Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Physician–Patient Relationship

Formation of the Physician–Patient Relationship

Formation of the Physician–Patient

Relationship

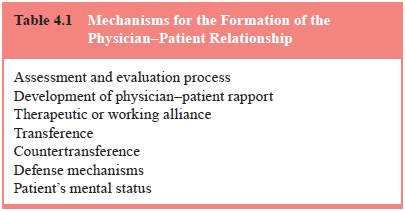

Assessment and Evaluation

The physician–patient relationship develops during

the assessment and evaluation of the patient. The patient observes the

thorough-ness and sensitivity with which the physician collects informa-tion,

performs the physical examination, and explains needed tests. At each step, the

physician’s clarification of the treatment goals and interventions either builds

up the patient’s expectation of help and feelings of safety or creates

increasing disease for the patient. In many aspects and, in particular, in the

physician’s compassion and patience, he/she is like a good teacher,

estab-lishing the context in which learning and growth may occur and anxiety

decrease (Banner and Cannon, 1997). Alertness to the patient’s fears and

misunderstandings of the evaluation process can minimize unnecessary

disruptions of the relationship and provide information on the patient’s

previous experiences with medical care and important authority figures. These

past expe-riences form the patient’s present expectations of either help or

disappointment (Smith and Thompson, 1993) (Table 4.1).

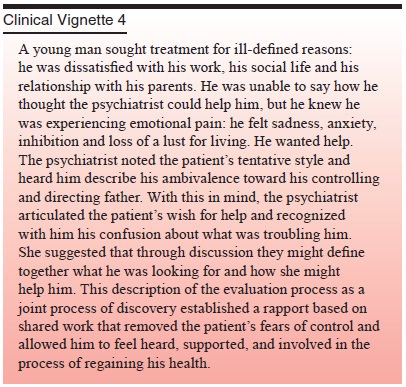

Rapport

Early in the relationship between a psychiatrist

and a patient, the patient requests help with his or her pain, uncertainty, or

discom-fort. The psychiatrist initiates the “contract” of the relationship by

acknowledging the patient’s pain and offering help. In this action, the

psychiatrist has recognized the patient’s ill-health and acknowledged the need

for and possibility of removing the dis-ease or illness. In this first stage of

the development of rapport, the way of relating between the physician and the

patient, the physician–patient relationship has begun to organize the

interac-tions. Through the physician’s and the patient’s shared recogni-tion of

the patient’s pain, the basis for rapport – a comfortable pattern of working

together – is established.

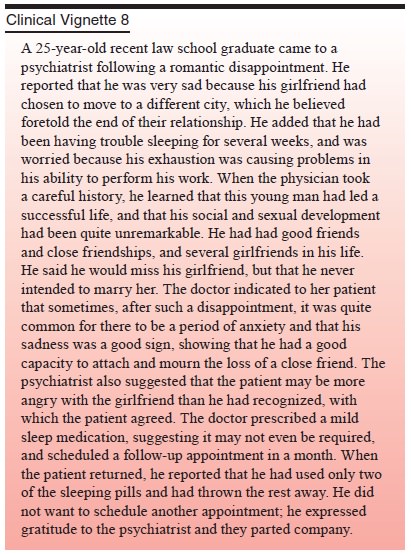

The psychiatrist’s ability to empathize, to understand in feeling terms every patient’s subjective experience, is important to the development of rapport. Empathy is particularly impor-tant in complex interpersonal behavioral problems in which the environment (family, friends, caretakers) may wish to expel the patient, and the patient has therefore lost hope. Suicidal patients, adolescents involved in intense family conflicts and patients in conflict with their medical caregivers can often be convinced to cooperate with the evaluation only when the psychiatrist has shown accurate empathy early in the first meeting with the pa-tient. When the physician acknowledges the patient’s pain, the patient feels less alone and inevitably more hopeful (Marziali and Alexander, 1991). This rapport establishes a set of principles of and expectations for the physician–patient interaction. On this basic building block more elaborate goals and responsibilities of the patient can be developed.

