Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Childhood Disorders: Feeding and Other Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood

Post Traumatic Feeding Disorder

Post Traumatic Feeding Disorder

Diagnostic Criteria

1. Food

refusal follows a traumatic event or repeated traumatic insults to the

oropharynx or gastrointestinal tract (e.g., chok-ing, severe vomiting, reflux,

insertion of nasogastric or en-dotracheal tubes, suctioning) that trigger

intense distress in the infant.

·

B. Consistent refusal to eat manifests in one of

the following ways:

·

Refuses to drink from the bottle, but may accept

food of-fered by spoon (although consistently refuses to drink from the bottle

when awake, may drink from the bottle when sleepy or asleep).

·

Refuses solid food, but may accept the bottle.

·

Refuses all oral feedings.

2.

Reminders of the traumatic event(s) cause distress

as mani-fested by one or more of the following:

·

Shows anticipatory distress when positioned for

feeding.

·

Shows intense resistance when approached with

bottle or food.

·

Shows intense resistance to swallow food placed in

the in-fant’s mouth.

3.

The food refusal poses an acute or long-term threat

to the child’s nutrition.

Epidemiology

Although no studies on the prevalence of this

disorder are avail-able, it appears that the occurrence of this feeding

disorder has been increasing because of the growing number of infants with

complex medical problems who survive.

Etiology

Although it is difficult to say what the inner

experience of a young infant might be, the affective and behavioral expressions

of in-fants provide a window to their inner life. In a study of infants

diagnosed with post traumatic feeding disorder, also including a control group

of healthy eaters and a group of anorectic infants matched by age, sex, race

and socioeconomic background, con-flict in mother–infant interactions during

feeding was present in both feeding-disordered groups. However, only those

subjects with a post traumatic feeding disorder demonstrated intense pre-oral

and intraoral feeding resistance. They appeared distressed, cried and pushed

the food away in anticipation of being fed, and kept solid food in their cheeks

or spat it out if the mothers were able to place any food in their mouths. The

mothers usually re-ported that these defensive behaviors started abruptly after

the infant experienced severe vomiting, gagging, or choking or un-derwent

invasive manipulation of the oropharynx (e.g., insertion of feeding and

endotracheal tubes or vigorous suctioning).

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

This feeding disorder is characterized by the

infant’s consistent refusal either to drink from the bottle or to eat any solid

foods, and in most severe cases, by the infant’s refusal to eat at all.

De-pending on the mode of feeding that the infants appear to associ-ate with

the traumatic event(s), some refuse to eat solids, but will continue to drink

from the bottle, whereas others may refuse to drink from the bottle, but are

willing to eat solids. Some infants may put baby food in their mouths, but then

spit out any food that has any little lumps in it. Most infants get stuck in

these food patterns and may lose weight or lack certain nutrients because of

their limited diet.

Reminders of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., the

bottle, the bib, or the high chair) may cause intense distress for some

infants, whereby they become fearful when they are positioned for feed-ings

and/or presented with feeding utensils and food. They resist being fed by

crying, arching and refusing to open their mouths. If food is placed in their

mouths, they intensely resist swallowing. They may gag or vomit, let the food

drop out, actively spit the food out, or store the food in their cheeks and spit

it out later. The fear of eating seems to override any awareness of hunger.

There-fore, infants who refuse all foods, including liquids and solids, require

acute intervention due to dehydration and starvation.

In addition to a thorough history about the onset

of the infant’s food refusal and the medical and developmental history, the

observation of the infant and mother during feeding is critical for

understanding this feeding disorder and differentiating it from infantile

anorexia and from sensory food aversions. It is helpful to ask the mother to

bring a variety of foods, including those that the infant refuses and those

that he or she accepts. Infants with a post traumatic feeding disorder

characteristically appear en-gaged and comfortable with their mothers as long

as the feared food is out of sight. Some infants begin to show distress when

they are placed in the high chair and they struggle to get away. In less severe

cases, the infant might allow the food to go into the mouth but then spit it out

and show distress only when urged to swallow. This anticipatory fear of food

differentiates infants with a post traumatic feeding disorder from anorectic

infants, whose food refusal appears random and related to issues of control in

the relationship with the mothers. Toddlers with sensory aversions to certain

types of food might also show distress when urged to eat these foods. However,

their mothers do not remember a traumatic event that seemed to trigger the food

refusal behaviors.

Course and Natural History

Most infants seem to get locked into their food

refusal patterns. The more anxiously the parents react to the infant’s food

refusal, the more anxious the infants appear to become, with the parent and the

infant feeding off each other’s anxiety. Individual case studies indicate that

some of these infants depend for years on gastrostomy feedings to survive.

