Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Pharmacotherapies for Substance Abuse

Drug Treatment of Withdrawal Syndromes

Drug

Treatment of Withdrawal Syndromes

Some

general principles apply to drug treatments for specific withdrawal syndromes:

When

monitoring treatment:

·

Set clear targets.

·

Make serial assessments and modify based on these

assessments.

Psychosocial

factors:

·

Prepare the patient.

·

Emphasis on detoxification as a beginning to

treatment.

From a

pharmacologic standpoint, an ideal agent for the treat-ment of withdrawal

should have the following characteristics:

·

Efficacy in relieving the complete range of

abstinence signs and symptoms for a given type of withdrawal.

·

A relatively long duration of action and gradual

offset of effects.

·

A high degree of safety in the dosage needed to

suppress with-drawal (i.e., high therapeutic index).

·

It should be available by a variety of routes of

administration and have little abuse potential in itself.

Other

general but important aspects of detoxification are also fre-quently

overlooked:

·

Clear treatment targets should be kept in mind.

·

Structured rating scales should be used to measure

symptom severity: serial assessment of the clinical response is the best

strategy for guiding treatment and detoxification should not be conducted “on

autopilot”.

·

While protocols may offer useful guidance, orders should

be rewritten with thought and often daily.

Patients

must understand that detoxification is not a treatment for addiction but the

beginning of treatment for the chronic problems associated with substance

dependence. They should know what they will experience and they should if at

all possible be engaged in the effort to relieve their symptoms as safely as

possible and with greatest effectiveness. They need to understand, however,

that they are likely to experience some distress. Detoxification can be carried

out on an outpatient basis for patients who are in relatively good health and

have sufficiently stable social support.

Alcohol Withdrawal

Alcohol

withdrawal is a medical emergency and can be life-threatening without

appropriate supportive medical treatment.

