Chapter: Information Architecture on the World Wide Web : Organizing Information

Organizing Web Sites and Intranets

Organizing Web Sites and Intranets

The organization of information in web sites

and intranets is a major factor in determining success, and yet many web

development teams lack the understanding necessary to do the job well. Our goal

in this chapter is to provide a foundation for tackling even the most

challenging information organization projects.

Organization systems are composed of organization schemes and organization structures . An

organization scheme defines the shared characteristics of content items and

influences the logical grouping of those items. An organization structure

defines the types of relationships between content items and groups.

Before diving in, it's important to understand

information organization in the context of web site development. Organization

is closely related to navigation, labeling, and indexing. The hierarchical

organization structures of web sites often play the part of primary navigation

system. The labels of categories play a significant role in defining the

contents of those categories. Manual indexing is ultimately a tool for

organizing content items into groups at a very detailed level. Despite these

closely knit relationships, it is both possible and useful to isolate the

design of organization systems, which will form the foundation for navigation

and labeling systems. By focusing solely on the logical grouping of

information, you avoid the distractions of implementation details and design a

better web site.

1. Organization Schemes

We navigate through organization schemes every

day. Phone books, supermarkets, and television programming guides all use

organization schemes to facilitate access. Some schemes are easy to use. We

rarely have difficulty finding a friend's phone number in the alphabetical

organization scheme of the white pages. Some schemes are intensely frustrating.

Trying to find marshmallows or popcorn in a large and unfamiliar supermarket

can drive us crazy. Are marshmallows in the snack aisle, the baking ingredients

section, both, or neither?

In fact, the organization schemes of the phone

book and the supermarket are fundamentally different. The alphabetical

organization scheme of the phone book's white pages is exact. The hybrid

topical/task-oriented organization scheme of the supermarket is ambiguous.

1.1 Exact organization schemes

Let's start with the easy ones. Exact

organization schemes divide information into well defined and mutually

exclusive sections. The alphabetical organization of the phone book's white

pages is a perfect example. If you know the last name of the person you are

looking for, navigating the scheme is easy. Porter

is in the P's which is after the O's but before the Q's. This is called "

known-item" searching. You know what you're looking for and it's obvious

where to find it. No ambiguity is involved. The problem with exact organization

schemes is that they require the user to know the specific name of the resource

they are looking for. The white pages don't work very well if you're looking

for a plumber.

Exact organization schemes are relatively easy

to design and maintain because there is little intellectual work involved in

assigning items to categories. They are also easy to use. The following

sections explore three frequently used exact organization schemes.

1.1.1 Alphabetical

An alphabetical organization scheme is the

primary organization scheme for encyclopedias and dictionaries. Almost all

nonfiction books, including this one, provide an alphabetical index. Phone

books, department store directories, bookstores, and libraries all make use of

our 26-letter alphabet for organizing their contents. Alphabetical organization

often serves as an umbrella for other organization schemes. We see information

organized alphabetically by last name, by product or service, by department,

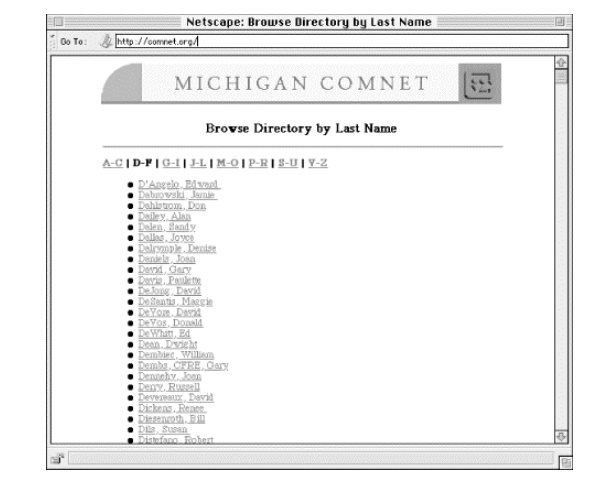

and by format. See Figure 3.1 for an example.

Figure 3.1. An alphabetical index supports both rapid

scanning for a known item and more casual browsing of a directory.

