tissues in

tissue banks are generally stored at 2808C in an unpro-cessed state or as pellets of

extracted DNA or RNA.

Not only

may these banked fresh frozen tissues be utilized for present and future

diagnostic stud-ies, they are of considerable value as resources for molecular

genetic translational research. A few guidelines should be kept in mind when

collecting and distributing tissues for investi-gative purposes. First, the

pathology laboratory should not distribute tissue for research purposes without

prior documentation of approval from the local Institutional Review Board

(IRB). IRBs have been established to define the obligations of researchers and

to ensure that the use of human tissues conform to federal regulations. Second,

patient care must always come first. There may be instances when it is simply

not possible to submit tissues for investigative studies without compromising

your ability to optimize patient care. In the case of limited specimens (e.g.,

biops-ies), there may not be enough tissue to support microscopic examination

and research studies; and for anatomically complex specimens, where it is vital

to maintain the integrity of the specimen for proper orientation and evaluation

of margins, it may not be prudent to violate the specimen to obtain fresh

tissue when formalin fixation is necessary. What ever the scenario, whenever

patient care collides with basic science require-ments, patient care must win.

Molecular

genetic analysis of human tissues is a constantly changing field. New and

exciting techniques are being developed every day. Surgi-cal pathology

prosectors familiar with the latest developments in molecular diagnoses are

best prepared to handle resected and biopsied tis-sues appropriately.

Related Topics