Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Couples Therapy

Evaluation of the Couple

Evaluation

of the Couple

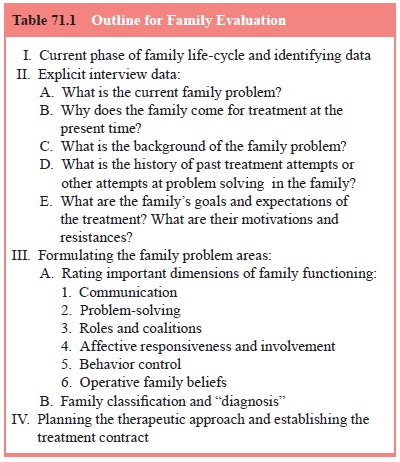

The

evaluation of a couple involves obtaining data on the current point in the

marital and/or family life-cycle,why the couple ap-proaches for assistance at a

particular time, and each partner’s view of the marital or relationship problem

(Table 71.1). Often the couple’s therapist will hold one individual session

with each partner after the first or second conjoint session. This gives each

partner an opportunity to divulge information that might other-wise not be

obtainable. Issues of confidentiality need to be care-fully addressed.

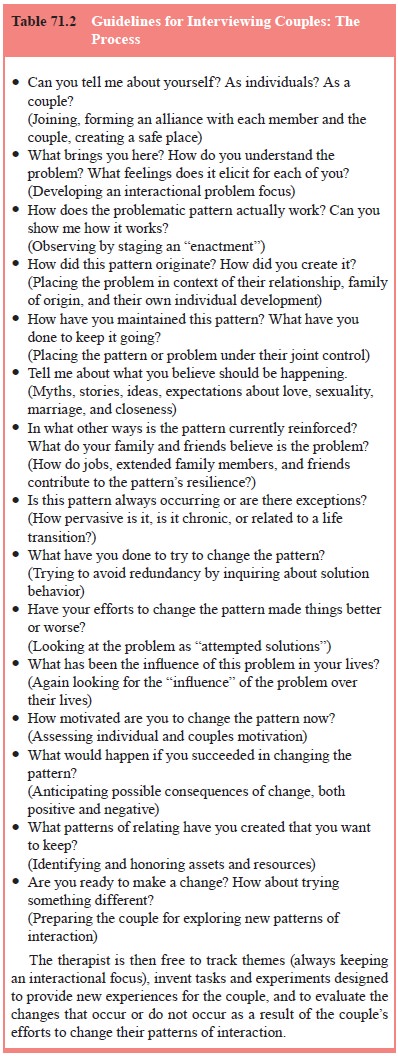

In

formulating the marital difficulties, the evaluator will want to consider the

couple’s communication, problem-solving, roles, affective expression and

involvement, and behavioral ex-pression, especially in sexual and aggressive

areas. The clinician will also want to evaluate gender roles, cultural and

racial issues, and power inequities resulting from gender, class, age, or

finan-cial status. It is critical to ask about alcohol, health and

reproduc-tive issues, and violence (Table 71.2).

Even if

the partners do not mention their children as a problem, it is wise to spend

some time developing a sense of how the children are doing, is there a favored

child or problem with any of them, and whether the children are being pulled

into marital conflicts. At times children can be the source of a cou-ple’s

conflict and at other times they may function as the glue that keeps the

relationship together. If a large part of the couple’s difficulty centers

around issues with the children, family therapy may be the preferred treatment

modality.

Other areas deserving special attention include each spouse’s commitment to the marital union and the couple’s sex-ual life. Assessment is complicated when one spouse is keeping commitment doubts or extramarital sex a secret. Conjoint and individual sessions with each partner may be needed. When infidelity or serious commitment questions arise, the therapist and couple must address whether or not the couple should stay together.

Genograms for Evaluation

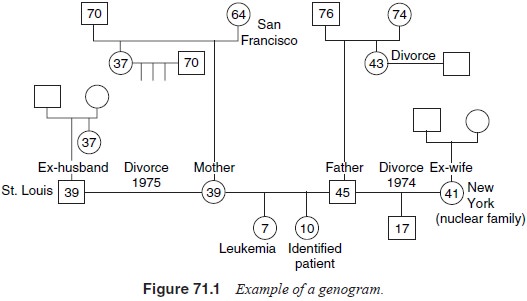

A helpful

device when evaluating a couple is the use of a ge-nogram. The therapist can

collect and organize historical data

through

the use of a genogram, the three-generational family tree depicting the

family’s patterns regarding either specific problems or general family functioning.

