Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Substance Abuse: Phencycline Use Disorders

Substance Abuse: Phencycline Use Disorders

Substance Abuse: Phencycline Use Disorders

Phencyclidine (PCP) failed its development as a

potential general anesthetic agent during the 1950s because of its propensity

to cause psychotic episodes during emergence that were sometimes severe and

violent, and lasted from hours to days. PCP psychosis closely resembles

schizophrenia in terms of symptoms, signs and thought disorder. A single very

small dose of PCP given to a normal sub-ject induces a psychotic state lasting

for several hours, while in a person with schizophernia, the psychosis can be exacerbated

for several weeks by the fact that it is easy to synthesize. Many users

consumed PCP on a daily or near-daily basis for weeks or months at a time.

There were numerous instances of severe medical toxicity, a number of deaths

from overdoses, and many cases of prolonged (up to six weeks) psychoses in

users without preexisting psychotic disorders. In addition to CNS effects, PCP

overdose involves sym-pathomimetic, neuromuscular and renal effects that can

result in tis-sue damage and death. These problems are compounded by PCP’s

lipophilicity, long half-life and still longer duration of action. The

incidence and prevalence of PCP abuse have declined markedly since the late

1970s to early 1980s; however, PCP abuse continues and remains relatively high

in certain areas of the USA. PCP exerts its characteristic effects by

noncompetitive blockade of the N-me-thyl D-aspartate class of glutamate

receptors. Ketmine is a PCP de-rivative that shares PCP’s mechanism of action

and is approved for general effects are less frequent and severe owing to the

lower po-tency and shorter duration of ketamine action compared with PCP.

Epidemiology

As of the year 2000, the highest rates of PCP use

during the previous year were observed among 18- to 20-year-olds, followed by 12-

to 17-, 21- to 25-, and 26- to 34-year-olds. In 2000, among Americans aged 12

or older, it was estimated that 54 000 had used PCP within the previous month,

264 000 within the previous year and 5 693 000 (2% of the population) within

their lifetimes (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,

2001). In the same year, PCP ranked 31st among the top 50 drugs mentioned most

frequently in drug-related emergency department episodes nationwide show-ing a

48% increase in ER mentions compared with 1999 (Substance Abuse and Mental

Health Services Administration, 2002).

In 1983, more than 66% of PCP-related deaths

reported to the Drug Abuse Warning Network involved at least another one drug.

Many of the PCP-related deaths were not the result of overdose or drug

interaction or reaction, but the direct result of some external

event facilitated by intoxication (e.g., homicides,

accidents). The various manners of death (such as drowning and being shot by

police) reported are consistent with the disorientation and violent aggressive

behavior that can be stimulated by PCP (Crider, 1986).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The effects of low-dose PCP administration have

been extensively studied in volunteers. In normal subjects single intravenous

doses of 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg induced withdrawal, negativism and in some cases

catatonic posturing; thinking processes became concrete, idiosyn-cratic and

bizarre in the absence of significant physical or neurologi-cal findings; and

drug effects persisted for 4 to 6 hours In contrast to lysergic acid

diethylamide (LSD) or amphetamine PCP was noted to induce disturbances in

symbolic thinking perception and attention strikingly similar to those observed

in schizophrenia. Administra-tion of PCP to schizophrenic subjects caused

exacerbation of ill-ness-specific symptoms persisting up to several weeks,

suggesting that schizophrenic or preschizophrenic individuals may be at

sig-nificantly increased risk of behavioral effects from PCP abuse.

Phenomenology and Variations in Presentation

Physicians must be alert to the wide spectrum of

PCP effects on multiple organ systems. Because fluctuations in serum levels may

occur unpredictably, a patient being treated for apparently selective

psychiatric or behavioral complications of PCP abuse may suddenly undergo

radical alterations in medical status; emergency medi-cal intervention may

become necessary to avoid permanent organ damage or death. Any patient

manifesting significant cardiovascu-lar, respiratory, neurological, or

metabolic derangement subsequent to PCP use should be evaluated and treated in

a medical service; the psychiatrist plays a secondary role in diagnosis and

treatment until physiological stability has been reached and sustained.

PCP-intoxicated patients may come to medical

attention on the basis of alterations in mental status; bizarre or violent

be-havior; injuries sustained while intoxicated; or medical complica-tions,

such as rhabdomyolysis, hyperthermia, or seizures (Bald-ridge and Bessen,

1990). As illicit ketamine use has increased significantly as part of the “club

drug” phenomenon, it is impor-tant to remember that ketamine can induce the

same spectrum of effects and complications, the chief difference from PCP being

the much shorter duration of action of ketamine.

