Chapter: XML and Web Services : Building XML-Based Applications : Web Services Building Blocks: SOAP(Simple Object Access Protocol)

Basic SOAP Syntax

Basic SOAP Syntax

Let’s take a closer look at the inner workings of SOAP. SOAP provides

three key capabilities:

SOAP is a messaging framework,

consisting of an outer Envelope element that contains an optional Header element and a mandatory Body element.

SOAP is an encoding format that

describes how objects are encoded, serialized, and then decoded when received.

SOAP is an RPC mechanism that

enables objects to call methods of remote objects.

It is possible to use SOAP only as a messaging framework or as a

messaging framework and an encoding format. However, the most common use of

SOAP as an encoding stan-dard is to support its use as an RPC mechanism, as

well.

SOAP Message Structure and Namespaces

Let’s start with a simple example of a message we might want to send—a

request to the server for a person’s phone number. We might have an interface

(here, written in Java) that would expose a method we might call to request the

phone number:

public interface PhoneNumber

{

public

String getPhoneNumber(String name);

}

Let’s say, then, that instead of using CORBA or RMI, our client sends an

XML-format-ted request to the server. This XML might look like the following:

<?xml version=”1.0”?> <PhoneNumber>

<getPhoneNumber>

<name>John Doe</name>

</getPhoneNumber>

</PhoneNumber>

Notice that the root node corresponds to the Java interface, and the

method as well as its parameter are nodes, too. We then use our client to

create an HTTP request, and we put the preceding XML in the body of an HTTP POST. We might expect a response from

the server that looks something like the following:

<?xml version=”1.0”?> <PhoneNumber>

<getPhoneNumberResponse>

<thenumber>

<areacode>617</areacode>

<numberbody>555-1234</numberbody>

</thenumber>

</getPhoneNumberResponse>

</PhoneNumber>

The root node retains the name of the interface, but the method name has

the word “Response” appended to it, so the client can identify the correct response by

appending “Response” to the calling method name.

In general, constructing request and response messages like the

preceding ones is a sim-ple but limited approach. The biggest limitation is

that the vocabulary that the client and server use to exchange messages must be

agreed upon beforehand. If there is a new method or a new parameter, both the

client and the server must reprogram their inter-faces. In addition, in a

complex message, there could easily be confusion if two methods have parameters

with the same name.

In order to resolve these limitations with such simple message formats,

SOAP takes advantage of XML namespaces. Let’s take a look at the same request

message recast in SOAP:

<SOAP-ENV:Envelope

xmlns:SOAP-ENV=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/”

xmlns:xsi=”http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema-instance”

xmlns:xsd=”http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema”

SOAP-ENV:encodingStyle=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/”>

<SOAP-ENV:Header> </SOAP-ENV:Header>

<SOAP-ENV:Body>

<ns:getPhoneNumber

xmlns:ns=”PhoneNumber”> <name xsi:type=”xsd:string”>John

Doe</name>

</ns:getPhoneNumber>

</SOAP-ENV:Body>

</SOAP-ENV:Envelope>

Let’s break down this request and take a closer look. First of all, its

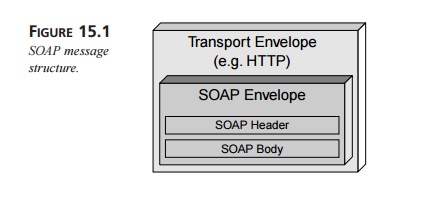

root node is Envelope, which has an optional Header section and a mandatory Body section. The SOAP Envelope is then enclosed in the outer

transport envelope, which might be HTTP, SMTP, and so on. All SOAP messages are

structured like this, as shown in Figure 15.1.

Next, notice that the message takes full advantage of namespaces.

Namespaces are a crit-ically important part of SOAP (for more about namespaces,

see Chapter 5, “The X-Files: XPath, XPointer, and XLink”). Namespaces differentiate

elements and attributes with similar names, so they can both occupy the same

document without confusion. In addi-tion, namespaces are used for versioning so

that the semantics of the XML tags can be updated or modified. Most important,

however, namespaces allow the SOAP messages to be extensible: By referencing

different namespaces, a SOAP message can extend its semantic scope (in other

words, talk about different things), and the receiver can interpret the new

message by referencing the same namespace.

