Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Perioperative & Critical Care Medicine: Safety, Quality, & Performance Improvement

Quality of Care Performance Improvement Issues

QUALITY

OF CARE PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT ISSUES

It has long been recognized that quality and

safety are closely related to consistencyand reduction in practice variation.

The quality and safety movement(s) in medicine have their ori-gins in the work

of Walter Shewhart and his associ-ate W. Edwards Deming, who popularized the

use of statistics and control charts in evaluating the reli-ability of a

process. In manufacturing (where these ideas were initially applied), reducing

an error rate reduces the frequency of defective products and increases the

customer’s satisfaction with the prod-uct and the manufacturer. In medicine,

reducing the error rate (for everything from accurate timing and delivery of

prophylactic antibiotics to ensuring “cor-rect side and site” surgery and

regional anesthetic blocks) increases quality and reduces preventable injuries

to patients, while also eliminating the addi-tional costs resulting from those

errors.

Strategies to Reduce Performance Errors

Both in manufacturing and in medicine, there

is a natural tendency to assume that errorscan be prevented by better

education, better perfor-mance, or better management of individual workers. In other words, there is a tendency to look at

errors as individual failures made by individual workers, rather than as

failures of a system or a process. Using the latter point of view (as advocated

by Deming), to reduce errors one changes the system or process to reduce

unwanted variation so that random errors will be less likely. An outstanding

example of this is the universal protocol followed by health care insti-tutions

prior to invasive procedures. Adherence to this protocol ensures that the

correct procedure is performed on the correct part of the correct patient by

the correct physician, that the patient has given informed consent, that all

needed equipment and images are available, and that (if needed) the correct

prophylactic antibiotic was given at the correct time.

A related example of a simple approach to

improve safety and quality of a procedure is the use of a standardized

checklist, as described in the pop-ular press by Dr. Atul Gawande. The

importance of checklist use is addressed elsewhere in this text, for example in

the context of developing a culture of safety in the operating room. Such

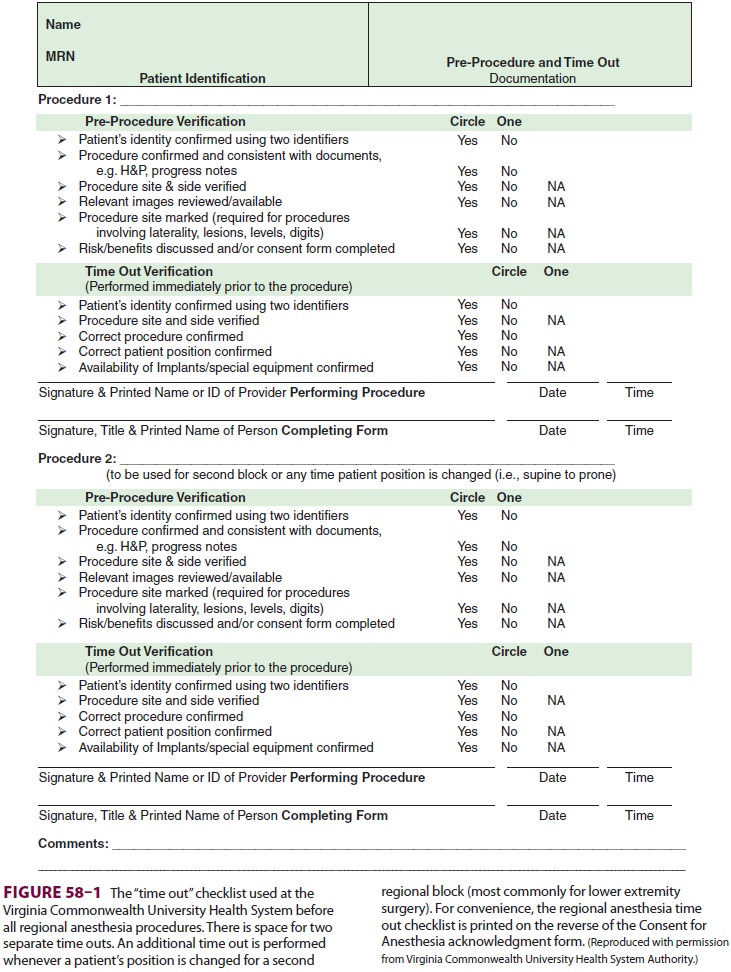

check-lists provide the “script” for the preprocedure uni-versal protocol (Figure