1.1.2 Chronological

Certain types of information lend themselves

to chronological organization. For example, an archive of press releases might

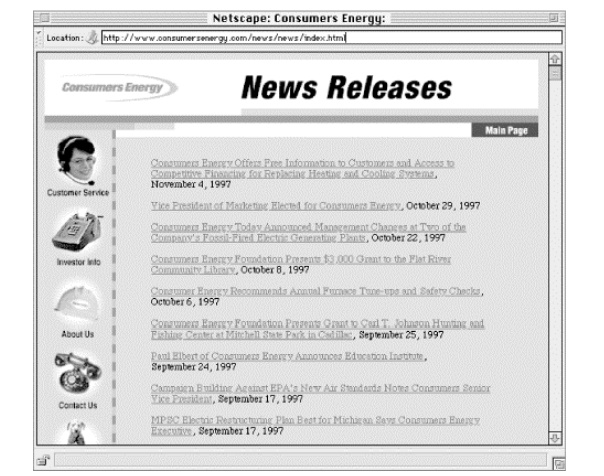

be organized by the date of release (see Figure 3.2).

History books, magazine archives, diaries, and television guides are organized

chronologically. As long as there is agreement on when a particular event

occurred, chronological schemes are easy to design and use.

Figure 3.2. Press release archives are obvious

candidates for chronological organization schemes. The date of announcement

provides important context for the release. However, keep in mind that users

may also want to browse the releases by title or search by keyword. A

complementary combination of organization schemes is often necessary.

1.1.3 Geographical

Place is often an important characteristic of

information. We travel from one place to another. We care about the news and

weather that affects us in our location. Political, social, and economic issues

are frequently location-dependent. With the exception of border disputes,

geographical organization schemes are fairly straightforward to design and use.

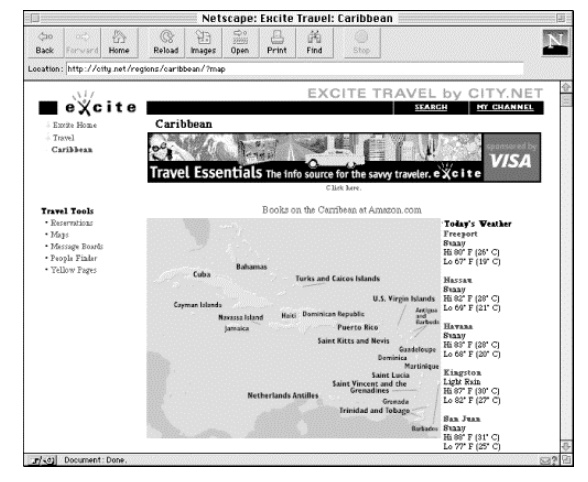

Figure 3.3 shows an example of a geographic

organization scheme.

Figure 3.3. In this example, the map presents a

graphical view of the geographic organization scheme. Users can select a

location from the map using their mouse.

1.2 Ambiguous organization schemes

Now for the tough ones. Ambiguous organization

schemes divide information into categories that defy exact definition. They are

mired in the ambiguity of language and organization, not to mention human

subjectivity. They are difficult to design and maintain. They can be difficult

to use. Remember the tomato? Do we put it under fruit, berry, or vegetable?

However, they are often more important and

useful than exact organization schemes. Consider the typical library catalog.

There are three primary organization schemes. You can search for books by

author, by title, or by subject. The author and title organization schemes are

exact and thereby easier to create, maintain, and use. However, extensive

research shows that library patrons use ambiguous subject-based schemes such as

the Dewey Decimal and Library of Congress Classification Systems much more

frequently.

There's a simple reason why people find

ambiguous organization schemes so useful: We

don't always know what we're looking

for. In some cases, you simply don't know the correct label. In others, you

may only have a vague information

need that you can't quite articulate. For these reasons, information seeking is

often iterative and interactive. What you find at the beginning of your search

may influence what you look for and find later in your search. This information

seeking process can involve a wonderful element of associative learning. Seek

and ye shall find, but if the system is well-designed, you also might learn

along the way. This is web surfing at its best.

Ambiguous organization supports this

serendipitous mode of information seeking by grouping items in intellectually

meaningful ways. In an alphabetical scheme, closely grouped items may have

nothing in common beyond the fact that their names begin with the same letter.

In an ambiguous organization scheme, someone other than the user has made an

intellectual decision to group items together. This grouping of related items

supports an associative learning process that may enable the user to make new

connections and reach better conclusions. While ambiguous organization schemes

require more work and introduce a messy element of subjectivity, they often

prove more valuable to the user than exact schemes.

The success of ambiguous organization schemes

depends on the initial design of a classification system and the ongoing

indexing of content items. The classification system serves as a structured

container for content items. It is composed of a hierarchy of categories and

subcategories with scope notes that define the types of content to be included

under each category. Once this classification system has been created, content

items must be assigned to categories accurately and consistently. This is a

painstaking process that only a librarian could love. Let's review a few of the

most common and valuable ambiguous organization schemes.

