Chapter: Paediatrics: Pharmacology and therapeutics

Paediatrics: Adverse drug reactions

One in 10 children in hospital and

one in 100 attending outpatients will experience an adverse drug reaction

(ADR). 71 in 8 will be severe. ADRs are responsible for almost 2% of children

admitted to hospital. ADRs in children can be as varied as in adults. Children,

because of growth and development, also suffer specific ADRs. Differences in

drug metabolism make certain ADRs a greater problem in children, e.g. valproate

hepato-toxicity, or less of a problem, e.g. paracetamol hepatotoxicity following

an overdose. The mechanisms of ADRs specifically affecting children are

illustrated with examples below.

Mechanisms of ADRs

Impaired drug metabolism

Chloramphenicol, when first used

in neonates, led to the development of the grey baby syndrome (vomiting,

cyanosis, cardiovascular collapse, and in some cases death). The newborn infant

metabolizes chloramphenicol more slowly than adults and so only requires a

lower dose of the antibi-otic. Reduction in the dosage prevents grey baby

syndrome.

Children, particularly neonates,

are more likely to have a reduced capac-ity to metabolize drugs than adults.

Therefore, lower doses are usually required.

Altered drug metabolism

Children may have reduced activity

of the major hepatic enzymes associ-ated with drug metabolism. To compensate

for this, they may use other enzyme pathways. This is thought to be one of the

factors contributing to the increased risk of hepatotoxicity in children under

the age of 3 years who receive sodium valproate. This risk is raised by the

concurrent use of other anticonvulsants which may cause enzyme induction of

certain metabolic pathways.

Sodium valproate should not be

used as a first-line anticonvulsant in children under the age of 3yrs.

Protein-displacing effect on bilirubin

The use of the sulphonamide

sulphisoxazole in ill neonates in the 1950s was associated with the development

of fatal kernicterus due to drug dis-placement of protein bound bilirubin into

the blood because of its higher binding affinity to albumin. Ceftriaxone also

is highly protein bound and will displace bilirubin in sick neonates.

The protein-displacing effect of

medicines should be considered in sick preterm neonates.

Percutaneous absorption

Percutaneous

toxicity can be a significant prob-lem in the neonatal period due to their

higher surface area to weight

ratio than that of both children

and adults. An example of this is the use of antiseptic agents such as

hexachlorophene that have been associated with neurotoxicity.

Drug interactions

Ceftriaxone

and calcium containing solutions when used

together in neonates may result in the precipitation of ceftriaxone— calcium

salt in the lungs. This drug interaction can result in fatalities and therefore

ceftriaxone should be avoided in neonates.

Ceftriaxone should be avoided in

neonates.

Unknown

There are several examples of

major ADRs that occur in children for which we do not understand the mechanism.

Salicylate given during the presence of a viral illness increases the risk of

the development of Reye’s syndrome in children of all ages. Since the use of

salicylates has been avoided in chil-dren the incidence of Reye’s syndrome has

dramatically reduced. Propofol has minimal toxicity when used to induce general

anaesthesia. Used as a sedative in critically ill children, however, it has

been associated with the death of over 10 children in the UK alone. The

propofol infusion syn-drome is thought to be related to the total dose of

propofol infused, i.e. high dose or prolonged duration is more likely to cause

problems.

Propofol should not be used as a

sedative in critically ill children

Suspect ADRs

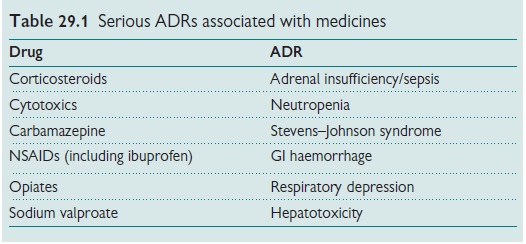

One should always

consider the possibility of an ADR being responsible for a child’s

symptoms. Table 29.1 lists some of the seri-ous ADRs associated with widely used

medicines.

Preventing ADRs

Recognizing which

patients are at greater risk of ADRs can help reduce the overall

incidence. Health professionals should follow guidelines.

Reporting ADRs

Suspected ADRs

should be reported to the regula-tory authorities. In the UK the yellow card

scheme is in operation.

Related Topics