Others may live on milk and puréed food until school age, when the social

embarrassment of their eating behavior urges the parents to seek help.

Treatment

Because of the complexity of many of these cases, a

multidisci-plinary team (consisting of a pediatrician or gastroenterologist, a

psychiatrist or psychologist, a social worker, an occupational therapist or

hearing and speech specialist, a nutritionist and a specially trained nurse to

serve as team coordinators) is best equipped to meet all the needs of these

infants and their parents.

Before any psychiatric treatment can be

successfully initi-ated, the medical and nutritional needs of the infant need

to be addressed. In severe cases of total food refusal, it is important to act

quickly to maintain the infant’s hydration. The medical and psychiatric team

members must work together to assess whether temporary nasogastric tube

feedings are indicated or whether plans for a gastrostomy should be made.

Unfortunately, the re-peated insertion of nasogastric feeding tubes can

intensify a post traumatic feeding disorder, and an infant in a labile medical

con-dition can take months if not years to recover.

The psychiatric treatment of this feeding disorder

involves a desensitization of the infant to overcome the anticipatory anxi-ety

about eating and return to internal regulation of eating in re-sponse to hunger

and satiety. It is most important to help the par-ents understand the dynamics

of a post traumatic feeding disorder so that they can recognize the infant’s

anticipatory anxiety and become active participants in the treatment. After

identification of triggers of anticipatory anxiety (e.g., the sight of the high

chair, the bottle, or certain types of food), a desensitization by gradual

exposure can be initiated or a more rapid desensitization through more

intensive behavioral techniques can be implemented.

With both techniques, it is important to have a

professional assess the infant’s oral motor coordination because many infants

who refuse to eat for extended periods fall behind in their oral motor

development due to lack of practice. The rapid introduc-tion of table food to a

child who has delayed oral motor skills may lead to choking, thereby creating a

setback to the desensitization process.

During the desensitization process, the infant has

to be re-inforced for swallowing the food. This behavioral manipulation of the

infant’s eating frequently leads to external regulation of eating in response

to the reinforcers. Once the infant has become comfortable with eating, it is

important to phase out these exter-nal reinforcers to allow the infant to

regain internal regulation of eating in response to hunger and fullness. This

can be a difficult transition because many infants gain control over their

parent’s emotions by eating or not eating. The techniques described under

infantile anorexia – the implementation of the feeding guidelines contained in

step 3 – can be helpful in making this transition.

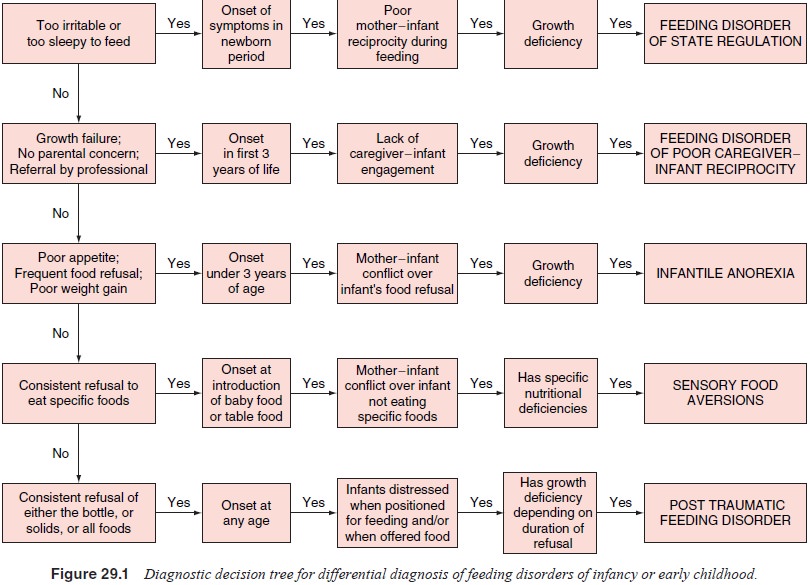

As summarized in Figure 29.1, each of these five

feeding disorders presents with specific symptom patterns and charac-teristic

mother–infant interactions, which help to diagnose and differentiate the

various feeding disorders. The correct diagno-sis is critical because a

treatment that is helpful for one feed-ing disorder may be ineffective or even

worsen another feeding disorder. For example, infants with infantile anorexia

become more aware of their hunger cues and feed better if fed only every4 hours

without being offered food or liquids in between meals. However, an infant with

post traumatic feeding disorder who is afraid of eating will not accept food

regardless of how long he or she has been kept without feeding. On the other

hand, behav-ioral techniques that help extinguish fear-based food refusal in a

post traumatic feeding disorder further distract an infant with infantile

anorexia and further interfere with the awareness of hunger.

Related Topics