Chapter: Embedded Systems Design : Software examples

Creating software state machines

Creating software state machines

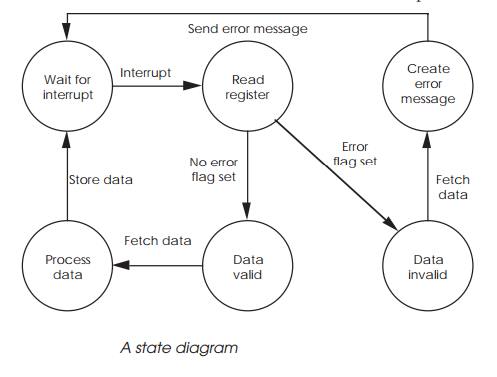

With many real-time applications, a common approach taken with software

is first to determine how the system must respond to an external stimulus and

then to create a set of state diagrams which correspond with these definitions.

With a state diagram, a task or module can only exist in one of the states and

can only make a transition to another state provided a suitable event has

occurred. While these diagrams are easy to create, the software structure can

be difficult.

One way of creating the equivalent of software state dia-grams is to use

a modular approach and message passing. Each function or state within the

system — this can be part of or a whole state diagram — is assigned to a task.

The code for the task is extremely simple in that it will do nothing and will

wait for a message to arrive. Upon receipt of the message, it will decode it

and use the data to change state. Once this has been completed, the task will

go back to waiting for further input. The processing can involve other changes

of state as well. Referring back to the example, the incoming interrupt will

force the task to come out of its waiting state and read a particular register.

Depending on the contents of that register, one of two further states can be

taken and so on until the final action is to wait for another interrupt.

This type of code can be written without using an operating system, so

what are the advantages? With a multitasking real-time operating system, other

changes of state can happen in parallel. By allocating a task to each hardware

interrupt, multiple interrupts can easily be handled in parallel. The

programmer simply codes each task to handle the appropriate interrupt and the

operating system takes care of running the multiple tasks. In addition, the

operating system can easily resolve which interrupt or operation will get the

highest priority. With complex systems, the priorities may need to change

dynamically. This is an easy task for an operating system to handle and is

easier to write compared to the difficulty of writing straight line code and

coping with the differ-ent pathways through the software. The end result is

easier code development, construction and maintenance.

The only interface to the operating system is in providing the message

and scheduling system. Each task can use messages or semaphores to trigger its

operation and during its processing, generate messages and toggle semaphores

which will in turn trigger other tasks. The scheduling and time sharing of the

tasks are also handled by the operating system.

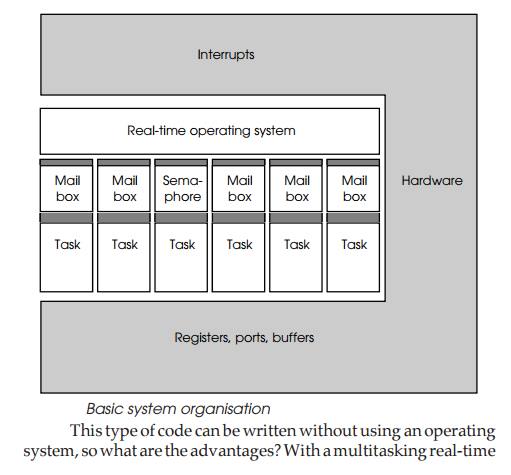

In the example shown overleaf, there are six tasks with their associated

mailboxes or semaphore. These interface to the real-time operating system which

handles message passing and sema-phore control. Interrupts are routed from the

hardware via the operating system, but the tasks can access registers, ports

and buffers directly.

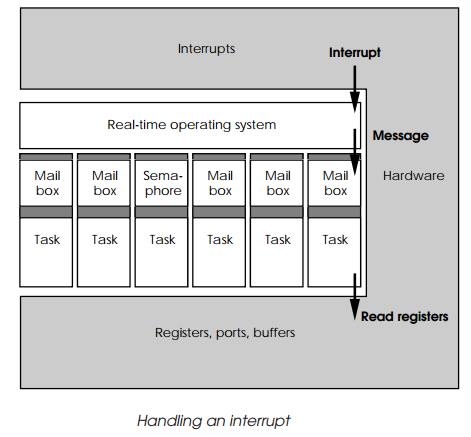

If the hardware generates an interrupt, the operating sys-tem will

service it and then send a message to the sixth task to perform some action. In

this case, it will read some registers. Once read, the task can now pass the

data on to another task for processing. This is done via the operating system.

The task sup plies the data either directly or by using a memory pointer to it

and the address of the receiving mail box. The operating system then places

this message into the mail box and the receiving task is woken up. In reality,

it is placed on the operating system scheduler ready list and allowed to

execute.