1.2.1 Topical

Organizing information by subject or topic is

one of the most challenging yet useful approaches. Phone book yellow pages are

organized topically. That's why they're the right place to look when you need a

plumber. Academic courses and departments, newspapers, and the chapters of most

nonfiction books are all organized along topical lines.

While few web sites should be organized solely

by topic, most should provide some sort of topical access to content. In

designing a topical organization scheme, it is important to define the breadth

of coverage. Some schemes, such as those found in an encyclopedia, cover the

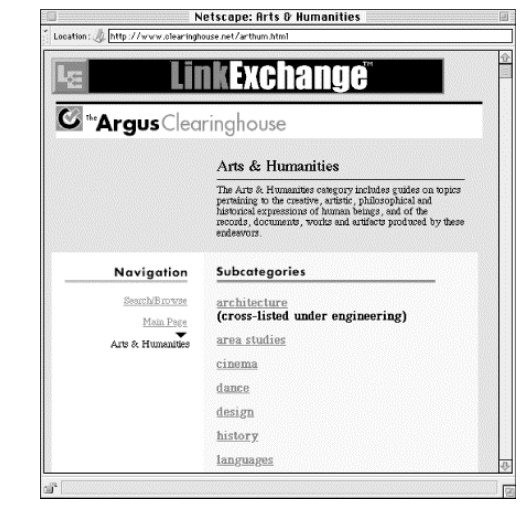

entire breadth of human knowledge (see Figure 3.4 for an example).

Others, such as those more commonly found in corporate web sites, are limited in breadth, covering only

those topics directly related to that company's products and services. In

designing a topical organization scheme, keep in mind that you are defining the

universe of content (both present and future) that users will expect to find within

that area of the web site.

Figure 3.4. Research-oriented web sites such as the

Argus Clearinghouse rely heavily on their topical organization scheme. In this

example, the scope note for the Arts and Humanities category is presented as

well as the list of subcategories. This helps the user to understand the

reasoning behind the inclusion or exclusion of specific subcategories.

1.2.2 Task-oriented

Task-oriented schemes organize content and

applications into a collection of processes, functions, or tasks. These schemes

are appropriate when it's possible to anticipate a limited number of

high-priority tasks that users will want to perform. Desktop software

applications such as word processors and spreadsheets provide familiar examples.

Collections of individual actions are organized under task-oriented menus such

as Edit,

Insert, and

Format.

On today's Web, task-oriented organization

schemes are less common, since most web sites are content rather than

application intensive. This should change as sites become increasingly

functional. Intranets and extranets lend themselves well to a task orientation,

since they tend to integrate powerful applications as well as content. Figure 3.5 shows an example of a task-oriented site.

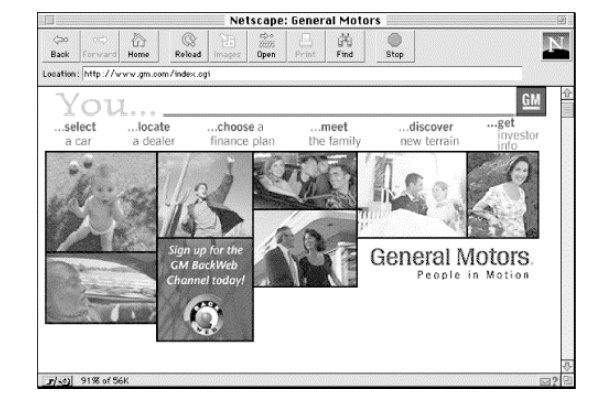

Figure 3.5. In this example, General Motors anticipates

some of the most important needs of users by presenting a task-based menu of

action items. This approach enables GM to quickly funnel a diverse user base

into specific action-oriented areas of the web site.

1.2.3 Audience-specific

In cases where there are two or more clearly

definable audiences for a web site or intranet, an audience-specific

organization scheme may make sense. This type of scheme works best when the

site is frequented by repeat visitors who can bookmark their particular section

of the site. Also, it works well if there is value in customizing the content

for each audience. Audience-oriented schemes break a site into smaller,

audience-specific mini-sites, thereby allowing for clutter-free pages that

present only the options of interest to that particular audience. See Figure 3.6 for an example.

