Chapter: Information Architecture on the World Wide Web : Designing Navigation Systems

Remote Navigation Elements

Remote Navigation Elements

Remote navigation elements or supplemental

navigation systems such as tables of contents, indexes, and site maps are

external to the basic hierarchy of a web site and provide an alternative bird's-eye

view of the site's content. Increasingly, we are seeing these remote navigation

elements displayed outside of the main browser window, in either a separate

target window or in a Java-based remote control panel. While remote navigation

elements can enhance access to web site content by providing complementary ways

of navigating, they should not be used as replacements or bandages for poor

organization and navigation systems. In many ways, remote navigation elements

are similar to software documentation or help systems. Documentation can be

very useful but will never save a bad product. Instead, remote navigation

elements should be used to complement a solid internal organization and

navigation system. You should provide them but never rely on them.

1. The Table of Contents

The table of contents and the index are the

state of the art in print navigation. Given that the design of these familiar

systems is the result of testing and refinement over the centuries, we should

not overlook their value for web sites.

In a book or magazine, the table of contents

presents the top few levels of the information hierarchy. It shows the

organization structure for the printed work and supports random as well as

linear access to the content through the use of chapter and page numbers.

Similarly, the table of contents for a web site presents the top few levels of

the hierarchy. It provides a broad view of the content in the site and

facilitates random access to segmented portions of that content. A web-based

table of contents can employ hypertext links to provide the user with direct

access to pages of the site.

You should consider using a table of contents

for web sites that lend themselves to hierarchical organization. If the

architecture is not strongly hierarchical, it makes no sense to present the

parent-child relationships implicit in a structured table of contents. You

should also consider the web site's size when deciding whether to employ a

table of contents. For a small site with only two or three hierarchical levels,

a table of contents may be unnecessary.

The design of a table of contents

significantly affects its usability. When working with a graphic designer, make

sure he or she understands the following rules of thumb:

1. Reinforce the information hierarchy so the

user becomes increasingly familiar with how the content is organized.

2. Facilitate fast, direct access to the contents

of the site for those users who know what they want.

3. Avoid overwhelming the user with too much

information. The goal is to help, not scare, the user.

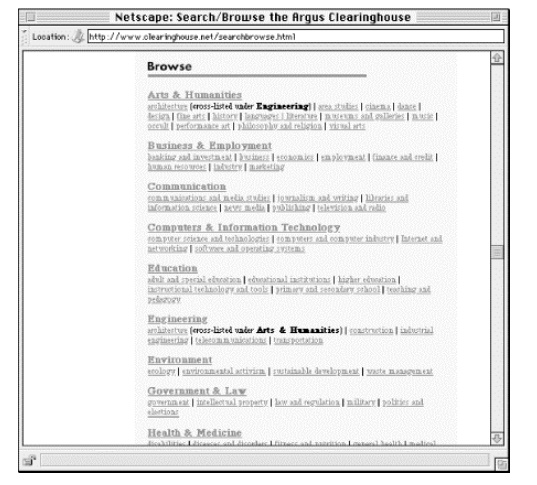

The Search/Browse

area of the Argus Clearinghouse, shown in Figure 4.14,

provides an example of a table of contents.

Figure 4.14. This table of contents allows users to select a

category (e.g., Arts & Humanities) or jump directly to a subcategory (e.g.,

architecture). Because of the clean page layout, users can quickly scan the

major and minor categories for the topic they're interested in.

Graphics can be used in the design and layout

of a table of contents, providing the designer with a finer degree of control

over the presentation. Colors, font styles, and a variety of graphic elements

can be applied to create a well-organized and aesthetically pleasing table of

contents. However, keep in mind that a graphic table of contents will cost more

to design and maintain and may slow down the page loading speed for the user.

When designing a navigation tool such as a table of contents, form is less

important than function.

2. The Index

For web sites that aren't conducive to strong

hierarchical organization, a manually created index can be a good alternative

to the more structured table of contents. Similar to an index found in print

materials, a web-based index presents keywords or phrases alphabetically, without

representing the hierarchy. Unlike a table of contents, indexes generally are

flat and present only one or two levels of depth. Therefore, indexes work very

well for users who already know the name of the item they are looking for. A

quick scan of the alphabetical listing will get them where they want to go.

A major challenge in indexing a web site

involves the level of granularity of indexing. Do you index web pages? Do you

index individual paragraphs or concepts that are presented on web pages? Or do you

index collections of web pages? In many cases, the answer may be all of the above. Perhaps a more

valuable question is: What terms are

users going to look for? Its answers should guide the index design. To

answer this question, you need to know your audience and understand their

needs. Before launch of the site, you can learn more about the terms that users

will look for through focus group sessions and individual user interviews.

After launch, you can employ a query tracking tool that captures and presents

all search terms entered by users. Analysis of these actual user search terms

should determine refinement of the index. (To learn more about query tracking

tools, see Chapter 9.)

In selecting items for the index, keep in mind

that an index should point only to destination pages, not navigation pages.

Navigation pages help users find (destination) pages through the use of menus

that begin on the main page and descend through the hierarchy. They are often

heavy on links and light on text. In contrast, destination pages contain the

content that users are trying to find. The purpose of the index is to enable

users to bypass the navigation pages and jump directly to these content-bearing

destination pages.

