Chapter: English Painting essay writing topics, sample examples for school, college students and Competitions

Painting : Variations on Goya

Variations on Goya

There

are anthologies of almost everything - from the best to the worst, from the

historically significant to the eccentric, from the childish to the sublime.

But there is one anthology, potentially the most interesting of them all,

which, to the best of my knowledge, has never yet been compiled; I mean, the

Anthology of Later Works.

To

qualify for inclusion in such an anthology, the artist would have to pass

several tests. First of all, he must have avoided a premature extinction and

lived on into artistic and chronological maturity. Thus the last poems of

Shelley, the last compositions of Schubert and even of Mozart would find no

place in our collection. Consummate artists as they were, these men were still

psychologically youthful when they died. For their full development they needed

more time than their earthly destiny allowed them. Of a different order are those

strange beings whose chronological age is out of all proportion to their

maturity, not only as artists, but as human spirits. Thus, some of the letters

written by Keats in his early twenties and many of the paintings which Seurat

executed before his death at thirty-two might certainly qualify as Later Works.

But, as a general rule, a certain minimum of time is needed for the ripening of

such fruits. For the most part, our hypothetical anthologist will make his

selections from the art of elderly and middle-aged men and women.

But

by no means all middle-aged and elderly artists are capable of producing

significant Later Works. For the last half century of a long life, Wordsworth

preserved an almost unbroken record of dullness. And in this respect he does not

stand alone. There are many, many others whose Later Works are their worst. All

these must be excluded from our anthology, and I would pass a similar judgment

on that other large class of Later Works which, though up to the standard of

the earlier, are not significantly different from them. Haydn lived to a ripe

old age and his right hand never forgot its cunning; but it also failed to

learn a new cunning. Peter Pan-like, he continued, as an old man, to write the

same sort of thing he had written twenty, thirty and forty years before. Where

there is nothing to distinguish the creations of a man's maturity from those of

his youth it is superfluous to include any of them in a selection of

characteristically Later Works.

This

leaves us, then, with the Later Works of those artists who have lived without

ever ceasing to learn of life. The field is relatively narrow; but within it,

what astonishing and sometimes what disquieting treasures! One thinks of the

ineffable serenity of the slow movement of Beethoven's A-Minor Quartet, the

peace passing all understanding of the orchestral prelude to the Benedictus of

his Missa Solemnis. But this is not the old man's only mood; when he

turns from the contemplation of eternal reality to a consideration of the human

world, we are treated to the positively terrifying merriment of the last

movement of his B-Flat-Major Quartet - merriment quite inhuman, peals of

violent and yet somehow abstract laughter echoing down from somewhere beyond

the limits of the world. Of the same nature, but if possible even more

disquieting, is the mirth which reverberates through the last act of Verdi's Falstaff,

culminating in that extraordinary final chorus in which the aged genius

makes his maturest comment on the world - not with bitterness or sarcasm or

satire, but in a huge, contrapuntal paroxysm of detached and already posthumous

laughter.

Turning

to the other arts, we find something of the same non-human, posthumous quality

in the Later Works of Yeats and, coupled with a prodigious majesty, in those of

Piero della Francesca. And then, of course there is The Tempest - a work

charged with something of the unearthly serenity of Beethoven's Benedictus but

concluding in the most disappointing anti-climax, with Prospero giving up his

magic for the sake (heaven help us!) of becoming once again a duke. And the

same sort of all too human anti-climax saddens us at the end of the second part

of Faust, with its implication that draining fens is Man's Final End,

and that the achievement of this end automatically qualifies the drainer for

the beatific vision.

And

what about the last El Grecos - for example, that unimaginable Immaculate

Conception at Toledo with its fantastic harmony of brilliant, ice-cold

colors, its ecstatic gesticulations in a heaven with a third dimension no

greater than that of a mine-shaft, its deliquescence of flesh and flowers and

drapery into a set of ectoplasmic abstractions? What about them, indeed? All we

know is that, beautiful and supremely enigmatic, they will certainly take their

place in our hypothetical anthology.

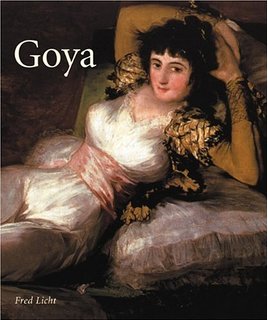

And

finally, among these and all other extraordinary Later Works, we should have to

number the paintings, drawings and etchings of Goya's final twenty-five or

thirty years.