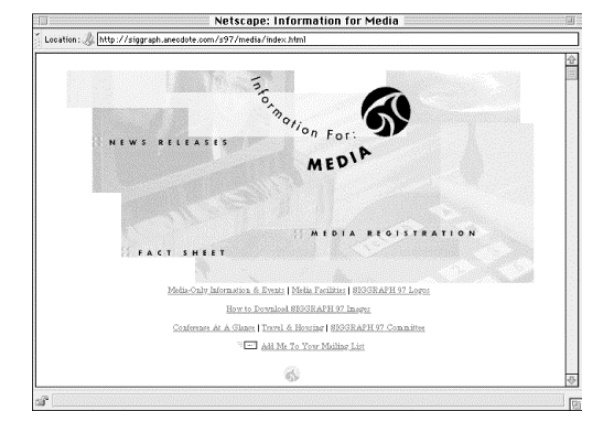

Figure 3.6. This area of the SIGGRAPH 97 conference web

site is designed to meet the unique needs of media professionals covering the

conference. Other SIGGRAPH audiences with special needs include contributors

and exhibitors.

Audience-specific schemes can be open or

closed. An open scheme will allow members of one audience to access the content

intended for other audiences. A closed scheme will prevent members from moving

between audience-specific sections. A closed scheme may be appropriate if

subscription fees or security issues are involved.

1.2.4 Metaphor-driven

Metaphors are commonly used to help users

understand the new by relating it to the familiar. You need not look further

than your desktop computer with its folders, files, and trash can or recycle bin for an example. Applied to

an interface in this way, metaphors can help users understand content and

function intuitively. In addition, the process of exploring possible

metaphor-driven organization schemes can generate new and exciting ideas about

the design, organization, and function of the web site (see "Metaphor

Exploration" in Chapter 8).

While metaphor exploration can be very useful

while brainstorming, you should use caution when considering a metaphor-driven

global organization scheme. First, metaphors, if they are to succeed, must be

familiar to users. Organizing the web site of a computer hardware vendor

according to the internal architecture of a computer will not help users who

don't understand the layout of a motherboard.

Second, metaphors can introduce unwanted

baggage or be limiting. For example, users might expect a virtual library to be

staffed by a librarian that will answer reference questions. Most virtual

libraries do not provide this service. Additionally, you may wish to provide

services in your virtual library that have no clear corollary in the real

world. Creating your own customized version of the library is one such example.

This will force you to break out of the metaphor, introducing inconsistency

into your organization scheme.

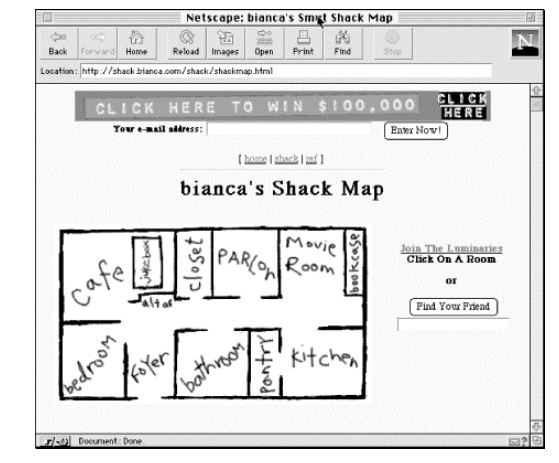

Figure 3.7 shows a more offbeat metaphor

example.

Figure 3.7. In this offbeat example, Bianca has

organized the contents of her web site according to the metaphor of a physical

shack with rooms. While this metaphor-driven approach is fun and conveys a

sense of place, it is not particularly intuitive. Can you guess what you'll

find in the pantry? Also, note that features such as Find Your Friend don't fit

neatly into the metaphor.

1.3 Hybrid schemes

The power of a pure organization scheme

derives from its ability to suggest a simple mental model for users to quickly

understand. Users easily recognize an audience-specific or topical

organization. However, when you start blending elements of multiple schemes,

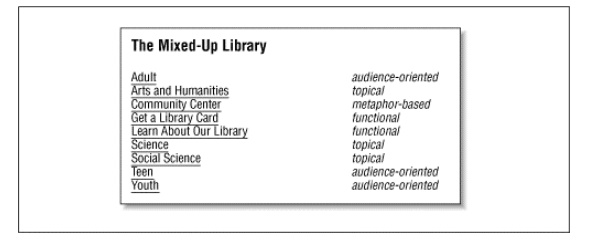

confusion is almost guaranteed. Consider the example of a hybrid scheme in Figure 3.8. This hybrid scheme includes elements of

audience-specific, topical, metaphor-based, and task-oriented organization

schemes. Because they are all mixed together, we can't form a mental model.

Instead, we need to skim through each menu item to find the option we're

looking for.