You declare namespaces with the xmlns keyword. There are two forms of namespace declarations: default

declarations and explicit declarations. In our sample request, all the

declarations are explicit. Explicit declarations take the following form:

xmlns:SOAP-ENV=http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/

The default declarations look like this:

xmlns=”SomeURI”

Explicit declarations begin with the xmlns keyword, followed by a colon and a shorthand designation for the

namespace. The SOAP-ENV namespace includes the <Envelope>, <Header>, and <Body> structural elements as well as the

encodingStyle attribute, found at the URI http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/, which

is the standard URL for the SOAP-ENV namespace. An explicit declaration is used when taking advantage of a

publicly available namespace, whereas default declarations are appropriate for

custom namespaces.

In addition, the xsi

namespace maps to http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema-instance, and xsd maps to http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema. Both are also stan-dard namespaces. The xsd namespace includes the attribute string.

The Envelope element also contains the attribute:

SOAP-ENV:encodingStyle=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/”

The encodingStyle attribute informs the server receiving the message about the way that

the message content is encoded, or serialized.

The server needs this information to decode the Body element; as a result, the SOAP message is self-describing.

The encodingStyle attribute defined by http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encod-ing/

is the only one defined by the SOAP specification,

but it is not actually mandatory. An empty URI (“”) can be

used as the encoding style to disable any serialization claims from containing

elements. In addition, you can select a more restrictive serialization rule by

extending the path of the encoding style URI. In this case, the URIs indicating

the serialization rules that you want to use must be written from most specific

to least spe-cific, as follows:

SOAP-ENV:encodingStyle=”http://mysite.com/soap/encoding/restricted ➥ http://mysite.com/soap/encoding/”

Next, let’s take a look at the Body element of our SOAP request. The interface name

PhoneNumber in the line

<ns:getPhoneNumber

xmlns:ns=”PhoneNumber”>

is no longer a node name, as it was in our simplistic XML example. In

our SOAP request, PhoneNumber refers to the namespace ns. The line

<name

xsi:type=”xsd:string”>John

Doe</name>

contains the string “John Doe” as the value for the element name, which the server will understand is the parameter for the getPhoneNumber method.

Now, let’s take a look at the server’s response message:

<SOAP-ENV:Envelope

xmlns:SOAP-ENV=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/”

xmlns:xsi=”http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema-instance”

xmlns:xsd=”http://www.w3.org/1999/XMLSchema” SOAP-ENV:encodingStyle=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/encoding/”>

<SOAP-ENV:Body>

<getPhoneNumberResponse

xmlns=”SomeURI”> <areacode>617</areacode>

<numberbody>555-1234</numberbody>

</getPhoneNumberResponse>

</SOAP-ENV:Body>

</SOAP-ENV:Envelope>

The response message shows an example of a namespace with a default

declaration in the following line:

<getPhoneNumberResponse

xmlns=”SomeURI”>

In the case of a default declaration, the namespace found at SomeURI automatically scopes that

element and all its children. As a result, the <areacode> and <numberbody> elements are defined in terms of the default namespace, instead of

taking advantage of the xsi or xsd namespaces.

SOAP Envelope Element

The SOAP Envelope element is the mandatory top element of the XML document that

represents the SOAP message being sent. It may contain namespace declarations

as well as other attributes, which must be “namespace qualified.” The Envelope element may also contain

additional subelements, which must also be namespace qualified and follow the Body element.

SOAP does not define a traditional versioning model (for example, 1.0,

1.1, 2.0, and so on). Instead, SOAP handles the possibility of messages

conforming to different versions of the SOAP specification by the way it

handles the namespace associated with the

Envelope element. This namespace, http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/, is required by all SOAP messages.

If a SOAP application receives a message with a different namespace, it must

recognize this situation as a version error and discard the message. If the

underlying protocol requires a response (as with HTTP), the SOAP application

must respond with a VersionMismatch faultcode using the http:// schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/

namespace. (More about faultcodes later in the chapter.)

SOAP Header Element

The SOAP Header element is optional and is used for extending messages without any sort

of prior agreement between the two communicating parties. You might use the Header element for authentication,

transaction support, payment information, or other capabilities that the SOAP

specification doesn’t provide.

Let’s take a look at a typical Header element:

<SOAP-ENV:Header>

<t:Transaction xmlns:t=“myURI”

SOAP-ENV:mustUnderstand=“1”>

3

</t:Transaction> </SOAP-ENV:Header>

The Header element is the first immediate child of the Envelope element, and child ele-ments of

the Header element

are called header entries. In this

example, the header entry is the Transaction element. Header entries must be identified by their fully qualified

element names (in this case, xmlns:t=”myURI”, where the namespace URI is represented by myURI, and the local name is t).

The SOAP Header element may also optionally contain the following attributes:

A SOAP encodingStyle attribute, which would indicate

the serialization rules for the header entries.