The

difference between the young Goya and the old may be best studied and

appreciated by starting in the basement of the Prado, where his cartoons for

the tapestries are hung; climbing thence to the main floor, where there is a

room full of his portraits of royal imbeciles, grandees, enchanting duchesses, majas,

clothed and unclothed; walking thence to the smaller room containing the

two great paintings of the Second of May - Napoleon's Mamelukes cutting down

the crowd and, at night, when the revolt has been quelled, the firing squads at

work upon their victims by the light of lanterns; and finally mounting to the

top floor where hang the etchings and drawings, together with those unutterably

mysterious and disturbing "black paintings," with which the deaf and

aging Goya elected to adorn the dining room of his house, the Quinta del Sordo.

It is a progress from lighthearted eighteenth-century art, hardly at all

unconventional in subject matter or in handling, through fashionable brilliancy

and increasing virtuosity, to something quite timeless both in technique and

spirit - the most powerful of commentaries on human crime and madness, made in

terms of an artistic convention uniquely fitted to express precisely that

extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humor,

realism and fantasy.

"I

show you sorrow," said the Buddha, "and the ending of sorrow" -

the sorrow of the phenomenal world in which man, "like an angry ape, plays

such fantastic tricks before high heaven as make the angels weep," and the

ending of sorrow in the beatific vision, the unitive contemplation of

transcendental reality. Apart from the fact that he is a great and, one might

say, uniquely original artist, Goya is significant as being, in his Later

Works, the almost perfect type of the man who knows only sorrow and not the

ending of sorrow.

In

spite of his virulent anti-clericalism, Goya contrived to remain on

sufficiently good terms with the Church to receive periodical commissions to

paint religious pictures. Some of these, like the frescoes in the cupola of La

Florida, are frankly and avowedly secular. But others are serious essays in

religious painting. It is worth looking rather closely at what is probably the

best of these religious pieces - the fine Agony in the Garden. With

outstretched arms, Christ raises toward the comforting angel a face whose

expression is identical with that of the poor creatures whom we see, in a

number of unforgettably painful etchings and paintings, kneeling or standing in

an excruciating anticipation before the gun barrels of a French firing squad.

There is no trace here of that loving confidence which, even in the darkest

hours, fills the hearts of men and women who live continually in the presence

of God; not so much as a hint of what Francois de Sales calls "holy indifference"

to suffering and good fortune, of the fundamental equanimity, the peace passing

all understanding, which belongs to those whose attention is firmly fixed upon

a transcendental reality.

For

Goya the transcendental reality did not exist. There is no evidence in his

biography or his works that he ever had even the most distant personal

experience of it. The only reality he knew was that of the world around him;

and the longer he lived the more frightful did that world seem - the more

frightful, that is to say, in the eyes of his rational self; for his animal

high spirits went on bubbling up irrepressibly, whenever his body was free from

pain or sickness, to the very end. As a young man in good health, with money

and reputation, a fine position and as many women as he wanted, he had found

the world a very agreeable place - absurd, of course, and with enough of folly

and roguery to furnish subject matter for innumerable satirical drawings, but

eminently worth living in. Then all of a sudden came deafness, and, after the

joyful dawn of the Revolution, Napoleon and French imperialism and the

atrocities of war; and, when Napoleon's hordes were gone, the unspeakable

Ferdinand VII and clerical reaction and the spectacle of Spaniards fighting

among themselves; and all the time, like the drone of a bagpipe accompanying

the louder noises of what is officially called history, the enormous stupidity

of average men and women, the chronic squalor of their superstitions, the

bestiality of their occasional violences and orgies.

Realistically

or in fantastic allegories, with a technical mastery that only increased as he

grew older, Goya recorded it all - not only the agonies endured by his people

at the hands of the invaders, but also the follies and crimes committed by

these same people in their dealings with one another. The great canvases of the

Madrid massacres and executions, the incomparable etchings of War's

Disasters, fill us with an indignant compassion. But then we turn to the Disparates

and the Pinturas Negras. In these, with a sublimely impartial

savagery, Goya sets down exactly what he thinks of the martyrs of the Dos de

Mayo when they are not being martyred. Here, for example, are two men - two

Spaniards - sinking slowly toward death in an engulfing quicksand, but busily

engaged in knocking one another over the head with bludgeons. And here is a

rabble coming home from a pilgrimage - scores of low faces, distorted as though

by reflection in the back of a spoon, all open-mouthed and yelling. And all the

blank black eyes stare vacantly and idiotically in different directions.

