Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Living representatives of primitive fishes

Polyodontidae - Class Actinopterygii, Subclass Chondrostei, Order Acipenseriformes: sturgeons and paddlefishes

Polyodontidae

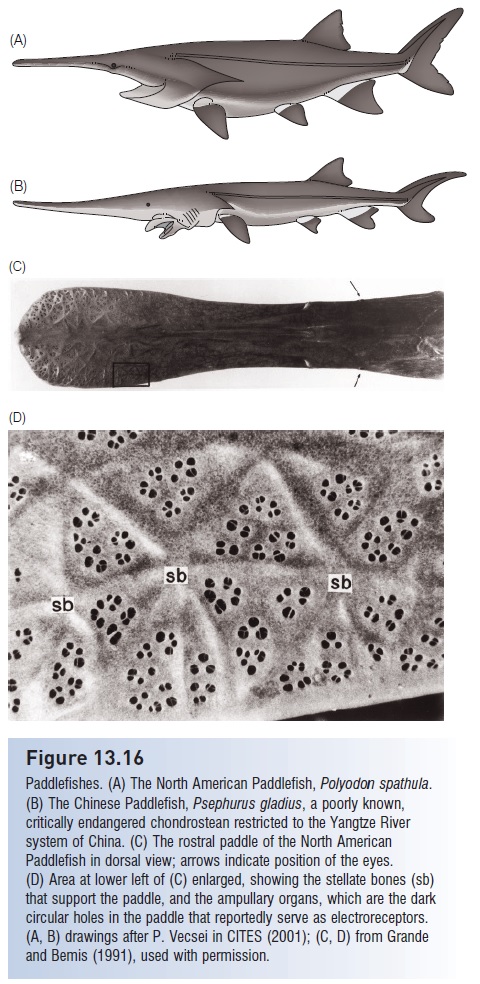

Paddlefishes also date back at least to the Early Cretaceous , but only two species remain, the Paddlefish of North America, Polyodon spathula, and the Chinese Paddlefish, Psephurus gladius (Fig. 13.16A, B). They have larvae similar to those of sturgeons and retain the heterocercal tail, unconstricted notochord, largely cartilaginous endoskeleton (with ossified head bones), spiracle, spiral valve intestine, and two small barbels. They differ from the acipenserids in most other respects. The bony scutes are missing and the body is essentially naked except for patches of minute scales. Paddlefishes are not benthic swimmers but instead move through the open waters of large, free-flowing rivers, feeding on zooplankton or fishes.

The North American Paddlefish, or spoonbill cat, prefers rivers with abundant zooplankton. Adult Paddlefish typically swim through the water both day and night with the nonprotrusible mouth open, straining zooplankton and aquatic insect larvae indiscriminately through the numerous, fine gill rakers. Food size is limited by gill raker spacing, as small zooplankters escape the mechanical sieve of the Paddlefish’s mouth (Rosen & Hales 1981). This picture of the Paddlefish as a passive filterer is confused by the occasional benthic and water column fishes, such as darters and shad, found in its stomach (Carlander 1969). Small juveniles, in which neither gill rakers nor the paddle are well developed, pick individual zooplankters out of the water column.

Figure 13.16

Paddlefishes. (A) The North American Paddlefish, Polyodon spathula. (B) The Chinese Paddlefish, Psephurus gladius, a poorly known, critically endangered chondrostean restricted to the Yangtze River system of China. (C) The rostral paddle of the North American Paddlefish in dorsal view; arrows indicate position of the eyes. (D) Area at lower left of (C) enlarged, showing the stellate bones (sb) that support the paddle, and the ampullary organs, which are the dark circular holes in the paddle that reportedly serve as electroreceptors. (A, B) drawings after P. Vecsei in CITES (2001); (C, D) from Grande and Bemis (1991), used with permission.

swim through the water both day and night with the nonprotrusible mouth open, straining zooplankton and aquatic insect larvae indiscriminately through the numerous, fine gill rakers. Food size is limited by gill raker spacing, as small zooplankters escape the mechanical sieve of the Paddlefish’s mouth (Rosen & Hales 1981). This picture of the Paddlefish as a passive filterer is confused by the occasional benthic and water column fishes, such as darters and shad, found in its stomach (Carlander 1969). Small juveniles, in which neither gill rakers nor the paddle are well developed, pick individual zooplankters out of the water column.