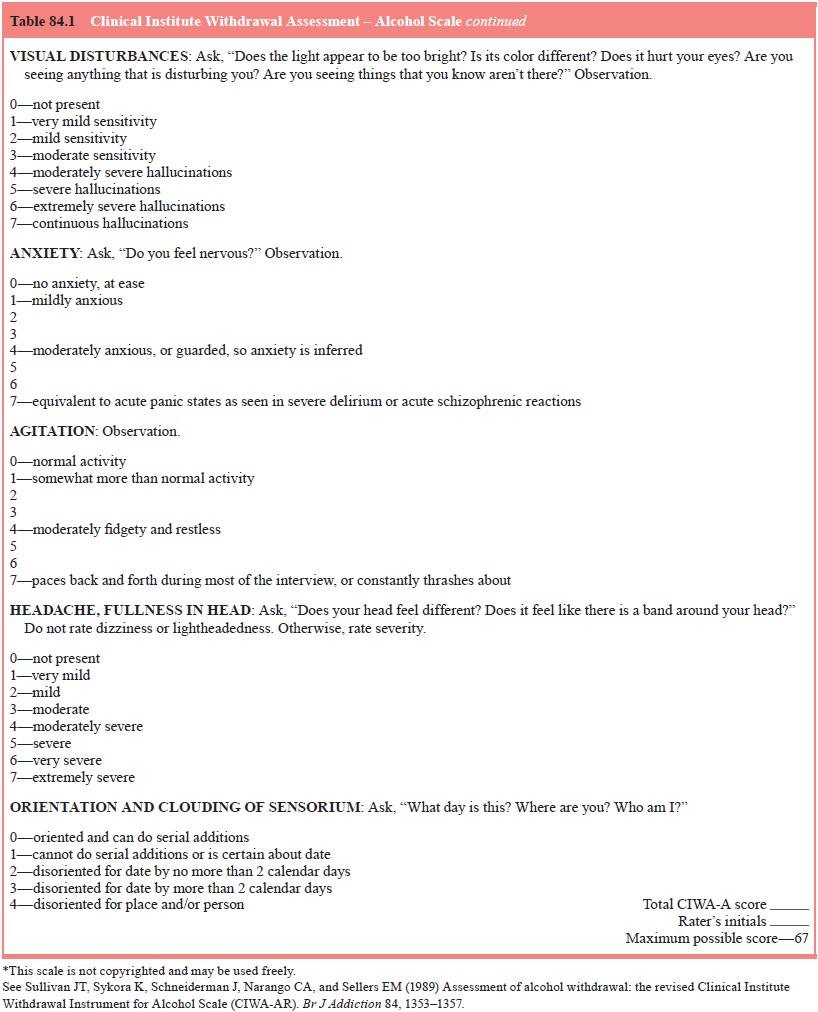

The risk

of progressing from uncomplicated withdrawal to seizures or delirium should be

greatly reduced by proper man-agement. Patients should be assessed

systematically when enter-ing the detoxification protocol and during the

process. A widely used but simple tool is the Clinical Institute Withdrawal

Assess-ment – Alcohol Scale (Table 84.1). Starting 6–24 hours after the last

drink, this scale should be used to assess the patient initially every 1–2

hours and at regular intervals until two consecutive scores below 8–10 are

achieved. It is then safe to end structured assessment. Scores greater than 15

are an indication for monitor-ing the patient even more closely. Scores in

between these limits should be interpreted according to clinical judgment

according to the degree of discomfort reported by the patient and their history

of withdrawal syndromes.

Undertreatment

with doses that are too low or dose inter-vals that are too long is the

commonest error in the drug treat-ment of withdrawal syndromes. However,

striking the balance between withdrawal and intoxication is not complicated

provided serial assessments are made.

Benzodiazepines

are the drugs of choice for treating alco-hol withdrawal because:

·

There is cross-tolerance with alcohol (therefore

higher than normal doses may be needed).

·

They are relatively safe compared with other

sedative-hypnotics.

·

They have been shown to reduce the frequency of

seizures and delirium.

The

benzodiazepines can be divided into two major classes according their duration

of action. Longer-acting agents, includ-ing chlordiazepoxide and diazepam,

undergo metabolic oxidation and glucuronidation. Their advantage is that blood

levels decline more slowly during the tapering process, increasing patient

com-fort and reducing the risk of seizures. The disadvantage is that, in older

patients and patients with impaired hepatic or pulmonary function, decreased

elimination may result in accumulation and toxicity. Chlordiazepoxide may be

preferred to diazepam because it may have a lower abuse potential.

Shorter-acting

agents, such as oxazepam and lorazepam, are metabolized only by

glucuronidation. Both drugs are available in oral and intravenous forms though

only lorazepam may also be administered by intramuscular injection. These

agents are more readily metabolized and eliminated by older patients and they

are less likely to accumulate and cause toxicity in patients with liver

disease. However, blood levels decline more rapidly and this may cause breakthrough

symptoms and seizures between doses.

The

treatment response should be assessed serially. Medi-cation should adjusted

according to clinical need: if signs of

withdrawal

are apparent, the dose should be increased or the dose interval reduced. Some

degree of sedation is desirable but medi-cation should be withheld if the

patient becomes over-sedated and recommenced when clinically indicated.

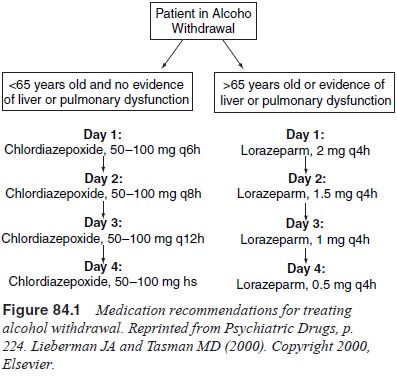

Recommendations for medication are summarized in Figure 84.1.

Hallucinations

that develop as a feature of delirium are relatively refractory to treatment

with a benzodiazepine alone. Patients who develop hallucinations despite

sedative-hypnotic substitution may be treated with adjunctive haloperidol, 2 to

5 mg.