These

creatures who haunt Goya's Later Works are inexpressibly horrible, with the

horror of mindlessness and animality and spiritual darkness. And above the

lower depths where they obscenely pullulate is a world of bad priests and

lustful friars, of fascinating women whose love is a "dream of lies and

inconstancy," of fatuous nobles and, at the top of the social pyramid, a

royal family of half-wits, sadists, Messalinas and perjurers. The moral of it

all is summed up in the central plate of the Caprichos, in which we see

Goya himself, his head on his arms, sprawled across his desk and fitfully

sleeping, while the air above is peopled with the bats and owls of necromancy

and just behind his chair lies an enormous witch's cat, malevolent as only

Goya's cats can be, staring at the sleeper with baleful eyes. On the side of

the desk are traced the words, "The dream of reason produces

monsters." It is a caption that admits of more than one interpretation.

When reason sleeps, the absurd and loathsome creatures of superstition wake and

are active, goading their victim to an ignoble frenzy. But this is not all.

Reason may also dream without sleeping, may intoxicate itself, as it did during

the French Revolution, with the daydreams of inevitable progress, of liberty,

equality and fraternity imposed by violence, of human self-sufficiency and the

ending of sorrow, not by the all too arduous method which alone offers any

prospect of success, but by political rearrangements and a better technology.

The Caprichos were published in the last year of the eighteenth century;

in 1808 Goya and all Spain were given the opportunity of discovering the

consequences of such daydreaming. Murat marched his troops into Madrid; the Desastres

de la Guerra were about to begin.

Goya

produced four main sets of etchings - the Caprichos, the Desastres de

la Guerra, the Tauromaquia and the Disparates or Proverbios.

All of them are Later Works. The Caprichos were not published until

he was fifty-three; the plates of the Desastres were etched between the

ages of sixty-five and seventy-five; the Tauromaquia series first saw

the light when he was sixty-nine (and at the age of almost eighty he learnt the

brand-new technique of lithography in order to be able to do justice to his

beloved bulls in yet another medium); the Disparates were finished when

he was seventy-three. For the non-Spaniard the plates of the Tauromaquia series

will probably seem the least interesting of Goya's etchings. They are brilliant

records of the exploits of the bull ring; but unfortunately, or fortunately,

most of us know very little about bullfighting. Consequently, we miss the finer

shades of the significance of these little masterpices of documentary art.

Moreover, being documentary, the etchings of the Tauromaquia do not lend

themselves to being executed with that splendid audacity, that dramatic breadth

of treatment, which delights us in the later paintings and the etchings of the

other three series. True, we find in this collection a few plates that are as

fine as anything Goya ever produced - for example, that wonderful etching of

the bull which has broken out of the arena and stands triumphant, a corpse

hanging limp across its horns, among the spectators' benches. But by and large

it is not to the Tauromaquia that we turn for the very best specimens of

Goya's work in black and white, or for the most characteristic expressions of

his mature personality. The nature of the subject matter makes it impossible

for him, in these plates to reveal himself fully either as a man or as an

artist.

Of

the three other sets of etchings two, the Caprichos and Disparates, are

fantastic and allegorical in subject matter, while the third, the Desastres,

though for the most part it represents real happenings under the Napoleonic

terror, represents them in a way which, being generalized and symbolical rather

than directly documentary, permits of, and indeed demands, a treatment no less

broad and dramatic than is given to the fantasies of the other collections.

War

always weakens and often completely shatters the crust of customary decency

which constitutes a civilization. It is a thin crust at the best of times, and

beneath it lies - what? Look through Goya's Desastres and find out. The

abyss of bestiality and diabolism and suffering seems almost bottomless. There

is practically nothing of which human beings are not capable when war or

revolution or anarchy gives them the necessary opportunity and excuse; and to

their pain death alone imposes a limit.