Figure 3.8. A hybrid organization scheme

Examples of hybrid schemes are common on the

Web. This happens because it is often difficult to agree upon any one scheme to

present on the main page, so people throw the elements of multiple schemes

together in a confusing mix. There is a better alternative. In cases where

multiple schemes must be presented on one page, you should communicate to

designers the importance of retaining the integrity of each scheme. As long as

the schemes are presented separately on the page, they will retain the powerful

ability to suggest a mental model for users (see Figure

3.9 for an example).

Figure 3.9. Notice that the audience-oriented scheme

(contributors, exhibitors, media) has been presented as a pure organization

scheme, separate from the others on this page. This approach allows you to

present multiple organization schemes on the same page without causing

confusion.

2. Organization Structures

Organization structure plays an intangible yet

very important role in the design of web sites. While we interact with

organization structures every day, we rarely think about them. Movies are

linear in their physical structure. We experience them frame by frame from

beginning to end. However, the plots themselves may be non-linear, employing

flashbacks and parallel subplots. Maps have a spatial structure. Items are

placed according to physical proximity, although the most useful maps cheat,

sacrificing accuracy for clarity.

The structure of information defines the

primary ways in which users can navigate. Major organization structures that

apply to web site and intranet architectures include the hierarchy, the

database-oriented model, and hypertext. Each organization structure possesses

unique strengths and weaknesses. In some cases, it makes sense to use one or

the other. In many cases, it makes sense to use all three in a complementary

manner.

2.1 The hierarchy: A top-down approach

The foundation of almost all good information

architectures is a well-designed hierarchy. In this hypertextual world of nets

and webs, such a statement may seem blasphemous, but it's true. The mutually

exclusive subdivisions and parent-child relationships of hierarchies are simple

and familiar. We have organized information into hierarchies since the

beginning of time. Family trees are hierarchical. Our division of life on earth

into kingdoms and classes and species is hierarchical. Organization charts are

usually hierarchical. We divide books into chapters into sections into paragraphs

into sentences into words into letters. Hierarchy is ubiquitous in our lives

and informs our understanding of the world in a profound and meaningful way.

Because of this pervasiveness of hierarchy, users can easily and quickly

understand web sites that use hierarchical organization models. They are able

to develop a mental model of the site's structure and their location within

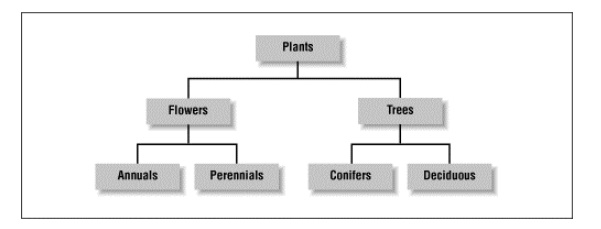

that structure. This provides context that helps users feel comfortable. See Figure 3.10 for an example of a simple hierarchical

model.

Figure 3.10. A simple hierarchical organization model.

Because hierarchies provide a simple and

familiar way to organize information, they are usually a good place to start

the information architecture process. The top-down approach allows you to

quickly get a handle on the scope of the web site without going through an

extensive content inventory process. You can begin identifying the major

content areas and exploring possible organization schemes that will provide

access to that content.

2.2 Designing hierarchies

When designing information hierarchies on the

Web, you should remember a few rules of thumb. First, you should be aware of,

but not bound by, the idea that hierarchical categories should be mutually

exclusive. Within a single organization scheme, you will need to balance the

tension between exclusivity and inclusivity. Ambiguous organization schemes in

particular make it challenging to divide content into mutually exclusive

categories. Do tomatoes belong in the fruit or vegetable or berry category? In

many cases, you might place the more ambiguous items into two or more

categories, so that users are sure to find them. However, if too many items are

cross-listed, the hierarchy loses its value. This tension between exclusivity

and inclusivity does not exist across different organization schemes. You would

expect a listing of products organized by format to include the same items as a

companion listing of products organized by topic. Topic and format are simply

two different ways of looking at the same

information.