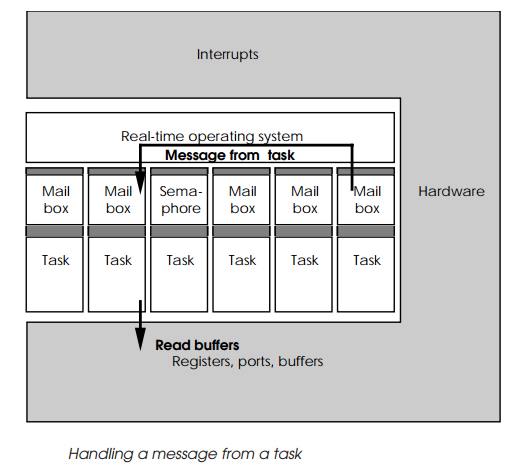

Once woken up, the receiving task can then accept the message and

process it. The message is usually designed to contain a code. This data may be

an indication of a particular function that the task is needed to perform. Using

this value, it can check to see if this function is valid given its current

state and, if so, execute it. If not, the task can return an error message back

via the operating system.

for_ever

{

Wait_for_ message(); Process message();

Discard_message();

}

Example task software loop

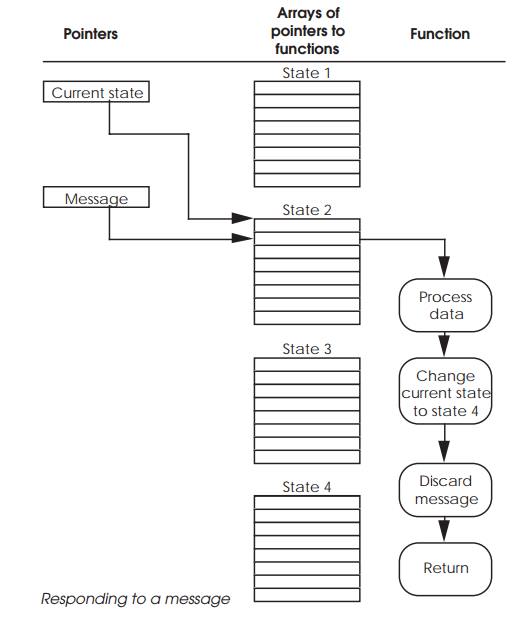

Coding this is relatively easy and can be done using a simple skeleton

program. The mechanism used to select the task’s response is via two pointers.

The first pointer reflects the current state of the task and points to an array

of functions. The second pointer is derived from the message and used to index

into the array of functions to execute the appropriate code. If the message is

irrelevant, then the selected function may do nothing. Alterna tively, it may

process information, send a message to other tasks or even change its own

current state pointer to select a different array of functions. This last

action is synonymous to changing state.

Priority levels

So far in this example, the tasks have been assumed to have equal

priority and that there is no single task that is particularly time critical

and must be completed before a particular window expires. In real applications,

this is rarely the case and certain routines or tasks are critical to meeting

the system requirements. There are two basic ways of ensuring this depending on

the facilities offered by the operating system. The first is to set the time

critical tasks and routines as the highest priority. This will nor-mally ensure

that they will complete in preference to others. However, unless the operating

system is pre-emptive and can halt the current task execution and swap it for

the time critical one, a lower priority task can still continue execution until

the end of its time slot. As a result, the time critical task may have to wait

up to a whole time slice period before it can start. In such worse cases, this

additional delay may be too long for the routine to complete in response to the

original demand or interrupt. If the triggers are asynchronous, i.e. can happen

at any time and are not particularly tied to any one event, then the lack of

pre-emption can cause a wide range of timings. Unfortunately for real-time

systems, it is the worst case that has to be assumed and used in the design.

An alternative approach offered by some operating sys-tems is the idea

of an explicit lock where the task itself issues directives to lock itself into

permanent execution. It will continue executing until it removes the lock. This

is ideal for very time critical routines where the process cannot be

interrupted by a physical interrupt or a higher priority task switch. The

disadvan-tage is that it can lead to longer responses by other tasks and in

some extreme cases system lock-ups when the task fails to remove the explicit

lock. This can be done either with the technique of special interrupt service

routines or through calls to the operating system to explicitly lock execution

and mask out any other inter-rupts. Real-time operating systems usually offer at

least one or other of these techniques.

Explicit locks

With this technique, the time critical software will make a system call

prior to execution which will tell the operating system to stop it from being

swapped out. This can also include masking out all maskable interrupts so that

only the task itself or a non-maskable interrupt can interrupt the proceedings.

