Chapter: The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology: Living representatives of primitive fishes

Class Actinopterygii, Subclass Cladistia: bichirs and Reedfish - Primitive bony fishes

Class Actinopterygii, Subclass Cladistia: bichirs and Reedfish

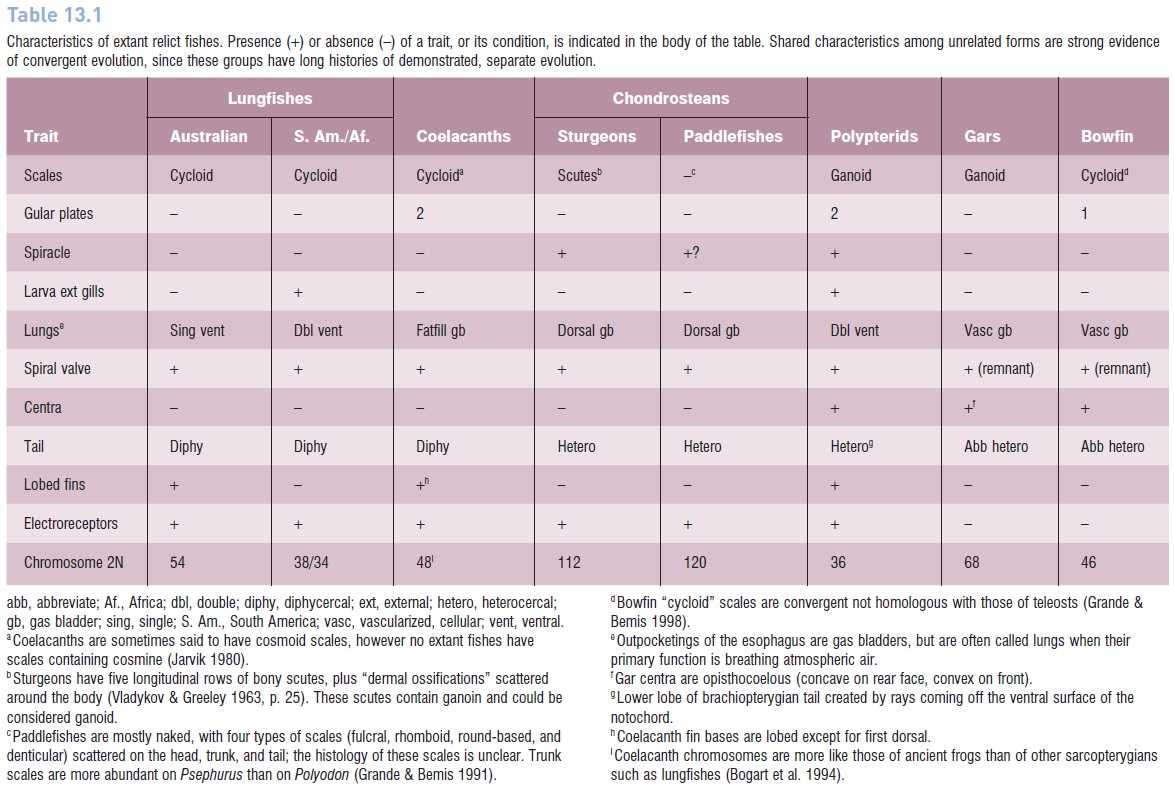

Taxonomic relationships among and within most relict groups, both in terms of affinities with other living fishes and identification of ancestral lineages, are reasonably well understood. Lungfishes, coelacanths, chondrosteans, gars, and Bowfin all have well-defined, relatively extensive fossil records with which modern species can be associated. In addition, derived traits are either unique to a group or shared with other groups in ways that confi rm evolutionary hypotheses of relationship (Table 13.1). Although healthy debate on the details of relationship among these fishes exists, most researchers agree on the general patterns of interrelatedness.

Table 13.1

Characteristics of extant relict fishes. Presence (+) or absence (–) of a trait, or its condition, is indicated in the body of the table. Shared characteristics among unrelated forms are strong evidence of convergent evolution, since these groups have long histories of demonstrated, separate evolution.

The cladistians stand out as an exception to this pattern of consensus. Over the years, workers have cited anatomical similarities to justify placing them variously with lungfishes, closer to the stemline sarcopterygians, or squarely amongst the Actinopterygii as another chondrostean (Patterson 1982). Other taxonomists emphasized unique characteristics and placed them in their own subclass, the Brachiopterygii. The fossil record was until recently uninformative, but fortunate discoveries in Middle–Upper Cretaceous deposits of southeastern Morocco establish definitive polypterid lineages at least as far back as 91– 95 mybp (Dutheil 1999). Admittedly this is still relatively recent for what is thought to be the basal actinopterygian group (i.e., chondrosteans, thought to have arisen later, have a fossil record that goes back to the Devonian;).