Goya's

record of disaster has a number of recurrent themes. There are those shadowy

archways, for example, more sinister than those even of Piranesi's Prisons, where

women are violated, captives squat in a hopeless stupor, corpses lie rotting,

emaciated children starve to death. Then there are the vague street corners at

which the famine-stricken hold out their hands; but the whiskered French

hussars and carabiniers look on without pity, and even the rich Spaniards pass

by indifferently, as though they were "of another lineage." Of still

more frequent occurrence in the series are the crests of those naked hillocks

on which lie the dead, like so much garbage. Or else, in dramatic silhouette

against the sky above those same hilltops, we see the hideous butchery of

Spanish men and women, and the no less hideous vengeance meted out by

infuriated Spaniards upon their tormentors. Often the hillock sprouts a single

tree, always low, sometimes maimed by gunfire. Upon its branches are impaled,

like the beetles and caterpillars in a butcher bird's larder, whole naked

torsos, sometimes decapitated, sometimes without arms, or else a pair of

amputated legs, or a severed head - warnings, set there by the conquerors, of

the fate awaiting those who dare oppose the Emperor. At other times the tree is

used as a gallows - a less efficient gallows, indeed, than that majestic oak

which, in Callot's Misères de la Guerre, is fruited with more than a score of swinging

corpses, but good enough for a couple of executions en passant, except,

of course, in the case recorded in one of Goya's most hair-raising plates, in

which the tree is too stumpy to permit of a man's hanging clear of the ground.

But the rope is fixed, none the less, and to tighten the noose around their

victim's neck, two French soldiers tug at the legs, while with his foot a third

man thrusts with all his strength against the shoulders.

And

so the record proceeds, horror after horror, unalleviated by any of the

splendors which other painters have been able to discover in war; for,

significantly, Goya never illustrates an engagement, never shows us impressive

masses of troops marching in column or deployed in the order of battle. His

concern is exclusively with war as it affects the civilian population, with armies

disintegrated into individual thieves and ravishers, tormentors and

executioners - and occasionally, when the guerilleros have won a

skirmish, into individual victims tortured in their turn and savagely done to

death by the avengers of their own earlier atrocities. All he shows us is war's

disasters and squalors, without any of the glory or even picturesqueness.

In

the two remaining series of etchings we pass from tragedy to satire and from

historical fact to allegory and pictorial metaphor and pure fantasy. Twenty

years separate the Caprichos from the Disparates, and the later

collection is at once more somber and more enigmatic than the earlier. Much of

the satire of the Caprichos is merely Goya's sharper version of what may

be called standard eighteenth-century humor. A plate such as Hasta la Muerte,

showing the old hag before her mirror, coquettishly trying on a new headdress,

is just Rowlandson-with-a-difference. But in certain other etchings a stranger

and more disquieting note is struck. Goya's handling of his material is such

that standard eighteenth-century humor often undergoes a sea-change into

something darker and queerer, something that goes below the anecdotal surface

of life into what lies beneath - the unplumbed depths of original sin and

original stupidity. And in the second half of the series the subject matter

reinforces the effect of the powerful and dramatically sinister treatment; for

here the theme of almost all the plates is basely supernatural. We are in a

world of demons, witches and familiars, half horrible, half comic, but wholly

disquieting inasmuch as it reveals the sort of thing that goes on in the

squalid catacombs of the human mind.

In

the Disparates the satire is on the whole less direct than in the Caprichos,

the allegories are more general and more mysterious. Consider, for example,

the technically astonishing plate, which shows a large family of three

generations perched like huddling birds along a huge dead branch that projects

into the utter vacancy of a dark sky. Obviously, much more is meant than meets

the eye. But what? The question is one upon which the commentators have spent a

great deal of ingenuity - spent it, one may suspect, in vain. For the satire,

it would seem, is not directed against this particular social evil or that

political mistake, but rather against unregenerate human nature as such. It is

a statement, in the form of an image, about life in general. Literature and the

scriptures of all the great religions abound in such brief metaphorical verdicts

on human destiny. Man turns the wheel of sorrow, burns in the fire of craving,

travels through a vale of tears, leads a life that is no better than a tale

told by an idiot signifying nothing.

Poor

man, what art? A tennis ball of error,

A

ship of glass tossed in a sea of terror:

Issuing

in blood and sorrow from the womb,

Crawling

in tears and mourning to the tomb.

How

slippery are thy paths, how sure thy fall!

How

art thou nothing, when thou art most of all!

And

so on. Good, bad and indifferent, the quotations could be multiplied almost

indefinitely. In the language of the plastic arts, Goya has added a score of

memorable contributions to the stock of humanity's gnomic wisdom.