The Therapeutic or Working Alliance

For a patient to trust and work closely with a

physician it is essential that there be a reality-based relationship outside

the conflicted ones for which the patient is seeking help (Rawn, 1991;

Friedman, 1969). With more disturbed patients considerable skill is required of

the physician to reach this reality-based part of the patient and decrease the

patient’s fears and expectations of at-tack or humiliation. Even for healthy

patients, the physician must bridge the gap between the patient and the

physician that is al-ways present because of their different backgrounds and

percep-tions of the world. This gap is an expectable result of differences

between the physician’s and the patient’s culture, gender, ethnic background,

socioeconomic class, religion, age, or role in the physician–patient

relationship. The experienced physician makes communication across the gap seem

effortless, using a different “language” for each patient. The student often

sees this as an art rather than as a skill to be learned.

The therapeutic alliance is extremely important in

times of crisis such as suicidality, hospitalization and aggressive be-havior.

But it is also the basis of agreement about appointments, fees and treatment

requirements. In psychiatric patients, this core component of the

physician–patient relationship can be disturbed and requires careful tending.

Frequently, the psychiatrist may feel that he or she is “threading a needle” to

reach and maintain the therapeutic alliance while not activating the more

disturbed elements of the patient’s patterns of interpersonal relating.

The therapeutic or working alliance must endure in

spite of what may, at times, be intense, irrational, delusional,

charac-terologic, or transference-based feelings of love and hate. The working

alliance must outweigh or counterbalance the distorted components of the

relationship. It must provide a stable base for the patient and the physician

when the patient’s feelings or behaviors may impair reflection and cooperation.

The working alliance embodies the mutual responsibilities both physician and

patient have accepted to restore the patient’s health. Likewise, the working

alliance must be strong enough to ensure that thetreatment goes forward even

when both members of the dyad may doubt that it can. The alliance requires a

basic trust by the patient that the physician is working in his or her best

interests, despite how the patient may feel at a given moment. Patients must be

taught to be partners in the healing process and to rec-ognize that the physician

is a committed partner in that process as well. The development of common goals

fosters the physician and patient seeing themselves as having reciprocal

responsibili-ties: the physician to work in a physician-like fashion to

pro-mote healing; the patient to participate actively in formulating and

supporting the treatment plan, “trying on” more adaptive behaviors in the

chosen mode of treatment, and taking respon-sibility for his or her actions to

the extent possible (Ursano and Silberman, 1988).

Important to the reality-based relationship with

the pa-tient is the physician’s ability to recognize and acknowledge the

limitations of her or his knowledge and to work collaboratively with other

physicians. When this happens, patients are most often appreciative, not

critical, and experience a strengthening of the alliance because of the

physician’s commitment to finding an an-swer. When a patient loses confidence

in the physician, it is of-ten because of unacknowledged shortcomings in the

physician’s skills. The patient may lose motivation to maintain the alliance

and seek help elsewhere. Alternatively, the patient may seek no help.