The problem with this technique is that it greatly affects the performance of

other tasks within the system and if the lock is not removed can cause the task

to hog all of the processing time. In addition, it only works once the time

critical routine has been entered. If it has to wait until another task has

finished then the overall response time will be much lower.

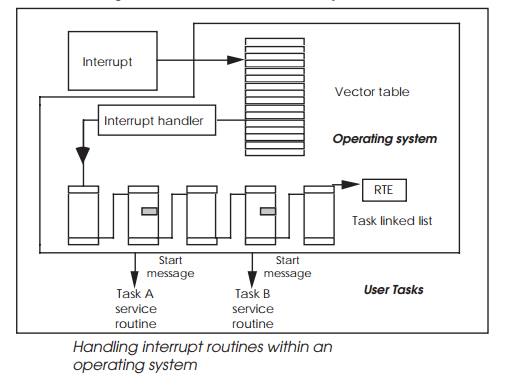

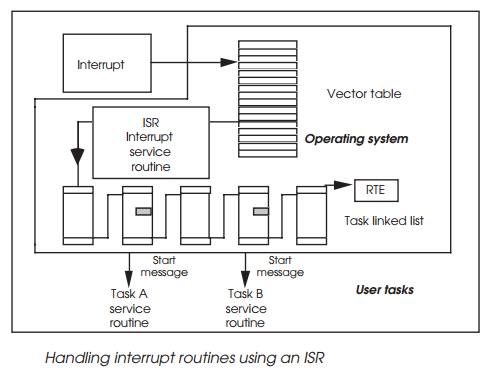

Interrupt service routines

Some operating systems, such as pSOS+, offer the facility of direct interrupt service routines or ISRs where

time critical code is executed directly. This allows critical software to

execute before other priority tasks would switch out the routines as part of a

context switch. It is effectively operating at a very low level and should not

be confused with tasks that will activate or respond to a message, semaphore or

event. In these cases, the operating system itself is working at the lower

level and effectively supplies its own ISR which in turn passes messages,

events and semaphores which activate other tasks.

The ISR can still call the operating system, but it will hold any task

switching and other activities until the ISR routine has completed. This allows

the ISR to complete without interruption.

It is possible for the ISR to send a message to its associated task to

start performing other less time critical functions associ-ated with the

interrupt. If the task was responsible for reading data from a port, the ISR

would read the data from the port and clear the interrupt and send a message to

its task to process the data further. After completing, the task would be

activated and effectively continue the processing started by the ISR. The only

difference is that the ISR is operating at the highest possible priority level

while the task can operate at whatever level the system demands.

Handling interrupt routines within an operating system

Setting priorities

Given all these different ways of synchronising and control-ling tasks,

how do you decide which ones to use and how to set them up? There is no

definitive answer to this as there are many solutions to the same problem,

depending on the detailed charac-teristics that the system needs to exhibit.

The best way to illustrate this is to take an example system and examine how it

can be implemented.

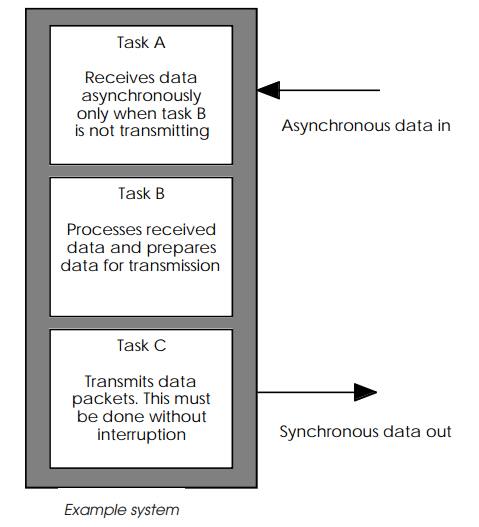

The system shown in the diagram below consists of three main tasks. Task

A receives incoming asynchronous data and passes this information onto task B

which processes it. After processing, task C takes the data and transmits it

synchronously as a packet. This operation by virtue of the processing and

syn-chronous nature cannot be interrupted. Any incoming data can fortunately be

ignored during this transmission.

Task A highest priority

In this implementation, task priorities are used with A having the

highest followed by C and finally B. The reasoning behind this is that although

task C is the most time critical, the other tasks do not need to execute while

it is running and therefore can simply wait until C has completed the

synchronous transmis-sion. When this has finished C can wake them up and make

itself dormant until it is next required. Task A with its higher priority is

then able to pre-empt B when an interrupt occurs, signalling the arrival of

some incoming data.