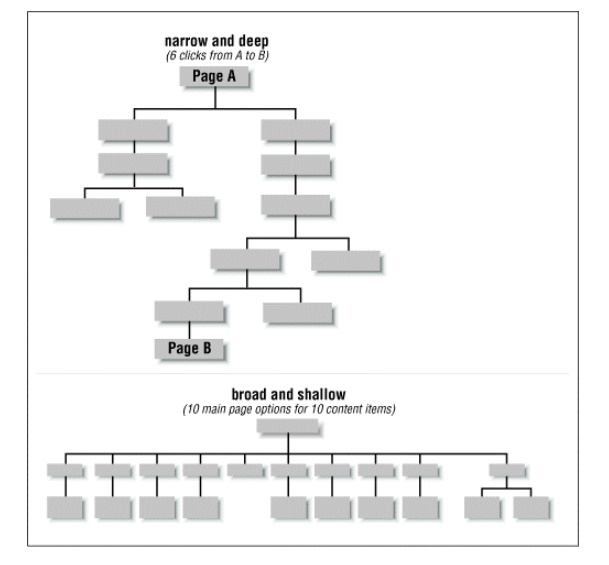

Second, it is important to consider the

balance between breadth and depth in your information hierarchy. Breadth refers

to the number of options at each level of the hierarchy. Depth refers to the

number of levels in the hierarchy. If a hierarchy is too narrow and deep, users

have to click through an inordinate number of levels to find what they are

looking for (see Figure 3.11). If a hierarchy

is too broad and shallow, users are faced with too many options on the main

menu and are unpleasantly surprised by the lack of content once they select an

option.

Figure 3.11. In the narrow and deep hierarchy, users are

faced with six clicks to reach the deepest content. In the broad and shallow

hierarchy, users must choose from ten options to reach a limited amount of

content.

In considering breadth, you should be

sensitive to the cognitive limits of the human mind. Particularly with

ambiguous organization schemes, try to follow the seven plus-or-minus two rule.2

Web sites with more than ten options on the main menu can overwhelm users.

In considering depth, you should be even more

conservative. If users are forced to click through more than four or five

levels, they may simply give up and leave your web site. At the very least,

they'll become frustrated.

For new web sites and intranets that are

expected to grow, you should lean towards a broad and shallow rather than

narrow and deep hierarchy. This approach allows for the addition of content

without major restructuring. It is less problematic to add items to secondary

levels of the hierarchy than to the main page, for a couple of reasons. First,

the main page serves as the most prominent and important navigation interface

for users. Changes to this page can really hurt the mental model they have

formed of the web site over time. Second, because of its prominence and

importance, companies tend to spend lots of care (and money) on the graphic

design and layout of the main page. Changes to the main page can be more time

consuming and expensive than changes to secondary pages.

Finally, when designing organization

structures, you should not become trapped by the hierarchical model. Certain

content areas will invite a database or hypertext-based approach. The hierarchy

is a good place to begin, but is only one component in a cohesive organization

system.

2.3 Hypertext

Hypertext is a relatively new and highly

nonlinear way of structuring information. A hypertext system involves two

primary types of components: the items or chunks of information which are to be

linked, and the links between those chunks. These components can form

hypermedia systems that connect text, data, image, video, and audio chunks.

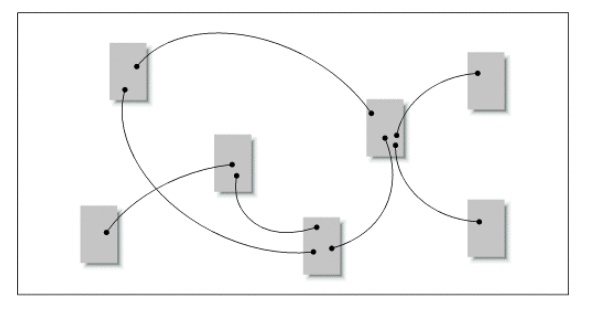

Hypertext chunks can be connected hierarchically, non-hierarchically, or both

(see Figure 3-12).

3.12. In hypertext systems, content chunks are connected

via links in a loose web of relationships.

Although this organization structure provides

you with great flexibility, it presents substantial potential for complexity

and user confusion. As users navigate through highly hypertextual web sites, it

is easy for them to get lost. It's as if they are thrown into a forest and are

bouncing from tree to tree, trying to understand the lay of the land. They

simply can't create a mental model of the site organization. Without context,

users can quickly become overwhelmed and frustrated. In addition, hypertextual

links are often personal in nature. The relationships that one person sees

between content items may not be apparent to others.

Hypertext allows for useful and creative

relationships between items and areas in the hierarchy. It usually makes sense

to first design the information hierarchy and then to identify ways in which

hypertext can complement the hierarchy.