Studies of normal volunteers suggested that the

acute psy-chosis induced by a single low dose of PCP usually lasts for 4 to 6

hours (Javitt and Zukin, 1991). However, in some PCP users psy-chotic symptoms

including hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, thought disorder and catatonia,

with intact consciousness, have been reported to persist from days to weeks

after single doses. Sudden and impulsive violent and assaultive behaviors have

been reported in PCP-intoxicated patients without previous histories of such

conduct.

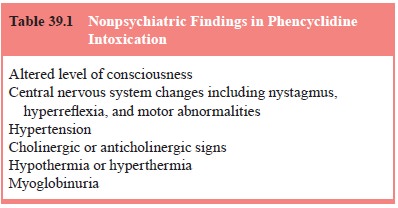

In PCP intoxication, the central nervous, cardiovascular, respiratory and peripheral autonomic systems are affected to de-grees ranging from mild to catastrophic (Table 39.1). The level of consciousness may vary from full alertness to coma. Coma of variable duration may occur spontaneously or after an episode of bizarre or violent behavior Nystagmus (which may be horizontal, vertical, or rota-tory) has been described in 57% of a series of 1 000 patients (McCarron et al., 1981). Consequences of PCP-induced central nervous system hyperexcitability may range from mildly in-creased deep tendon reflexes to grand mal seizures (observed in 31 of a series of 1 000 PCP-intoxicated patients) or status epilep-ticus (McCarron et al., 1981; Kessler et al., 1974). Seizures are usually generalized, but focal seizures or neurological deficits have been reported, probably on the basis of focal cerebral vaso-constriction (Crosley and Binet, 1979). Other motor signs have been observed, such as generalized rigidity, localized dystonias, facial grimacing and athetosis.

Hypertension, one of the most frequent physical

findings, was described in 57% of 1 000 patients evaluated, and it was found to

be usually mild and self-limiting, but 4% had severe hypertension, and some

remained hypertensive for days (McCarron et

al., 1981). Tachycardia occurs in 30% of patients. PCP-induced tachypnea can progress to periodic

breathing and respiratory arrest (Hurlbut, 1991). Autonomic signs seen in PCP

intoxication may be cholinergic (diaphoresis, bronchospasm, miosis, salivation,

bronchorrhea) or anticholinergic (mydriasis, urinary retention). Hypothermia

and hyperthermia have been observed (McCarron et al., 1981). Hyperthermia may reach malignant proportions (Thompson, 1979). Rhabdomyolysis

frequently results from a combination of PCP-induced muscle contractions and

trauma occurring in relation to injuries sustained as a result of behavioral

effects. Acute renal failure can result from myoglobinuria.

Assessment

Special Issues in Psychiatric Examination and History

The disruption of normal cognitive and memory

function by PCP frequently renders patients unable to give an accurate history.

Therefore, assay of urine or blood for drugs may be the only way to establish

the diagnosis. PCP is frequently taken in forms in which it has been used to

adulterate other drugs, such as mari-juana and cocaine, often without the

user’s knowledge. One of the most recent and alarming manifestations of this

phenomenon is a preparation known variously as “illy”, “hydro”, “wet”, or

“fry”, consisting of a marijuana cigarette or blunt containing

formalde-hyde/formalin (which is advertised) and PCP (which often is not). By

disrupting sensory pathways, PCP frequently renders users hypersensitive to

environmental stimuli to the extent that physi-cal examination or psychiatric

interview may cause severe agita-tion. If PCP intoxication is suspected,

measures should be taken from the outset to minimize sensory input. The patient

should be evaluated in a quiet, darkened room with the minimal necessary number

of medical staff present. Assessments may need to be interrupted periodically.

Relevant Physical Examination and Laboratory Findings

Vital signs should be obtained immediately on presentation.

Temperature, blood pressure and respiratory rate are dose-dependently increased

by PCP and may be of a magnitude requiring emergency medical treatment to avoid

the potentially fatal complications of malignant hyperthermia, hypertensive

cri-sis and respiratory arrest. In all cases, monitoring of vital signs should

continue at 2- to 4-hour intervals throughout treatment, because serum PCP

levels may increase spontaneously as a re-sult of mobilization of drug from

lipid stores or enterohepatic recirculation. Analgesic and behavioral changes

induced by PCP not only predispose patients to physical injury but also mask

these injuries, which may be found only with careful physical examination.

