Chapter: Basic & Clinical Pharmacology : Rational Prescribing & Prescription Writing

The Prescription

THE PRESCRIPTION

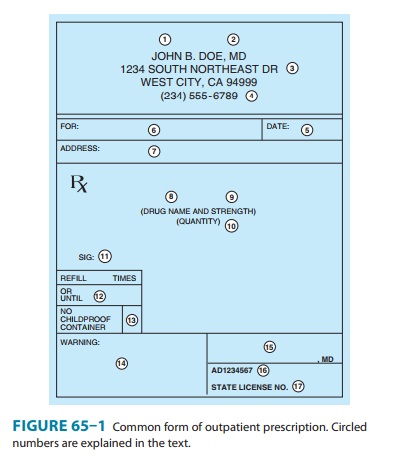

Although a

prescription can be written on any piece of paper (as long as all of the legal

elements are present), it usually takes a specific form. A typical printed

prescription form for outpatients is shown in Figure 65–1.

In the hospital

setting, drugs are prescribed on a particular page of the patient’s hospital

chart called the physician’s order

sheet(POS) or chart order. The

contents of that prescription arespecified in the medical staff rules by the

hospital’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee. The patient’s name is typed or

written on the form; therefore, the orders consist of the name and strength of

the medication, the dose, the route and frequency of adminis-tration, the date,

other pertinent information, and the signature of the prescriber. If the

duration of therapy or the number of doses is not specified (which is often the

case), the medication is contin-ued until the prescriber discontinues the order

or until it is termi-nated as a matter of policy routine, eg, a stop-order

policy.

A typical chart order

might be as follows:

11/15/08

10:30 a.m.

(1)

Ampicillin 500 mg IV

q6h × 5 days

(2) Aspirin 0.6 g per rectum q6h prn temp over 101 [Signed]

Janet B. Doe, MD

Thus, the elements of

the hospital chart order are equivalent to the central elements (5, 8–11, 15)

of the outpatient prescription.

Elements of the Prescription

The first four elements

(see circled numerals in Figure 65–1) of the outpatient prescription establish

the identity of the prescriber: name, license classification (ie, professional

degree), address, and office telephone number. Before dispensing a

prescription, the pharmacist must establish the prescriber’s bona fides and

should be able to contact the prescriber by telephone if any questions arise.

Element [5] is the date on which the prescription was writ-ten. It should be

near the top of the prescription form or at the beginning (left margin) of the

chart order. Since the order has legal significance and usually has some

temporal relationship to the date of the patient-prescriber interview, a

pharmacist should refuse to fill a prescription without verification by telephone

if too much time has elapsed since its writing.Elements [6] and [7] identify

the patient by name and address.The patient’s name and full address should be

clearly spelled out.

The body of the

prescription contains the elements [8] to [11] that specify the medication, the

strength and quantity to be dispensed, the dosage, and complete directions for

use. When writing the drug name (element [8]), either the brand name

(proprietary name) or the generic name (nonproprietary name) may be used.

Reasons for using one or the other are discussed below. The strength of the

medication [9] should be written in metric units. However, the prescriber

should be familiar with bothsystems now in use: metric and apothecary. For

practical purposes, the following approximate conversions are useful:

1 grain (gr) = 0.065 grams

(g), often rounded

to 60 milligrams (mg)

15 gr = 1 g

1 ounce (oz) by volume = 30 milliliters (mL)

1 teaspoonful (tsp) = 5 mL

1 tablespoonful (tbsp) = 15 mL

1 quart (qt) = 1000 mL

1 minim = 1 drop (gtt)

20 drops = 1 mL

2.2 pounds (lb) = 1

kilogram (kg)

The

strength of a solution is usually expressed as the quantity of solute in

sufficient solvent to make 100 mL; for instance, 20% potassium chloride

solution is 20 grams of KCl per deciliter (g/dL) of final solution. Both the

concentration and the volume should be explicitly written out.

The

quantity of medication prescribed should reflect the anticipated duration of

therapy, the cost, the need for continued contact with the clinic or physician,

the potential for abuse, and the potential for toxicity or overdose.

Consideration should be given also to the standard sizes in which the product

is available and whether this is the initial prescription of the drug or a

repeat prescription or refill. If 10 days of therapy are required to

effec-tively cure a streptococcal infection, an appropriate quantity for the

full course should be prescribed. Birth control pills are often prescribed for

1 year or until the next examination is due; how-ever, some patients may not be

able to afford a year’s supply at one time; therefore, a 3-month supply might

be ordered, with refill instructions to renew three times or for 1 year

(element [12]). Some third-party (insurance) plans limit the amount of medicine

that can be dispensed—often to only a month’s supply. Finally, when first

prescribing medications that are to be used for the treat-ment of a chronic

disease, the initial quantity should be small, with refills for larger

quantities. The purpose of beginning treat-ment with a small quantity of drug

is to reduce the cost if the patient cannot tolerate it. Once it is determined

that intolerance is not a problem, a larger quantity purchased less frequently

is sometimes less expensive.