The Disparates

of the dead branch is relatively easy to understand. So is the comment on

Fear contained in the plate which shows soldiers running in terror from a

gigantic cowled figure, spectral against a jet black sky. So is the etching of

the ecstatically smiling woman riding a stallion that turns its head and, seizing

her skirts between its teeth, tries to drag her from her seat. The allegorical

use of the horse, as a symbol of the senses and the passions, and of the

rational rider or charioteer who is at liberty to direct or be run away with,

is at least as old as Plato.

But

there are other plates in which the symbolism is less clear, the allegorical

significance far from obvious. That horse on a tightrope, for example, with a

woman dancing on its back; the men who fly with artificial wings against a sky

of inky menace; the priests and the elephant; the old man wandering among

phantoms: what is the meaning of these things? And perhaps the answer to that

question is that they have no meaning in any ordinary sense of the word; that

they refer to strictly private events taking place on the obscurer levels of

their creator's mind. For us who look at them, it may be that their real point

and significance consist precisely in the fact that they image forth so

vividly, and yet, of necessity, so darkly and incomprehensibly, some at least

of the unknown quantities that exist at the heart of every personality.

Goya

once drew a picture of an ancient man tottering along under the burden of

years, but with the accompanying caption, "I'm still learning." That

old man was himself. To the end of a long life, he went on learning. As a very

young man he paints like the feeble eclectics who were his masters. The first

signs of power and freshness and originality appear in the cartoons for the

tapestries, of which the earliest were executed when he was thirty. As a

portraitist, however, he achieves nothing of outstanding interest until he is

almost forty. But by that time he really knows what he's after, and during the

second forty years of his life he moves steadily forward toward the consummate

technical achievements, in oils, of the Pinturas Negras, and, in

etching, of the Desastres and the Disparates. Goya's is a

stylistic growth away from restraint and into freedom, away from timidity and

into expressive boldness.

From

the technical point of view the most striking fact about almost all Goya's

successful paintings and etchings is that they are composed in terms of one or

more clearly delimited masses standing out from the background - often indeed,

silhouetted against the sky. When he attempts what may be called an

"all-over" composition, the essay is rarely successful. For he lacks

almost completely the power which Rubens so conspicuously possessed - the power

of filling the entire canvas with figures or details of landscape, and upon that

plenum imposing a clear and yet exquisitely subtle three-dimensional

order. The lack of this power is already conspicuous in the tapestry cartoons,

of which the best are invariably those in which Goya does his composing in

terms of silhouetted masses and the worst those in which he attempts to

organize a collection of figures distributed all over the canvas. And compare,

from this point of view, the two paintings of the Dos de Mayo - the Mamelukes

cutting down the crowd in the Puerta del Sol, and the firing squads at work in

the suburbs, after dark. The first is an attempt to do what Rubens would have

done with an almost excessive facility - to impose a formally beautiful and

dramatically significant order upon a crowd of human and animal figures

covering the greater part of the canvas. The attempt is not successful, and in

spite of its power and the beauty of its component parts, the picture as a

whole is less satisfying as a composition, and for that reason less moving as a

story, than is the companion piece, in which Goya arranges his figures in a

series of sharply delimited balancing groups, dramatically contrasted with one

another and the background. In this picture the artist is speaking his native

language, and he is therefore able to express what he wants to say with the

maximum force and clarity. This is not the case with the picture of the

Mamelukes. Here, the formal language is not truly his own, and consequently his

eloquence lacks the moving power it possesses when he lets himself go in the

genuine Goyescan idiom.

Fortunately,

in the etchings, Goya is very seldom tempted to talk in anything else. Here he

composes almost exclusively in terms of bold separate masses, silhouetted in

luminous grays and whites against a darkness that ranges from stippled

pepper-and-salt to intense black, or in blacks and heavily shaded grays against

the whiteness of virgin paper. Sometimes there is only one mass, sometimes

several, balanced and contrasted. Hardly ever does he make the, for him, almost

fatal mistake of trying to organize his material in an all-over composition.

With

the Desastres and the Disparates his mastery of this, his

predestined method of composition, becomes, one might say, absolute. It is not,

of course, the only method of composition. Indeed, the nature of this

particular artistic idiom is such that there are probably certain things that

can never be expressed in it - things which Rembrandt, for example, was able to

say in his supremely beautiful and subtle illustrations to the Bible. But

within the field that he chose to cultivate - that the idiosyncrasies of his

temperament and the quality of his artistic sensibilities compelled him to

choose - Goya remains incomparable.

(From Themes and Variations; originally

published in Complete

Etchings of Goya.

Used by permission of Crown Publishers, Inc.)

Related Topics