The genogram technique suggests possible connections between present family

events and the prior experiences that family members have shared (e.g.,

regarding the management of serious illnesses, losses and other critical

transi-tions), thereby placing the presenting problem in a historical con-text

(Shorter, 1977; McGoldrick and Gerson, 1985). Constructing a genogram early on

in treatment can provide a wealth of data that frequently offers clues about

pressures, expectations and hopes regarding the marriage. This pictorial way of

gathering a history allows each member of the couple to learn about beliefs or

themes that characterize his/her family background. An example of a genogram

can be seen in Figure 71.1.

Assessment of Concomitant Psychiatric Illness

Having a

spouse with a serious Axis I disorder, such as anxiety disorder, mood disorder,

or substance abuse puts realistic strain on the marital relationship. The

marital interaction prior to, during and following the onset of the symptoms in

the spouse is influenced by numerous factors and is quite variant across dyads.

It is incorrect to assume that in all cases the interaction between the spouses

brought on, or caused, or even helped trigger the mental disorder and symptoms

in the other. Whatever the symptoms in one spouse, the relationship of symptoms

to the marital interaction is on a continuum and can take any one of the

following forms:

·

The marital interaction neither causes the symptoms

nor stresses the psychologically vulnerable spouse.

·

The marital interaction does not stress the

vulnerable indi-vidual but following onset of symptoms the marital interac-tion

declines and becomes dysfunctional, thus causing more distress.

·

The marital interaction acts as a stressor that

contributes to the onset of symptoms in a vulnerable spouse.

·

The symptoms can be explained totally as under the

con-trol and function of the interactional patterns between the spouses.

The

therapist meeting a new couple therefore can entertain a range of different

ideas that may help illuminate and explain their distressing circumstances. The

Axis I condition can be a useful focus and often is what brings the couple in

for help.

Evaluation of Sexual Disorders

A careful

evaluation of the couple’s total interactions needs to be done by the therapist

as well as a physical assessment when dysfunction is present. When it appears

that the basic marriage is a sound one, but that the couple suffers from

specific sexual diffi-culties (which may also lead to various secondary marital

conse-quences), the primary focus might be sex therapy per se. In many cases,

however, specific sex therapy cannot be carried out until the relationship

between the two partners has been improved in other respects; indeed, the

sexual problems may clearly be an outgrowth of the marital difficulties. When

marital problems are taken care of, the sexual problems may readily be

resolved. It may be difficult to disentangle marital from sexual problems or to

decide which came first. The priorities for therapy may not always be clear.

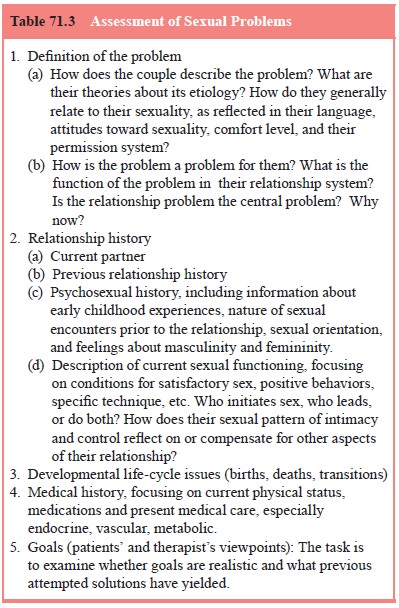

Specific

techniques are available which have been devised for eliciting a sexual history

and for evaluating sexual function-ing. The marital therapist should become

familiar with these ideas and obtain experience in their utilization. A

systemic as-sessment of sexual difficulties includes, at the minimum, the

fol-lowing details as listed in Table 71.3.

In

addition, in couples where there is any possibility that the problems may have

an organic component, it is crucial to in-sist on a medical work-up. This is

particularly key for men, for whom small physiological changes in potency may

produce anxi-ety that exacerbates the problem.

The

taking of an intimate sexual history of husband and wife should, of course, be

conducted with the couple without children present. The process of taking a

sexual history should be handled with care and regard for each person’s level

of comfort.

What type

of language should be used when discussing sexual topics? Obviously, one should

not use terms that would be offensive or uncomfortable for either the therapist

or the couple. At the same time, care must be taken to avoid using bland

gener-alities which fail to elicit specific sexual information. Frankness is

encouraged, and when there is vagueness, the therapist needs to follow-up with

more specific questions.

Taking a sexual history of lesbian and gay couples may be particularly difficult for a heterosexual therapist, either because of discomfort with homosexuality or lack of knowledge of ho-mosexual norms and mores. In addition, the couple may have a wider or different set of sexual practices than the therapist is used to (of course, this may be true with heterosexual couples as well). Therapists have the options of educating themselves about homo-sexual sexuality, either by reading books available in mainstream bookstores about gay and lesbian life, and/or asking the couple about their own and other common practices. If the therapist is very anxious in this situation, he/she must decide when the ther-apy is not proving effective and if he/she should refer to another therapist. Gay and lesbian couples may present with any of the dysfunctions or dissatisfactions of heterosexual couples.

Related Topics