Transference and Countertransference

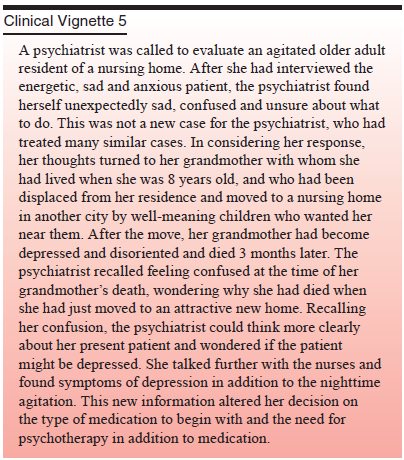

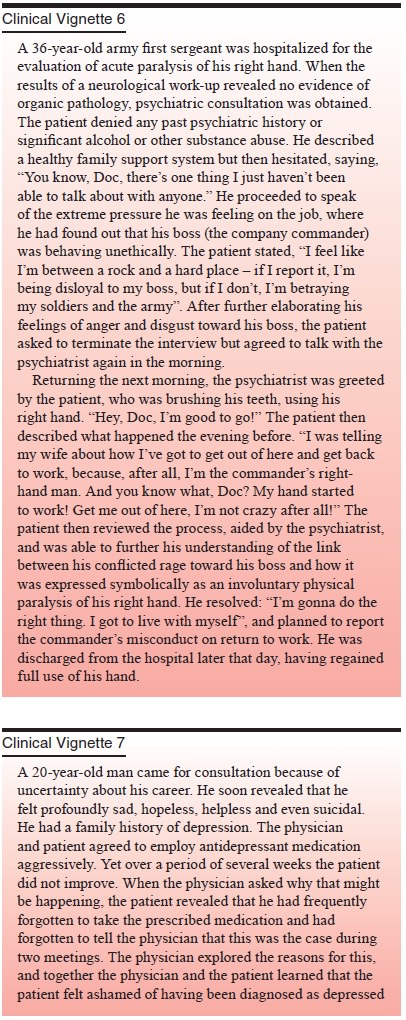

Transference is the tendency we all have to see

someone in the present as being like an important figure from our past (Freud,

1958). This process occurs outside our conscious awareness; it is probably a

basic means used by the brain to make sense of current experience by seeing the

past in the present and limit-ing the input of new information. Transference is

more common in settings that provoke anxiety and provide few cues to how to

behave – conditions typical of a hospital. Transference influences the

patient’s behavior and can distort the physician–patient rela-tionship, for

good or ill (Adler, 1980).

Although transference is a distortion of the

present reality, it is usually built around a kernel of reality that can make

it diffi-cult for the inexperienced clinician to recognize rather than react to

the transference. The transference can be the elaboration of an accurate

observation into the “total” explanation or the major evidence of some expected

harm or loss. Often the physician may recognize transference by the pressure

she or he feels to respond in a particular manner to the patient, for example, always

to stay longer or not abruptly leave the patient (Sandler et al., 1973).

Transference is ubiquitous. It is a part of

day-to-day experience, although its operation is outside conscious aware-ness.

Recognizing transference in the physician–patient relation-ship can aid the

physician in understanding the patient’s deeply held expectations of help,

shame, injury, or abandonment that derive from childhood experiences.

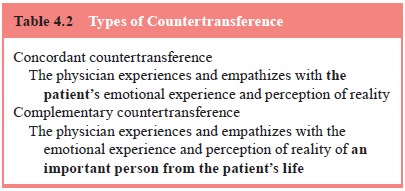

Transference reactions, of course, are not confined

to the patient; the physician also superimposes the past on the present. This

is called countertransference, the physician’s transference to the patient

(Table 4.2). Countertransference usually takes one of two forms: concordant

countertransference, in which one empathizes with the patient’s position; or

complementary coun-tertransference, in which one empathizes with an important

figure from the patient’s past (Racker, 1968). For example, concordant

countertransference would be evident if a patient were describing an argument

with his or her boss, and the psychiatrist, perhaps after a disagreement with

the psychiatrist’s own supervisor and without having collected detailed

information from the patient, felt, “Oh yeah, what a terrible boss”. Similarly,

complementary countertransference would be evident if the same psychiatrist

felt, “This person (the patient) does not work very hard, no wonder the boss is

dissatisfied,” and felt angry with the patient as well. Paying close attention

to our personal reactions while refraining from immediate action can inform us

in an experien-tial manner about subtle aspects of the patient’s behavior that

we may overlook or not appreciate. In the preceding example, the psychiatrist

with the concordant countertransference might be identifying with the patient’s

subtle need to fight with authority. The psychiatrist with the complementary

countertransference might have identified with the patient’s boss, seeing only

the patient’s more passive wishes.