Because PCP is usually supplied in combination with

other drugs and is often misrepresented, toxicological analysis of urine or

blood is essential. However there may be circumstances in which PCP may not be

detected in urine even if it is present in the body, for example, when the

urine is alkaline. On the other hand, in chronic PCP users, drug may be

detected in urine up to 30 days after last use (Simpson et al., 1982–1983). It must be kept in mind that false-positive PCP

results can be caused by the presence of venlafaxine and O-desmethylvenlafaxine (Sena et

al., 2002), or dextromethorphan (Shier, 2000). Urine should be tested for

heme because of the possible complication of myoglobinuria.

Differential Diagnosis

The presence of nystagmus and hypertension with

mental status changes should raise the possibility of PCP intoxication. Because

of the close resemblance of both the acute and the prolonged forms of PCP

psychosis to schizophrenia, and the increased sen-sitivity of patients with

schizophrenia to the psychotomimetic ef-fects of the drug, an underlying

schizophrenia spectrum disorder should be considered, particularly if paranoia

or thought disorder persists beyond 4 to 6 weeks after last use of PCP. PCP

psycho-sis may also resemble mania or other mood disorders. Robust response of

psychotic symptoms to treatment with neuroleptics would favor a diagnosis other

than simple PCP psychosis.

PCP psychosis is readily distinguishable from LSD

psy-chosis in normal as well as in individuals with schizophrenia by the lack

of typical LSD effects, such as synesthesia. In cases involving prominent

PCP-induced neurological, cardiovascular, or metabolic derangement,

encephalitis, head injury, postictal state and primary metabolic disorders must

be ruled out. Either intoxication with or withdrawal from sedative–hypnotics

may be associated with nystagmus. Neuroleptic malignan at syndrome should be

ruled out in the differential diagnosis of PCP-induced hyperthermia and muscle

rigidity.

Course and Natural History

As drug levels decline, the clinical picture

recedes in five to 21 days through periods of moderating neurological,

autonomic and metabolic impairments to a stage at which only psychiatric

impairments are apparent. Once the physical symptoms and signs have cleared the

period of simple PCP psychosis may last 1 day to 6 weeks, whether or not

neuroleptics are administered, during which the psychiatric symptoms and signs

abate gradually and progressively. Even after complete recovery flashbacks may

oc-cur if PCP sequestered in lipid stores is mobilized. Any underly-ing

psychiatric disorders can be detected and evaluated only after complete

resolution of the drug-induced psychosis.

Overall Goals of Treatment

The hierarchy of treatment goals begins with

detection and treatment of physical manifestations of PCP intoxication. Equally

important are measures to anticipate PCP-induced impulsive, violent behaviors

and provide appropriate protec-tion for the patient and others. The patient

must then be closely observed during the period of PCP-induced psychosis, which

may persist for weeks after resolution of physical symptoms and signs. Finally,

the possibly dramatic medical and psychiat-ric presentation and its resolution

must not divert the attention of the psychiatrist from full assessment and

treatment of the patient’s drug-seeking behavior.

Physician–Patient Relationship in Psychiatric Management

In contrast to psychotic states induced by drugs

such as LSD, in which “talking the patient down” (by actively distracting the

pa-tient from his LSD-induced sensory distortions and convincing the patient

that his or her distress stems from nothing more than the temporary effects of

a drug that soon will wear off) may be highly effective, no such effort should

be made in the case of PCP psychosis, particularly during the period of acute

intoxication, because of the risk of sensory overload that can lead to

dramati-cally increased agitation. The risk of sudden and unpredictable

impulsive, violent behavior can also be increased by sensory stimulation.

Pharmacotherapy and Somatic Treatments

There is no pharmacological competitive antagonist

for PCP. Oral or intramuscular benzodiazepines are recommended for agitation.

Neuroleptics usually have little or no effect on acute or chronic PCP-induced

psychosis or thought disorder. Because they lower the seizure threshold,

neuroleptics should be used with caution. Physical restraint may be lifesaving

if the patient’s behavior poses an imminent threat to his or her safety or that

of others; however, such restraint risks triggering or worsening

rhabodomyolysis.

Related Topics