In the

event of persistent tachycardia or hypertension, the possibility of

inadequately treated withdrawal should first be ex-cluded. This problem has

been managed successfully with beta-blockers and clonidine but while these

agents may decrease vital signs and tremor they do not prevent seizures.

An

alternative strategy is to “frontload” the patient, achieving sedation by

administering diazepam or chlordiazepox-ide every 1 to 2 hours. Because these

agents have a long elimina-tion half-life, their effects diminish slowly and

smoothly over the withdrawal period. However, careful serial assessment remains

essential while the patient is vulnerable to the complications of withdrawal.

Thiamine

is indicated for every patient with alcoholism to prevent Wernicke’s

encephalopathy and Korsakoff’s amnestic syndrome. It should be administered

immediately (typical dose 100 mg daily), before intravenous glucose. Less

urgently, nutri-tional support should include supplementation with folate 1 mg

and multivitamins. It has been suggested that magnesium sup-plementation may

prevent withdrawal seizures but there is no consensus on its use in the absence

of documented magnesium deficiency.

There are

promising reports on the use of carbamazepine and valproate in alcohol

withdrawal and they may be helpful in special circumstances. However, the

safety and efficacy of ben-zodiazepines are currently unsurpassed.

Sedative-hypnotic Withdrawal

Similar

to the treatment for alcohol withdrawal, benzodiazepine taper (as described

above) is a good choice, particularly if the patients is dependent on

benzodiazepines. Another excellent choice for substitution therapy is

phenobarbital: it has low po-tential for abuse, there is a wide margin between

therapeutic and lethal blood levels, and it has a long duration of action with

rela-tively little variation in between-dose blood levels. The symp-toms of

intoxication with phenobarbital (ataxia, slurred speech, nystagmus) are readily

observed easy and managed within a de-toxication protocol.

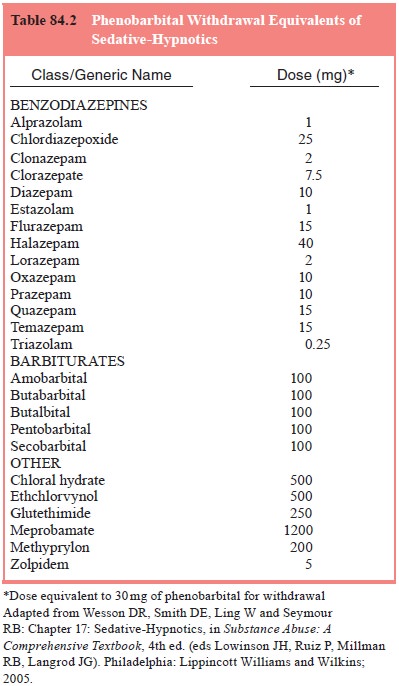

For

patients dependent on sedative-hypnotics, the first step in management if to

take a history. Information about the level of drug consumption can be

converted to “phenobarbital equiva-lents” to provide a guide to the required

dose of phenobarbital, as specified in Table 84.2.

The

number of phenobarbital equivalents is summed and administered as a

thrice-daily dose regimen. The total daily requirement of phenobarbital rarely

exceeds 500 mg even in patients with extreme dependency. The first dose of

phenobarbital may be administered as an intramuscular injec-tion if signs of

withdrawal occur before substitution therapy begins. Symptoms of withdrawal and

intoxication should be reassessed after 1 to 2 hours to determine the next dose

of phenobarbital.

The

degree of dependence can also be assessed by serial challenge with

pentobarbital at doses of 200 mg but it is not clear that this method offers

any advantage over direct substitution with phenobarbital, which is safe, rapid

and simple.

There

should be no signs of sedative-hypnotic withdrawal or phenobarbital toxicity

after 24 to 48 hours; dose reduction of phenobarbital can then be started.

Maintaining the thrice-daily dose regimen, the dose of phenobarbital should be

reduced in increments of 30 mg/day. If there is evidence of phenobarbital

toxicity (slurred speech, nystagmus, ataxia), the next dose should be withheld

and the total daily dose reduced. Conversely, if there are objective signs of

withdrawal, the total daily dose of pheno-barbital should be increased and dose

reduction delayed until the patient is once again stable.

