History - The Tughlaq Dynasty | 11th History : Chapter 10 : Advent of Arabs and turks

Chapter: 11th History : Chapter 10 : Advent of Arabs and turks

The Tughlaq Dynasty

The Tughlaq Dynasty

Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq (1320–1324)

Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq followed a policy of reconciliation with the nobles. But in the fifth year of his reign (1325) Ghiyas-ud-din died. Three days later Jauna ascended the throne and took the title Muhammad bin Tughlaq.

Muhammad Bin Tughlaq (1324-1351)

Muhammad Tughlaq was a learned, cultured and talented prince but gained a reputation of being merciless, cruel and unjust. Muhammad Tughlaq effectively repulsed the Mongol army that had marched up to Meerut near Delhi. Muhammad was an innovator. But he, unlike Ala-ud-din, lacked the will to execute his plans successfully.

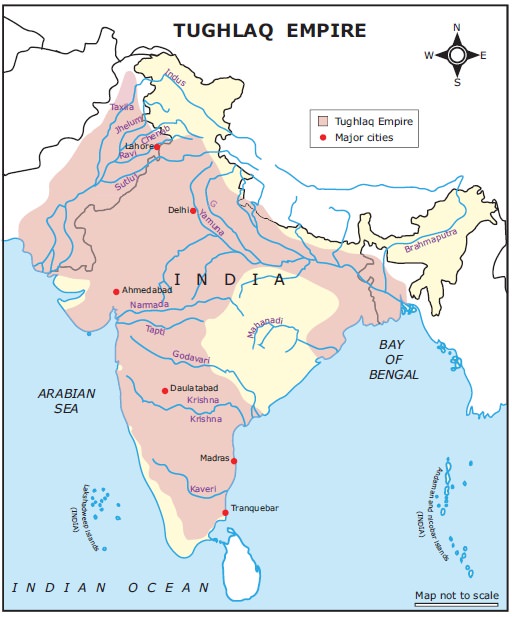

Transfer of Capital

Muhammad Tughlaq’s attempt to shift the capital from Delhi to Devagiri in Maharashtra, which he named Daulatabad, was a bold initiative. This was after his realization that it was difficult to rule south India form Delhi. Centrally located, Devagiri also had the advantage of possessing a strong fort atop a rocky hill. Counting on the military and political advantages, the Sultan ordered important officers and leading men including many Sufi saints to shift to Devagiri. However, the plan failed, and soon Muhammad realised that it was difficult to rule North India from Daulatabad. He again ordered transfer of capital back to Delhi.

Token Currency

The next important experiment of Muhammad was the introduction of token currency. This currency system had already been experimented in China and Iran. For India it was much ahead of its time, given that it was a time when coins were based on silver content.

When Muhammad issued bronze coins, fake coins were minted which could not be prevented by the government. The new coins were devalued to such an extent that the government had to withdraw the bronze coins and replace them with silver coins, which told heavily on the resources of the empire.

Sultan’s Other Innovative Measures

Equally innovative was Muhammad Tughlaq's scheme to expand cultivation. But it also failed miserably. It coincided with a prolonged and severe famine in the Doab. The peasants who rebelled were harshly dealt with. The famine was linked to the oppressive and arbitrary collection of land revenue. The Sultan established a separate department (Diwan-i-Amir Kohi) to take care of agriculture. Loans were advanced to farmers for purchase of cattle, seeds and digging of wells but to no avail. Officers appointed to monitor the crops were not efficient; the nobility and important officials were of diverse background. Besides, the Sultan’s temperament had also earned him a lot of enemies.

Ala-ud-din Khalji had not annexed distant territories knowing full well that they could not be effectively governed. He preferred to establish his suzerainty over them. But Muhammad annexed all the lands he conquered. Therefore, at the end of his reign, while he faced a series of rebellions, his repressive measures further alienated his subjects. Distant regions like Bengal, Madurai, Warangal, Awadh, Gujarat and Sind hoisted the flags of rebellion and the Sultan spent his last days fighting rebels. While he was frantically engaged in pursuing a rebel leader in Gujarat, he fell ill, and died at the end of his 26thregnal year (1351).

