Communalism in Nationalist Politics | History - Emergence of the All India Hindu Mahasabha | 12th History : Chapter 6 : Communalism in Nationalist Politics

Chapter: 12th History : Chapter 6 : Communalism in Nationalist Politics

Emergence of the All India Hindu Mahasabha

Emergence of the All India Hindu Mahasabha

In the

wake of the formation of the Muslim League and introduction of the Government

of India Act of 1909, a move to start a Hindu organisation was in the air. In

pursuance of the resolution passed at the fifth Punjab Hindu Conference at

Ambala and the sixth conference at Ferozepur, the first all Indian Conference

of Hindus was convened at Haridwar in 1915. The All India Hindu Mahasabha was

started there with headquarters at Dehra Dun. Provincial Hindu Sabhas were

started subsequently in UP, with headquarters at Allahabad and in Bombay and

Bihar. While the sabhas in Bombay and Bihar were not active, there was little

response in Madras and Bengal.

Predominantly

urban in character, the Mahasabha was concentrated in the larger trading cities

of north India, particularly in Allahabad, Kanpur, Benares, Lucknow and Lahore.

In United Province, Bihar the Mahasabha, to a large extent was the creation of

the educated middle class leaders who were also activists in the Congress. The

Khilafat movement gave some respite to the separatist politics of the

communalists. As a result, between 1920 and 1922, the Mahasabha ceased to

function.

The entry

of ulema into politics led Hindus to

fear a revived and aggressive Islam. Even important Muslim leaders like Ali

brothers had always been Khilafatists first and Congressmen second. The power

of mobilisation on religious grounds demonstrated by the Muslims during the Khilafat

movement motivated the Hindu communalists to imitate them in mobilising the

Hindu masses. Suddhi movement was not a new phenomenon but in the post-Khilafat

period it assumed new importance. In an effort to draw Hindus into the boycott

of the visit of Prince of Wales in 1921, Swami Shradhananda tried to revive the

Mahasabha by organizing cow-protection propaganda.

Before the World War I, Britain had promised to safeguard the

interests of the Caliph as well the Kaaba (the holiest seat of Islam). But after

Turkey’s defeat in the War, they refused to keep their word. The stunned Muslim

community showed its displeasure to the British government by starting the

Khilafat movement to secure the Caliphate in Turkey.

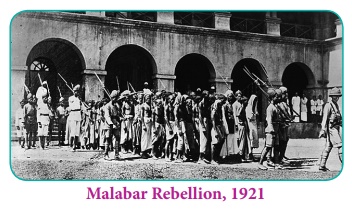

The

bloody Malabar rebellion of 1921, where Muslim peasants were pitted against

both the British rulers and Hindu landlords, gave another reason for the

renewed campaign of the Hindu Mahasabha. Though the outbreak was basically an

agrarian revolt, communal passion ran high in consequence of which Gandhi

himself viewed it as a Hindu-Muslim conflict. Gandhi wanted Muslim leaders to

tender a public apology for the happenings in Malabar.

(a) Communalism in United Provinces (UP)

The

suspension of the non-cooperation movement in 1922 and the abolition of the

Caliphate in 1924 left the Muslims in a state of frustration. In the aftermath

of Non-Co-operation movement, the alliance between the Khilafatists and the

Congress crumbled. There was a fresh spate of communal violence, as Hindus and

Muslims, in the context of self-governing institutions created under the Act of

1919, began to stake their political claims and in the process vied with each

other to acquire power and position. Of 968 delegates attending the sixth

annual conference of the Hindu Mahasabha in Varanasi in August 1923, 56.7 came

from the U.P. The United Provinces (UP), the Punjab, Delhi and Bihar together

contributed 86.8 % of the delegates. Madras, Bombay and Bengal combined sent

only 6.6% of the delegates. 1920s was a trying period for the Congress. This

time the communal tension in the United Province was not only due to the zeal

of Hindu and Muslim religious leaders, but was fuelled by the political

rivalries of the Swarajists and Liberals.