Opiate Withdrawal

Withdrawal

from opiates may be intensely uncomfortable but, by contrast with

sedative-hypnotic withdrawal, it is not usually life-threatening for adults;

important exceptions include adults with little reserve – for example, due to

to advanced AIDS – and newborn infants. Nevertheless, reducing withdrawal

symptoms may help to engage an addict in a treatment program or facilitate the

management of another medical condition.

Methadone

is approved by the FDA for treating opiate withdrawal but states may have

different regulations governing its use and clinicians need to be aware of

local requirements. Methadone use is typically permitted for inpatient

detoxification or maintenance treatment but it cannot be prescribed to treat

opi-ate withdrawal in outpatients except as part of a licensed metha-done

maintenance treatment program.

Methadone

is administered orally and has a long duration of action. An initial dose of 15

to 20 mg may be given when signs of opiate withdrawal are seen (not merely when

craving is re-ported). An additional 5 to 10 mg may be given in 1 to 2 hours if

symptoms persist or worsen. A dose of 40 mg/day usually con-trols signs of

withdrawal well (note that this is often insufficient for the different

indication of long-term maintenance). If oral ad-ministration is impossible due

to withdrawal symptoms, doses of 5 mg may be administered by intramuscular

injection. Having reached a dose at which withdrawal symptoms are alleviated,

the dose can be tapered by 5 to 10% per day until full detoxification is

achieved.

A newly

available option for treatment of opioid with-drawal is the Schedule III opioid

partial agonist buprenorphine, which is now available for use in the office

based practice by any physician who has taken a brief training and

certification. While the use of Schedule II drugs such as methadone for the

treat-ment for opiate dependence is restricted to hospitals or specially

licensed clinics (leading to a shortage of facilities where opiate-dependent

individuals could receive appropriate treatment), the Drug Addiction Treatment

Act of 2000 introduced less stringent regulations, allowing the use of narcotic

drugs for the treatment of addiction in the office or any other health care

setting by any licensed physician who has taken a brief training course and

obtained registration, thereby increasing access to treatment. Two new

formulations of the buprenorphine (Subutex and Sub-oxone sublingual tablets)

were the first products to be approved by the FDA under this Act for the

treatment of opioid depend-ence. Subutex contains only buprenorphine in doses

of 2 or 8 mg; Suboxone also contains the opioid antagonist naloxone (0.5 and 2

mg respectively); the purpose of the naloxone is to discourage diversion of the

medication for abuse intravenously (crushing the pills and injecting them),

since naloxone is poorly absorbed after oral or sublingual administration, but

if injected would produce precipitated withdrawal.

Buprenorphine

is an excellent detoxification agent because of its long duration of action,

due to very high affinity for and very slow dissociation from opioid receptors.

Starting buprenorphine must be done carefully, because of the partial agonism.

If admin-istered too close in time to the last dose of a full agonist such as

heroin, buprenorphine will precipitate withdrawal, and the with-drawal produced

can be atypical and in rare cases has been ob-served to include delirium.

Precipitated withdrawal is more likely among patients dependent on long-acting

agonists (e.g. metha-done), or high daily doses of a shorter-acting agonist

such as heroin. Thus, when starting buprenorphine, the clinician should wait

for symptoms of opioid withdrawal to begin to appear before giving the first

dose of buprenorphine, which should be a test dose of 2 mg (Subutex 2 mg, or

Suboxone (2 mg buprenorphine/0.5 mg naloxone). If this dose is well tolerated,

administer another 2 mg one hour later, and up to 8 mg total on the first day, and

up to 16 mg on the second day. After this buprenorphine can be tapered slowly

to zero over 10 days to 2 weeks. Considerable flexibility in the taper schedule

is possible, including a much faster taper, since the slow dissociation from

receptors in itself effectively produces a taper. However, clinicians should

also be alert for the emergence of low-grade withdrawal symptoms (fatigue,

anxiety, mild flu-like physical symptoms) in the weeks after discontinuing

buprenor-phine. This subacute or protracted withdrawal can be observed after

withdrawal from any opioid drug, but can seem surprisingly with buprenorphine

because the taper phase of a buprenorphine detoxification is usually

comfortable and uneventful.