However, this arrangement does require some careful con-sideration. If

task A was woken up while C was transmitting data, task A would replace C by

virtue of its higher priority. This would cause problems with the synchronous

transmission. Task A could be woken up if it uses external interrupts to know

when to receive the asynchronous data. So the interrupt level used by task A

must be masked out or disabled prior to moving into a waiting mode and allowing

task C to transfer data. This also means that task A should not be allocated a

non-maskable interrupt.

Task C highest priority

An alternative organisation is to make task C the highest priority. In

this case, the higher priority level will prevent task A from gaining any

execution time and thus prevent any interrupt from interfering with the

synchronous operation. This will work fine providing that task C is forced to

be in a waiting mode until it is needed to transmit data. Once it has completed

the data transfer, it would remove itself from the ready list and wait, thus

allowing the other tasks execution time for their own work.

Using explicit locks

Task C would also be a candidate for using explicit locks to enable it

to override any priority scheme and take as much execution time as necessary to

complete the data transmission. The key to using explicit locks is to ensure

that the lock is set by all entry points and is released on all exit points. If

this is not done, the locks could be left on and thus lock out any other tasks

and cause the system to hang up or crash.

Round-robin

If a round-robin system was used, then the choice of execut-ing task

would be chosen by the tasks themselves and this would allow task C to have as

much time as it needed to transfer its data. The problem comes with deciding

how to allocate time between the other two tasks. It could be possible for task

A to receive blocks of data and then pass them onto task B for processing. This

gives a serial processing line where data arrives with task A, is proc-essed

with task B and transmitted by task C. If the nature of the data flow matches

this scenario and there is sufficient time be-tween the arrival of data packets

at task A to allow task B to process them, then there will be no problem.

However, if the arriving data is spread out, then task B’s execution may have

to be interleaved with task A and this may be difficult to schedule, and be

per-formed better by the operating system itself.

Using an ISR routine

In the scenarios considered so far, it has been assumed that task A does

not overlap with task C and they are effectively mutually exclusive. What

happens if this is not the case? It really depends on the data transfer rates

of both tasks. If they are slow, i.e. the need to send or receive a character

is slower than the context switching time, then the normal priority switching

can be used with one of the tasks allocated the highest priority. With its

synchronous communication, it is likely that it would be task C.

The mechanism would work as follows. Both tasks would be allocated their

own interrupt level with C allocated the higher priority to match that of its

higher task priority. This is important otherwise it may not get an opportunity

to respond to the interrupt routine itself. Its higher level hardware interrupt

may force the processor to respond faster but this good work could be negated

if the operating system does not allocate a time slice because an existing

higher priority task was already running.

If task A was servicing its own interrupt and a level C interrupt was

generated, task A would be pre-empted, task C would start executing and on

completion put itself back into waiting mode and thus allow task A to complete.

With a pre-emptive system, the worst case latency for task C would be the time

taken by the processor to recognise the external task C interrupt, the time

taken by the operating system to service it and finally the time taken to

perform a context switch. The worst case latency for task A is similar, but

with the addition of the worst case value for task C plus another context

switch time. The total value is the time taken by the processor to recognise

the external task A interrupt, the time taken by the operating system to

service it and, finally, the time taken to perform a context switch. The task C

latency and context switch time must be added because the task A sequence could

be interrupted and replaced at any time by task C. The extra context switch

time must be included for when task C completes and execution is switched back

to task A.

Provided these times and the time needed to execute the appropriate

response to the interrupt fit between the time critical windows, the system

will respond correctly. If not then time must be saved.

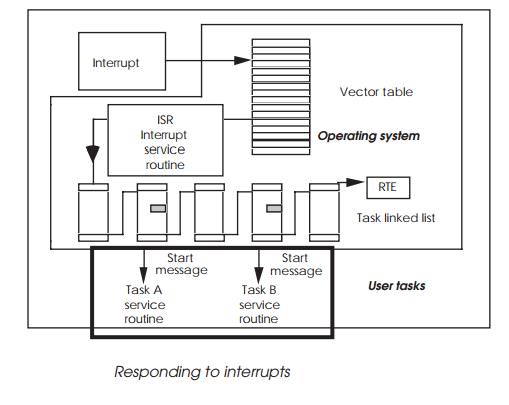

The diagram shows the mechanism that has been used so far which relies

on a message to be sent that will wake up a task. It shows that this operation

is at the end of a complex chain of events and that using an ISR, a lot of time

can be saved.

The interrupt routines of tasks A and C would be defined as ISRs. These

would not prevent context switches but will reduce the decision-making overhead

to an absolute minimum and is therefore more effective.

If the time windows still cannot be met, the only solution is to improve

the performance of the processor or use a second processor dedicated to one of

the I/O tasks.

Related Topics