A useful trick in designing an index involves

term rotation, also known as permutation. A permuted index rotates the words in

a phrase so that users can find the phrase in two places in the alphabetical

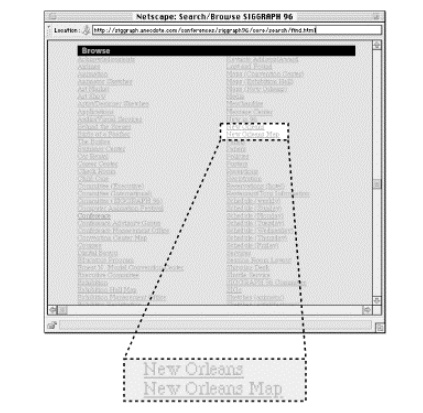

sequence. For example, in the SIGGRAPH 96 index shown in Figure 4.15, users will find listings for both New Orleans Maps and Maps (New Orleans). This supports the

varied ways people look for information. Term rotation should be applied

selectively. You need to balance the probability of users seeking a particular

term with the annoyance of cluttering the index with too many permutations. For

example, it would probably not make sense to present Sunday (Schedule) as well

as Schedule (Sunday). If you have the time and budget to conduct focus groups

or user testing, that's great. If not, you'll have to fall back on your common

sense.

Figure 4.15. The SIGGRAPH 96 index allows for multiple levels of

granularity. Selecting "New Orleans" will take you to a page that

introduces this adventurous city and includes a number of links. One of those

links takes you to a New Orleans map. Since this map is judged to be an

important content item, it is also presented in the index.

3. The Site Map

While the term site map is used indiscriminately in general practice, we define it

narrowly as a graphical representation of the architecture of a web site. This

definition excludes tables of contents and indexes that use graphic elements to

enhance the aesthetic appeal of tools that are primarily textual. A real site

map presents the information architecture in a way that goes beyond textual

representation.

Unlike tables of contents and indexes, maps

have not traditionally been used to facilitate navigation through bodies of

text. Maps are typically used for navigating physical rather than intellectual

space. This is significant for a few reasons. First, users are not familiar

with the use of site maps. Second, designers are not familiar with the design

of site maps. Third, most bodies of text (including most web sites) do not lend

themselves to graphical representations. As we discussed in Chapter 3, many web sites incorporate multiple

organization schemes and structures. Presenting this web of hypertextual

relationships visually is difficult. These reasons help explain why we see few

good examples on the Web of site maps that can improve navigation systems.

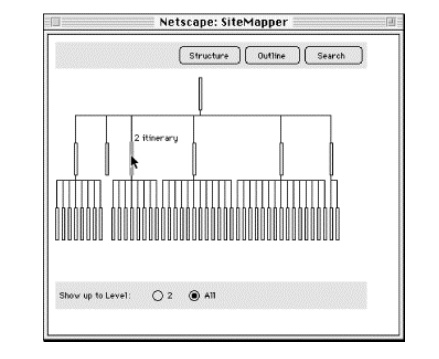

Figure 4.16 shows a site map from http://www.sgml.net. To learn more about automatically generated site maps, see http://www.webreview.com/97/05/16/arch/index.html.

Figure 4.16. In this example of an automatically generated site

map, gold bars represent pages within a web site. Users must roll their cursor

over a gold bar to see the title of the page. Do you think this approach is

more useful than a text-based table of contents?

If you decide to try a site map, consider

physical versus symbolic representation. Maps of the physical world do not

present the exact geography of an area. Accuracy and scale are often sacrificed

for representative contextual clues that help us find our way through the maze

of highways and byways to our destination. Often, the higher the level of

abstraction, the more intuitive the map. This rule of thumb holds true for all

of the remote navigation elements of web sites. When consulting a table of

contents or index or site map, a user doesn't need to see every single link on

every single page. They need to see the important links, presented in a clear

and meaningful way.

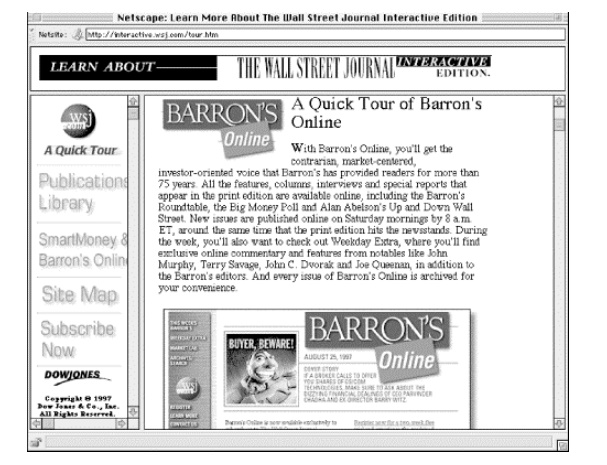

4. The Guided Tour

A guided tour serves as a nice tool for

introducing new users to the major content areas of a web site. It can be

particularly important for restricted access web sites (such as online

magazines that charge subscription fees) because you need to show potential

customers what they will get for their money.

A guided tour should feature linear navigation

(new users want to be guided, not thrown in), but a hypertextual navigation bar

may be used to provide additional flexibility. The tour should combine

screenshots of major pages with narrative text that explains what can be found in

each area of the web site. See Figure 4.17 for

an example.

Figure 4.17. In this example, the navigation options on each

screen allow users to move through the guided tour in a non-linear manner.

Remember that a guided tour is intended as an

introduction for new users and as a marketing opportunity for the web site.

Many people may never use it, and few people will use it more than once. For

that reason, you might consider linking to the tour from the gateway page7

rather than the main page. Also, you should balance the inevitable big ideas

about how to create an exciting, dynamic, interactive guided tour with the fact

that it will not play a central role in the day to day use of the web site.

Related Topics