2.4 The relational database model: A bottom-up approach

Most of us are familiar with databases. In

fact, our names, addresses, and other personal information are included in more

databases than we care to imagine. A database is a collection of records. Each

record has a number of associated fields. For example, a customer database may

have one record per customer. Each record may include fields such as customer

name, street address, city, state, ZIP code, and phone number. The database

enables users to search for a particular customer or to search for all users

with a specific ZIP code. This powerful field-specific searching is a major

advantage of the database model. Additionally, content management is

substantially easier with a database than without. Databases can be designed to

support time-saving features such as global search and replace and data

validation. They can also facilitate distributed content management, employing

security measures and version control systems that allow many people to modify

content without stepping on each others' toes.

Finally, databases enable you to repurpose the

same content in multiple forms and formats for different audiences. For

example, an audience-oriented approach might benefit from a context-sensitive

navigation scheme in which each audience has unique navigation options (such as

returning to the main page of that audience area). Without a database, you

might need to create a separate version of each HTML page that has content

shared across multiple audiences. This is a production and maintenance

nightmare! In another scenario, you might want to publish the same content to

your web site, to a printed brochure, and to a CD-ROM. The database approach

supports this flexibility.

However, the database model has limitations.

The records must follow rigid rules. Within a particular record type, each

record must have the same fields, and within each field, the formatting rules

must be applied consistently across records. This highly structured approach

does not work well with the heterogeneous content of many web sites. Also,

technically it's not easy to place the entire contents (including text,

graphics, and hypertext links) of every HTML page into a database. Such an

approach can be very expensive and time consuming.

For these reasons, the database model is best

applied to subsites or collections of structured, homogeneous information

within a broader web site. For example, staff directories, news release

archives, and product catalogs are excellent candidates for the database model.

2.5 Designing databases

Typically, the top-down process of hierarchy

design will uncover content areas that lend themselves to a database-driven

solution. At this point, you will do well to involve a programmer, who can help

not only with the database implementation but with the nitty-gritty data

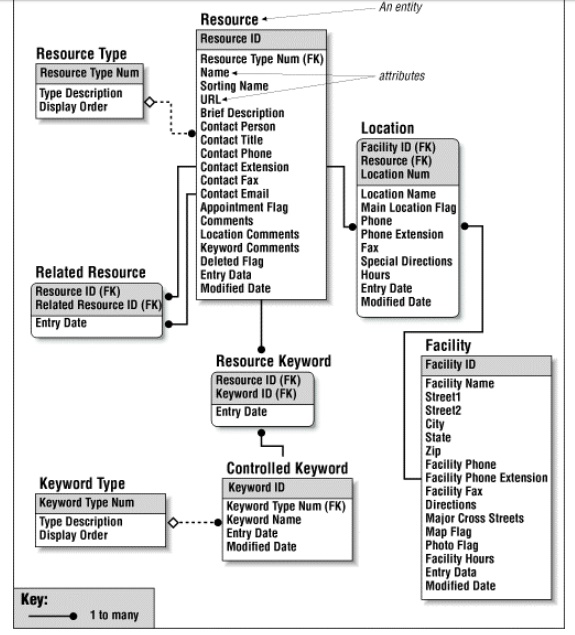

modeling issues as well (see Figure 3.13).

Figure 3.13. This entity relationship diagram (ERD)

shows a structured approach to database design. We see that entities (e.g.,

Resource) have attributes (e.g., Name, URL). Ultimately, entities and

attributes become records and fields in the database. An ERD also shows

relationships between entities. For example, we see that each resource is

available at one or more locations. The ERD is used to visualize and refine the

data model, before design and population of the database. (This entity

relationship diagram courtesy of InterConnect of Ann Arbor, a technical

consulting and development firm.)

Within each of the content areas identified as

candidates for a database-driven solution, you will need to begin a bottom-up

approach aimed at identifying the content and structure of individual record

types.

For example, a staff directory may have one

record for each staff member. You will need to identify what information will

be made available for each individual. Some fields such as name and office

phone number may be required. Others such as email address and home phone

number may be optional. You may decide to include an expertise field that

includes keywords to describe the skills of that individual. For fields such as

this, you will need to determine whether or not to define a controlled

vocabulary.

A controlled vocabulary specifies the

acceptable terms for use in a particular field. It may also employ scope notes

that define each term.

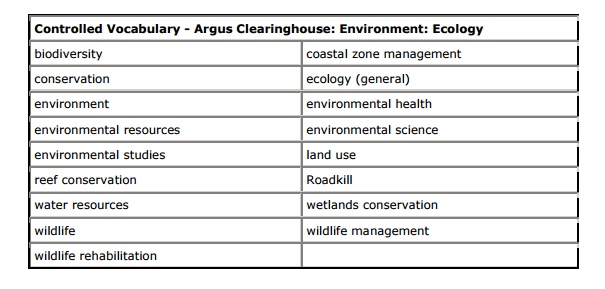

For example, the table below lists the

controlled vocabulary for keywords in the ecology area of the Argus

Clearinghouse web site (see http://www.clearinghouse.net).