If one of

the first few doses of buprenorphine administered is followed by a rapid

worsening of withdrawal symptoms, this is precipitated withdrawal, and no

further buprenorphine should be given; at this point it is probably best to

treat with a full agonist (methadone), although one could also wait for precipitated

with-drawal to clear and full-blown opiate withdrawal (from whatever the

patient was addicted to) to emerge, after which one can try again beginning

with a test dose of 2 mg buprenorhine.

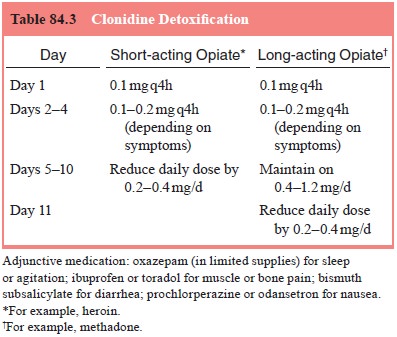

A number

of nonnarcotic medications are useful in treat-ing the symptoms of opiate

withdrawal. These include the α-adrenergic

receptor agonist and antihypertensive clonidine, which is

particularly helpful with the autonomic symptoms of withdrawal as well as the

anxiety, benzodiazepines (clonazepam is typically used), which are particularly

helpful for the anxi-ety and insomnia, antiemetics and NSAIDs for muscle aches

(oral agents such as ibuprofen, or Toradol which can be given parenterally).

Autonomic symptoms may be well controlled with clonidine alone but patients

frequently report greater subjective distress than with methadone or

buprenorphine. The role of cloni-dine is for detoxification from illegal

opiates, for example in set-tings where methadone is not allowed, or to

alleviate abstinence symptoms when a patient comes to the end of a methadone

main-tenance program. Its major side effects are hypotension (which may require

dose reduction or discontinuation) and sedation. Hypotension may be worsened by

diarrhea, or vomiting, which are common in opiate withdrawal. Patients should

be encouraged to take plenty of fluids, and sports drinks such as gatorade are

particularly helpful because they also supply electrolytes. Clo-nidine does not

address all aspects of withdrawal and it should therefore be used in

combination with the alternatives detailed above. A protocol for

clonidine-assisted detoxication is given in Table 84.3.

A

combination of clonidine with naltrexone has been used to achieve a more rapid

withdrawal, followed by maintenance treatment with naltrexone. However,

clinical experience and close monitoring of the patient is necessary to titrate

the dose of clonidine against withdrawal symptoms induced by naltrexone. The

acceptability of maintenance treatment with naltrexone to opiate addicts is

disappointing.

With

opiate detoxification, it is particularly important to consider the indications

for it, and to establish an adequate treatment plan after detoxification is

completed. Chronic opioid use induces tolerance, and detoxification reduces or

eliminates tolerance. Because of the loss of tolerance, detoxified opiate

ad-dicts are at increased risk for death from opiate overdose; doses that they

routine self-administered previously when tolerant, could now be lethal, a

problem exacerbated by the variable and sometimes high potency of illicit

heroin. In general, the risk of re-lapse following opioid detoxification is

high. Therefore, patients should be assessed for overdose risk, and those with

a history of past overdoses, or with multiple past relapses, should be

encour-aged to take agonist maintenance treatment, with methadone or

buprenorphine, rather than undergoing detoxification. For those not entering

agonist maintenance, a strong plan for psychosocial treatment is important, for

example long-term residential treat-ment or Therapeutic Community, a good

outpatient treatment program, supplemented by self-help group (Alcoholics

Anony-mous, or Narcotics Anonymous).

Related Topics