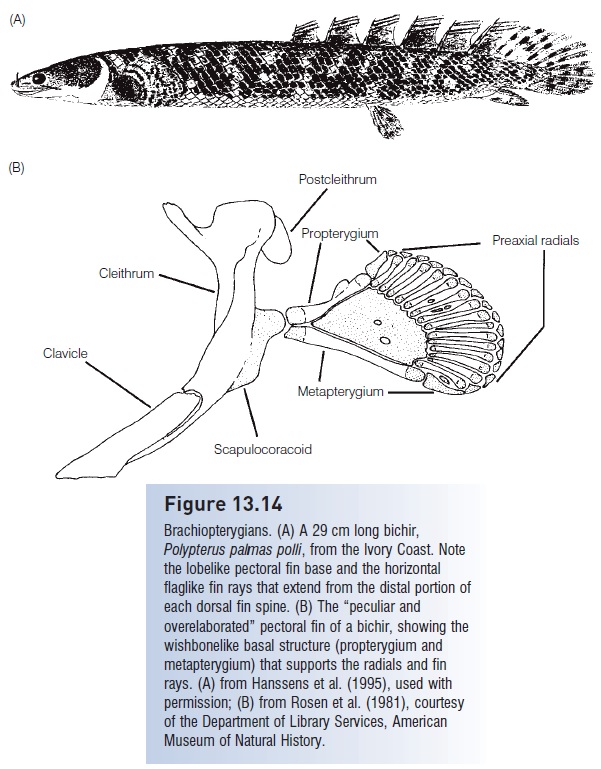

Modern cladistians are represented by two genera confined to west and central tropical Africa, including the Congo and Nile river basins (Fig. 13.14). Fifteen species, referred to as bichirs (pronounced bih-shéars), belong to the genus Polypterus; the remaining species is the Reedfish or Ropefish, Erpetoichthyes (formerly Calamoichthyes) calabaricus. Bichirs and reedfish grow to 90 cm, although most bichir species are shorter. All are predatory and inhabit shallow, vegetated, and swampy portions of lakes and rivers.

Figure 13.14

Brachiopterygians. (A) A 29 cm long bichir, Polypterus palmas polli, from the Ivory Coast. Note the lobelike pectoral fin base and the horizontal flaglike fin rays that extend from the distal portion of each dorsal fin spine. (B) The “peculiar and overelaborated” pectoral fin of a bichir, showing the wishbonelike basal structure (propterygium and metapterygium) that supports the radials and fin rays. (A) from Hanssens et al. (1995), used with permission; (B) from Rosen et al. (1981), courtesy of the Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History.

In poorly oxygenated water, bichirs are obligate air breathers and will drown if denied access to the surface. Bichirs are unique in that they use their dorsally placed spiracles to exhale (not inhale) spent air from the highly vascularized and invaginated lungs; the spiracles serve no apparent aquatic respiratory function (Abdel Magid 1966, 1967). Polypterids are additionally unique in that they inhale through their mouths by recoil aspiration (Brainerd et al. 1989). They use the elastic energy stored in their integumentary scale jacket during exhalation to power inhalation of atmospheric air. The existence of similar bony scale rows in some Paleozoic amphibians suggests that the evolution of air breathing and perhaps eventual terrestriality may be linked to recoil aspiration that originated in fishes.

Controversy over taxonomic position arises because brachiopterygians exhibit superfi cial anatomical traits that have been used to justify their inclusion in almost every one of the major taxa discussed (see Table 13.1). Cladistians possess lobelike fins (a sarcopterygian trait), ganoid scales (a palaeoniscoid or lepisosteiform trait), two gular plates (as does the coelacanth), spiracles (in common with sturgeons), feathery external gills when young and double ventral lungs (in common with lepidosirenid lungfishes), a modified heterocercal tail (as in gars and Bowfin), and a spiral valve intestine (shared by all major groups).

However, the internal structure of many of these seemingly shared primitive characteristics is very different from those of other taxa, indicating convergence on the traits and not homology. The external gills are only analogous to, not homologous with, the gills of young lungfishes. The tail is heterocercal in structure but symmetrical in external appearance; the medial and lower portions are created by rays coming off the ventral surface of the notochord, unlike any other fishes. Confusion often arises whenever we attempt to compare among living fishes, each well adapted to environmental conditions of the recent past. Many anatomical traits, in fact those most critical to systematic analyses, are retained from ancestors, whereas other traits represent recent derivations that have evolved in response to conditions greatly changed from the ancestral selection pressures. Hence we have the existence of a mosaic of primitive and derived traits in every living species, homology and analogy intertwined, with difficulty in knowing the proportions of the two. Each attempt at linking a trait in cladistians with a counterpart trait in another group becomes a possible apples-and-oranges comparison.

Related Topics