Firuz Tughlaq (1351–1388)

Firuz’sfather,Rajab,wastheyoungerbrother of Ghiyas-ud-din Tughlaq. Both had come from Khurasan during the reign of Ala-ud-din Khalji. Rajab who had married a Jat princess had died when Firuz was seven years old. When Ghiyas-ud-din ascended the throne, he gave Firuz command of a 12,000 strong cavalry force. Later Firuz was made in charge of one of the four divisions of the Sultanate. Muhammad bin Tughlaq died without naming his successor. The claim made by Muhammad’s sister to his son was not supported by the nobles. His son, recommended by Muhammad’s friend Khan-i Jahan, was a mere child. Under such circumstances, Firuz ascended the throne.

Conciliatory Policy towards Nobles

Firuz Tughlaq followed a conciliatory policy towards the nobles and theologians. Firuz restored the property of the owners who had been deprived of it during the reign of Muhammad Tughlaq. He reintroduced the system of hereditary appointments to offices, a practice which was not favoured by Ala-ud-din Khalji. The Sultan increased the salaries of government officials. While toning up the revenue administration, he reduced several taxes. He abolished many varieties of torture employed by his predecessor. Firuz had a genuine concern for the slaves and established a separate government department to attend to their welfare. The slave department took care of the wellbeing of 180,000 slaves. They were trained in handicrafts and employed in the royal workshops.

Firuz Policy of No Wars

Firuz waged no wars of annexation, though he was not averse to putting down rebellions challenging his authority. There were only two Mongol incursions during his times, and both of them were successfully repulsed. His Bengal campaign to put down a rebellion there, however, was an exception. His army slew thousands and his entry into Odisha on his way helped him extract the promise of tribute from the Raja. A major military campaign of his period was against Sind (1362). He succeeded in routing the enemies on the way. Yet his enemies and a famine that broke out during this period gave Sultan and his army a trying time. Firuz's army, however, managed to reach Sind. The ruler of Sind agreed to surrender and pay tribute to the Sultan.

Religious Policy

Firuz favoured orthodox Islam. He proclaimed his state to be an Islamic state largely to satisfy the theologians. Heretics were persecuted, and practices considered un-Islamic were banned. He imposed jizya, head tax on non-Muslims, which even the Brahmins were compelled to pay. Yet Firuz did not prohibit the building of new Hindu temples and shrines. His cultural interest led to translation of many Sanskrit works relating to religion, medicine and music. As an accomplished scholar himself, Firuz was a liberal patron of the learned including non-Islamic scholars. Fond of music, he is credited with establishing several educational institutions and a number of mosques, palaces and forts.

Public Works

Firuz undertook many irrigation projects. A canal he dug from Sutlej river to Hansi and another canal in Jumna indicate his sound policy of public works development.

Firuz died in 1388, after making his son Fath Khan and grandson Ghiyas-ud-din as joint rulers of Delhi Sultanate.

The principle of heredity permitted for the nobles and applied to the army weakened the Delhi Sultanate. The nobility that had regained power got involved in political intrigues which undermined the stability of the Sultanate. Within six years of Firuz Tughlaq’s death four rulers succeeded him.

Timur’s Invasion

The last Tughlaq ruler was Nasir-ud-din Muhammad Shah (1394–1412), whose reign witnessed the invasion of Timur from Central Asia.Turkish Timur,who could claim a blood relationship with the 12thcentury great Mongol Chengiz Khan, ransacked Delhi virtually without any opposition. On hearing the news of arrival of Timur, Sultan Nasir-ud-din fled Delhi.

Timur also took Indian artisans such as masons, stone cutters, carpenters whom he engaged for raising buildings in his capital Samarkhand. Nasir-ud-din managed to rule up to 1412. Then the Sayyid and Lodi dynasties ruled the declining empire from Delhi till 1526.

Related Topics