Countertransference occurs in all “sizes and

shapes”, more or less mixed with the physician’s past but often greatly

influenc-ing the physician–patient relationship. The wish to save or rescue a

patient is commonly experienced and indicates a need to look for

countertransference responses. When a patient is seriously ill, such as with

cancer, we may increasingly want to treat the patient more aggressively, with

procedures that may hold little hope, create substantial pain, and perhaps even

be against the patient’s wishes. The physician’s feelings of loss of a valued per-son

(in the present and as a reminder of the past) or feelings of failure (loss of

the physician’s own power and ability) can often fuel such reactions. More

subtle factors, such as the effects of being overworked, can result in

unrecognized feelings of depri-vation leading to unspoken wishes for a patient

to quit treatment. When these feelings appear in subtle countertransference

reac-tions, such as being late to appointments, becoming tired in an hour, or

being unable to recall previous material, they can have powerful effects on the

patient’s wish to continue treatment.

Major developmental events in physicians’ lives can

also influence their perceptions of their patients. When a psychiatrist is

expecting the birth of a child, she or he may be overly sensitive to or ignore

the concerns of a patient worried about a significant illness in the patient’s

child. Similarly, a physician with a dying parent or spouse may be unable to

empathize with a patient’s concerns about loss of a job, feeling that it is trivial.

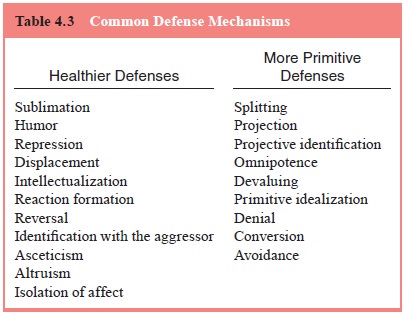

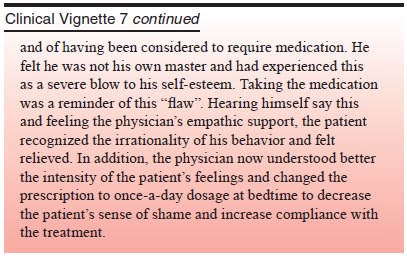

Defense Mechanisms

All people, including patients, employ mechanisms

of defense to protect themselves from the painful awareness of feelings and

memories that can provoke overwhelming anxiety. Defense mechanisms are specific

cognitive processes: ways of thinking that the mind employs to avoid painful

feelings (Freud, 1966). They are often characteristic of a person and form a

style of

cognition (Shapiro, 1965). Common defense

mechanisms include projection, repression, displacement, intellectualization,

humor, suppression and altruism (Table 4.3).

Defense mechanisms may be more or less mature

depend-ing on the degree of distortion of reality and interpersonal dis-ruption

to which they lead. This patterning of feelings, thoughts and behaviors by

defense mechanisms is involuntary and arises in response to perceptions of

psychic danger (Vaillant, 1992). The patient’s characteristic defense

mechanisms, the cognitive proc-esses used to lower anxiety and unpleasant

feelings, can greatly affect the physician–patient relationship. Defense

mechanisms operate all the time; however, in times of high anxiety, such as in

a hospital or during a life crisis, patients may become much less flexible in

the defenses they use and may revert to using less mature defenses.

Mental Status of the Patient

The patient’s mental status is a major determinant

of the forma-tion and nature of the relationship with the physician. A young,

healthy patient with an acute disorder has different needs and expectations

than a somewhat older person who comes for help with a condition that has been

present for a number of years. Both differ from the older adult who comes to

the physician expecting that the future will be filled with physical and

emotional losses.

The patient’s mental status in this case was the focus of and major factor in the structure of a long psychotherapy that greatly assisted the rehabilitation of interpersonal skills and the understanding of his cognitive limitations and newly changed cognition. The ability to work with an empathic listener while confronting limitations and feelings of shame and embarrass-ment is a special opportunity of the well-formed doctor–patient relationship.

Related Topics