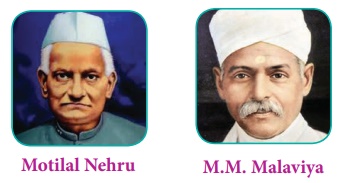

In

Allahabad, Motilal Nehru and Madan Mohan Malaviya confronted each other. When

Nehru’s faction emerged victorious in the municipal elections of 1923,

Malaviya’s faction began to exploit religious passions. The District Magistrate

Crosthwaite who conducted the investigation reported: ‘The Malavia family have

deliberately stirred up the Hindus and this has reacted on the Muslims.’

(b) The Hindu Mahasabha

In the

Punjab communalism as a powerful movement had set in completely. In 1924 Lala

Lajpat Rai openly advocated the partition of the Punjab into Hindu and Muslim

Provinces. The Hindu Mahasabha, represented the forces of Hindu revivalism in

the political domain, raised the slogan of ‘Akhand Hindustan’ against the

Muslim League’s demand of separate electorates for Muslims. Ever since its

inception, the Mahasabha’s role in the freedom struggle has been rather

controversial. While not supportive of British rule, the Mahasabha did not

offer its full support to the nationalist movement either.

Since the

Indian National Congress had to mobilize the support of all classes and

communities against foreign domination, the leaders of different communities

could not press for principle of secularism firmly for the fear of losing the

support of religious-minded groups. The Congress under the leadership of Gandhi

held a number of unity conferences during this period, but to no avail.

(c) Delhi Conference of Muslims and their Proposals

One great

outcome of the efforts at unity, however, was an offer by the Conference of

Muslims, which met at Delhi on March 20, 1927 to give up separate electorates

if four proposals were accepted. 1. the separation of Sind from Bombay 2.

Reforms for the Frontier and Baluchistan 3. Representation by population in the

Punjab and Bengal and 4. Thirty-three per cent seats for the Muslims in the

Central Legislature.

Motilal

Nehru and S. Srinvasan persuaded the All India Congress Committee to accept the

Delhi proposals formulated by the Conference of the Muslims. But communalism

had struck such deep roots that the initiative fell through. Gandhi commented

that the Hindu-Muslim issue had passed out of human hands. Instead of seizing

the opportunity to resolve the tangle, the Congress chose to drag its feet by

appointing two committees, one to find out whether it was financially feasible

to separate Sind from Bombay and the other to examine proportional

representation as a means of safeguarding Muslim majorities. Jinnah who had taken

the initiative to narrow down the breach between the two, and had been hailed

the ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity by Sarojini, felt let down as the Hindu

Mahasabha members present at the All Parties Convention held in Calcutta in

1928 rejected all amendments and destroyed any possibility of unity.

Thereafter, most of the Muslims were convinced that they would get a better

deal from Government rather than from the Congress.

Expressing anguish over the development of sectarian

nationalism, Gandhi wrote, ‘There are as many religions as there are

individuals, but those who are conscious of the spirit of the nationality do

not interfere with one another’s religion. If Hindus believe that India should

be peopled only by Hindus, they are living in a dream land. The Hindus, the

Sikhs, the Muhammedans, the Parsis and the Christians who have made their

country are fellow countrymen and they will have to live in unity if only for

their interest. In no part of the world are one nationality and one religion

synonymous terms nor has it ever been so in India.’

(d) Communal Award and its Aftermath

The

British Government was consistent in promoting communalism. Even the delegates

for the second Round Table Conference were chosen on the basis of their

communal bearings. After the failure of the Round Table Conferences, the British

Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald announced the Communal Award which further

vitiated the political climate.

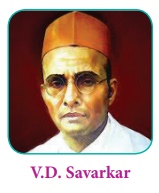

The

Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (R.S.S.) founded in 1925 was expanding and its

volunteers had shot upto 1,00,000. K.B. Hedgewar, V.D. Savarkar and M.S.

Golwalker were Hindu Rashtra and openly advocated that ‘the non-Hindu people in

Hindustan must adopt the Hindu culture and language... they must cease to be

foreigners or may stay in the country wholly subordinated to the Hindu Nation

claiming nothing.' V.D. Savarkar asserted that ‘We Hindus are a Nation by

ourselves’. Though the Congress had forbidden its members from joining the

Mahasabha or the R.S.S. as early as 1934, it was only in December 1938 that the

Congress Working Committee declared Mahasabha membership to be a

disqualification for remaining in the Congress.

Related Topics