The scope notes explain that ecology is "the branch of biology dealing

with the relation of living things to their environments." (See Figure 5.2 for an example of scope notes in action.)

This information is useful for the staff who index resources and the users who

navigate the web site.

Use of a controlled vocabulary imposes an

important degree of consistency that supports searching and browsing. Once

users understand the controlled vocabulary, they know that a search on biodiversity should retrieve all

relevant documents. They do not also need to try biological diversity. In addition, this consistency allows you to

automatically generate browsable indexes. This is a great feature for users, is

not very difficult to implement, and is extremely efficient from a site

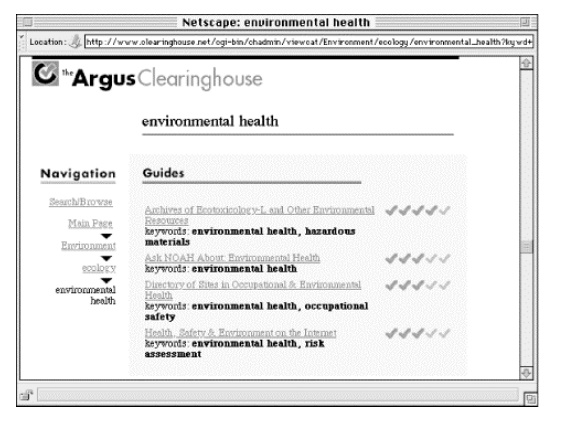

maintenance perspective (see Figure 3.14).

Figure 3.14. You can leverage a controlled vocabulary to

automatically generate browsable indexes. In this example, after selecting

Environmental Health from a menu of acceptable terms in the Ecology category,

the user is presented with a list of relevant resources. These resources have

been manually indexed according to the controlled vocabulary.

However, creating and maintaining a controlled

vocabulary is not a simple task. In many cases, complementing a simple

controlled vocabulary that divides the items into broad categories with an

uncontrolled keyword field provides a good balance of structure and

flexibility. (For more on creating controlled vocabularies, see Section 5.4.1.3 in Chapter 5.)

Once you've constructed the record types and

associated controlled vocabularies, you can begin thinking about how users

should be able to navigate this information. One of the major advantages of a

database-driven approach is the power and flexibility it affords for the design

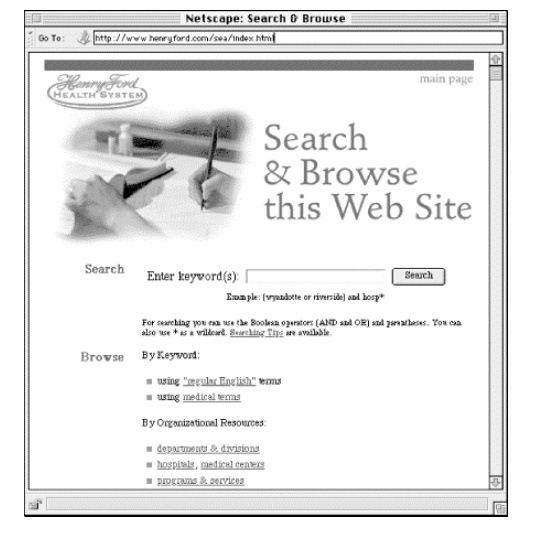

of searching and browsing systems (see Figure 3.15). Every field presents an additional way to browse or

search the directory of records.

Figure 3.15. A database of organizational resources

brings power and flexibility to the Henry Ford Health System web site. Users

can browse by organizational resource or keyword, or perform a search against

the collection of records. The browsing indexes and the records themselves are

generated from the database. Site-wide changes can be made at the press of a

button. This flexibility is made possible by a database-driven approach to

content organization and management.

The database-driven approach also brings

greater efficiency and accuracy to data entry and content management. You can

create administrative interfaces that eliminate worry about HTML tags and

ensure standard formatting across records through the use of templates. You can

integrate tools that perform syntax and link checking. Of course, the search

and browse indexes can be rebuilt automatically after each addition, deletion,

or modification.

Content databases can be implemented in a

variety of ways. The database management software can be configured to produce

static HTML pages in batch mode or to generate dynamic HTML pages on-the-fly as

users navigate the site. These implementation decisions will be influenced by

technical performance issues (e.g., bandwidth and CPU constraints) and have

little impact upon the architecture.

Related Topics