58–1). Studies have shown that the incidence of

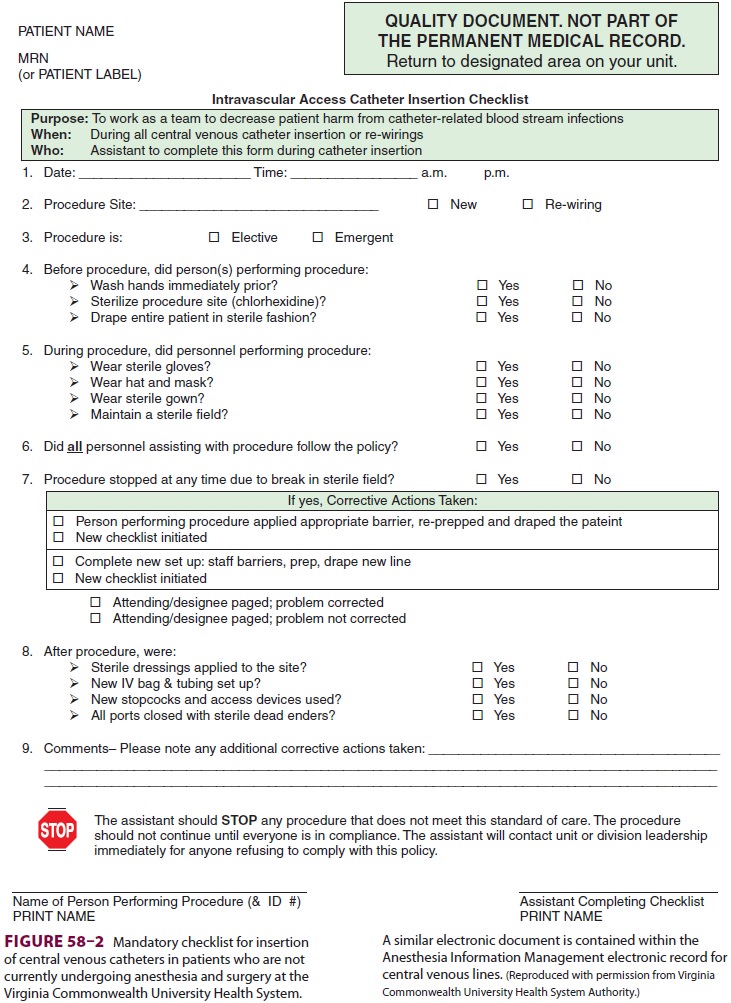

catheter-related bloodstream infections can be reduced when central venous

catheters are inserted after adequate cleansing and disinfection of the

operator’s hands by an operator wearing a surgical hat and mask, sterile gown,

and gloves; using chorhexidine (rather than povidone iodide) skin preparation

of the insertion site; and with sterile drapes of adequate size to maintain a

sterile field. Studies have also shown that use of all elements in this central

line “bundle” is much more likely when a checklist is required prior to every

central line insertion; a sample checklist is shown in Figure

58–2.

Benefits of Standardized Checklists

Checklists emphasize two important principles

about improving quality and safety in the surgical environment. First, using a

checklist requires that a physician communicate

with other members of the team. Good communication among team members improves

quality and prevents errors. It is easy to find examples of good communication

strategies. By clearly and forcefully announcing that protamine infusion has

been started (after extracorporeal perfusion has been discontinued during a

cardiac operation), the anesthesiologist helps prevent the surgeon and

perfusionist from making a critical error, such as resuming extracorporeal

perfusion without administering additional heparin. By accu-rately describing

the intended surgical procedure (at the time the patient is “posted” on the

surgical schedule), the surgeon helps prevent the operating room nurses from

making the critical error of not having the necessary instrumentation for the

pro-cedure, and helps prevent the anesthesiologist from performing the wrong

regional anesthetic proce-dure. We have selected these examples of good

com-munication because we are aware of adverse patient outcomes that resulted

from failure to transfer these specific points of information.

Second, using a checklist underscores the importance of ensuring that

every member of the surgical team has a stake in patient safety and good

surgical outcomes. The team member who records the checklist “results” is

usually not a physician but has the implicit authority to enforce adher-ence to

the checklist. On poorly functioning teams in which there is excessive

deference to authority figures, team members may feel that their opin-ions are

not wanted or valued, or may be afraid to bring up safety concerns for fear of

retaliation. On well-functioning teams, there is a “flattening” of the

hierarchy such that every team member has the authority and every team member

feels an obli-gation to halt the proceedings to prevent potential patient harm.

Quality Assurance Measures

In surgery there are well-recognized indicators of quality, such as having a very low incidence of surgical site infections and of perioperative mor-tality. However, at present there is no consensus as to the important measurements that can be used to assess quality of anesthesia care. Never-theless, surrogate anesthesia indicators have been monitored by a variety of well-meaning agencies. Examples include selection and timing of preop-erative antibiotics and temperature of patients in the postanesthesia care unit after colorectal sur-gery. Mindful of the importance of having accu-rate and relevant outcome measures, the ASA established the Anesthesia Quality Institute in 2009 and charged it with developing and collect-ing valid quality indicators for anesthetic care that can be used for quality improvement programs. Aggregation of the large amounts of data required for statistical validity is dependent on widespread adoption of electronic medical records (EMR) and anesthesia information management systems (AIMS). Currently these systems are present in a minority of hos-pitals in the United States. It is our hope that as their use becomes more widespread, the data and indicators that are collected and aggregated will provide greater insight into how quality of anes-thesia care may influence clinical outcomes that are important to patients.

Related Topics