The function of the rostral paddle, which accounts for one-third of the body length in adults, remained something of a mystery until recently. It is now well established that the abundant ampullary receptors on the surface of the paddle and operculum serve to detect biologically generated electricity (Fig. 13.16C, D). Paddlefish, especially juveniles, use the ampullary receptors to detect weak electric fields created by individual plankton such as water fl eas (Daphnia) from distances of up to 9 cm, without using vision or other senses (Wilkens et al. 2002). The paddlefish rostrum is therefore equivalent to “an electrical antenna, enabling the fish to accurately detect and capture its planktonic food in turbid river environments where vision is severely limited” (Wilkens et al. 1997, p. 1723).

North American Paddlefish may live for 30 years and attain 2.2 m length and 83 kg mass, although fish of this size are now exceedingly rare. Diminishing populations are evidenced by changes in the species’ range. Although currently restricted to the Mississippi River drainage system, populations of Paddlefish historically occurred in the Laurentian Great Lakes and have been extirpated from at least four states (Gengerke 1986). Causes of population decline are similar to those affecting sturgeon. Paddlefish are long-lived but do not mature until they are 7–9 (males) or 10–12 (females) years old, and then spawn only at 2–5- year intervals. Loss of spawning habitat, which is fastfl owing, clean, gravel bottoms, is a major problem. Appropriate spawning areas are degraded by damming, which decreases water flow and leads to siltation. Paddlefish are sought commercially and recreationally for their flesh and eggs; overfishing has been frequently implicated in population declines (Russell 1986). Manmade reservoirs are productive feeding habitats for adults but do not provide appropriate spawning areas. Although not federally protected in the USA, all US states along the Missouri River have prohibited commercial fishing for it (Graham 1997b). The species has been listed in Appendix II of CITES, thus providing a mechanism to curtail overfishing and illegal trade, especially of Paddlefish caviar (Jennings & Zigler 2000).

The exceedingly rare, critically endangered, and poorly known Chinese Paddlefish, Psephurus gladius (see Fig. 13.16B), is the more primitive of the two species and differs primarily in head and jaw morphology and body size. The paddle is narrow and more pointed, not broad and rounded. Psephurus also has fewer but thicker gill rakers that resemble those of sturgeons, a protrusible mouth, and grows larger (over 3 m and 500 kg, erroneously reported to 7 m). It inhabits the Yangtze River system of central China and feeds primarily on small, water column and benthic fishes (Nichols 1943; Nikolsky 1961; Liu & Zeng 1988). Historically it also occurred in the Yellow River. Relatively little is known about its biology, including spawning habits, locales, or habitat (Liu & Zeng 1988; Grande & Bemis 1991;Birstein & Bemis 1995; Wei et al. 1997).

Psephurus is highly prized for its caviar but is now considered the most endangered fish in China because of overfishing, habitat destruction, and dam construction that blocks adults from reaching spawning grounds. It is probably anadromous, adults moving upriver to spawn and juveniles moving down to the East China Sea to grow. Gezhouba Dam on the Yangtze, completed in 1981, essentially cut the Paddlefish’s habitat in half and blocked spawning migrations. The species has had full protection in China since 1983 but no recruitment to the population is thought to be occurring, and fewer than 10 adult Paddlefish have been caught annually below the dam since 1988 (Wei et al. 1997). The massive Three Gorges Dam, scheduled for completion in 2009, will likely drive the species into extinction (Fu et al. 2003). Artifi cial propagation has been attempted but has failed because the fish cannot be kept in captivity.

The fossil record for polyodontids is limited to four known species and some fragments, the most primitive from the Lower Cretaceous of China and the others from the Upper Cretaceous, Paleocene, and Eocene of North America (Grande & Bemis 1991; Grande et al. 2002). The jaws and gill arches of the oldest species, Protopsephurus liui, resemble those of Psephurus, indicating that piscivory is the ancestral condition and that planktivory as observed in Polyodon is a derived trait (Grande et al. 2002).

Related Topics