The directions for use

(element [11]) must be both drug-specific and patient-specific. The simpler the

directions, the better; and the fewer the number of doses (and drugs) per day,

the better. Patient noncompliance (also known as nonadherence, failure to

adhere to the drug regimen) is a major cause of treatment failure. To help

patients remember to take their medications, prescribers often give an

instruction that medications be taken at or around mealtimes and at bedtime.

However, it is important to inquire about the patient’s eating habits and other

lifestyle patterns, because many patients do not eat three regularly spaced

meals a day.

The

instructions on how and when to take medications, the duration of therapy, and

the purpose of the medication must be explained to each patient both by the

prescriber and by the phar-macist. (Neither should assume that the other will

do it.)

Furthermore, the drug

name, the purpose for which it is given, and the duration of therapy should be

written on each label so that the drug may be identified easily in case of

overdose. An instruction to “take as directed” may save the time it takes to

write the orders out but often leads to noncompliance, patient confusion, and

medica-tion error. The directions for use must be clear and concise to prevent

toxicity and to obtain the greatest benefits from therapy.

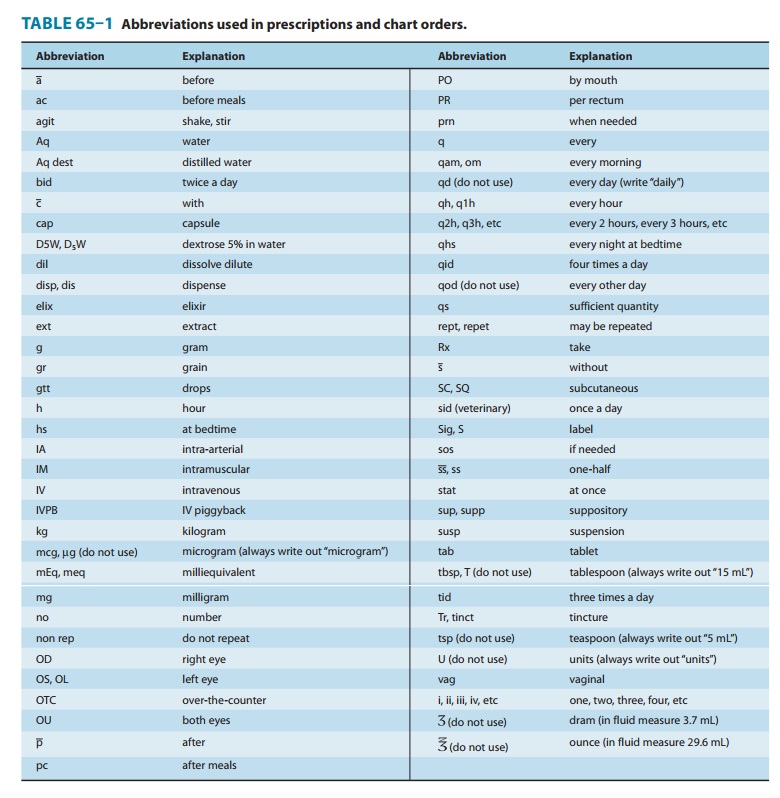

Although directions

for use are no longer written in Latin, many Latin apothecary abbreviations

(and some others included below) are still in use. Knowledge of these

abbreviations is essential for the dispensing pharmacist and often useful for

the prescriber. Some of the abbreviations still used are listed in Table 65–1.

Note: It is always

safer to write out the direction without abbreviating.

Elements [12] to [14]

of the prescription include refill infor-mation, waiver of the requirement for

childproof containers, and additional labeling instructions (eg, warnings such

as “may cause drowsiness,” “do not drink alcohol”). Pharmacists put the name of

the medication on the label unless directed otherwise by the pre-scriber, and

some medications have the name of the drug stamped or imprinted on the tablet

or capsule. Pharmacists must place the expiration date for the drug on the

label. If the patient or pre-scriber does not request waiver of childproof containers,

the phar-macist or dispenser must place the medication in such a container.

Pharmacists may not refill a prescription medication without authorization from

the prescriber. Prescribers may grant authori-zation to renew prescriptions at

the time of writing the prescrip-tion or over the telephone. Elements [15] to

[17] are the prescriber’s signature and other identification data.

Related Topics