A SOAP mustUnderstand attribute (as in our example),

which indicates whether it is optional or mandatory to process the header

entry. This attribute is explained in this section.

A SOAP actor attribute, which indicates who

is supposed to process the header entry and how they are supposed to process

it. The actor attribute is also explained in more detail in this section.

The value of the mustUnderstand attribute is either 1,

indicating that the recipient must process the header entry, or 0, indicating that the header

entry is optional. If this attribute doesn’t appear, processing the header

entry is assumed to be optional provide.

If the attribute is set to 1, the recipient must either process the semantics of the header entry

properly according to its URI or fail processing the message and return an

error. Therefore, if there is a change in the semantics associated with a

header entry, setting the mustUnderstand attribute to 1

guarantees that the recipient will process the new semantics.

In the preceding example, the Transaction element is mandatory, as indicated by the mustUnderstand attribute, and has a value of 3, indicating which transaction

the current message

belongs to.

The second optional header entry attribute is the actor attribute. The SOAP actor attribute indicates the

recipient of the header entry. If there are only two parties involved in a

message (namely, the sender and the recipient), the actor attribute is extraneous.

However, in many cases, intermediaries will process a SOAP message on its way

from the sender to the recipient. These intermediaries are typically interested

in only part of the SOAP message. For example, a firewall may check the Envelope element for allowed URIs but may

not be interested in the Body element.

If an intermediary receives a SOAP message and determines that part of

the message is for itself, it must remove that part of the message before

sending on the rest. Of course, the intermediary may also add to the message,

as well. The actor attribute might be used to indicate that part of the message is

intended for a particular intermediary or possibly for the final recipient.

There is also a special URI:

http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/actor/next

This URI can be used as the value for the actor attribute that indicates that the header entry is intended for the next

application down the line to process the message provide.

SOAP Body Element

The mandatory Body element is an immediate child of the Envelope element and must immediately follow the Header element if a header is present. Each immediate child of the Body element is called a body entry. The Body element is used to carry the

payload of the SOAP message, and there is a great deal of latitude in what you

can place in the Body element. Body entries are identified by their fully qualified element names.

Typically, the SOAP encodingStyle attribute is used to indicate the serialization rules for body

enti-ties, but this encoding style is not required.

The only Body entry explicitly defined in the SOAP specification is the Fault entry, used for reporting

errors. The Fault entry is explained later in the chapter.

Data Types

The SOAP specification allows for the use of custom encodings, but

typically you are likely to use the default encoding defined in http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/ encoding/. If you use this encoding, you

get to take advantage of its data model, which is structured to be consistent with the data models of today’s popular

programming languages, including Java, Visual Basic, and C++.

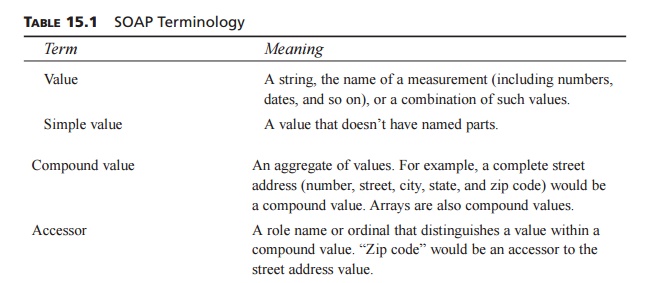

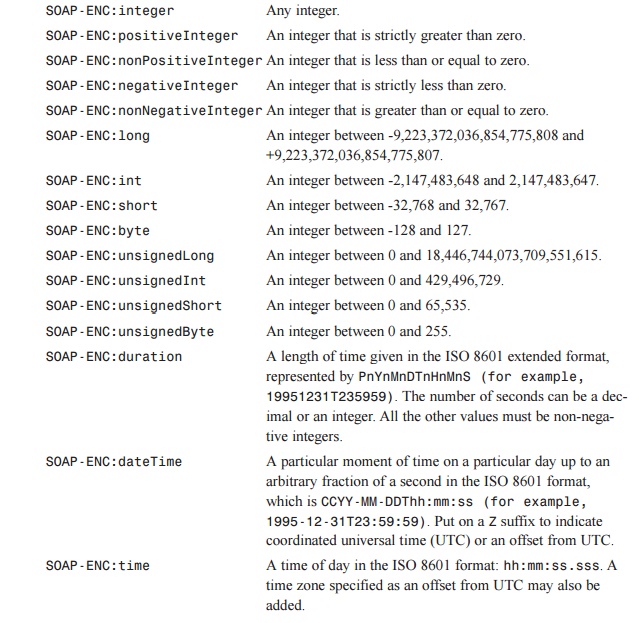

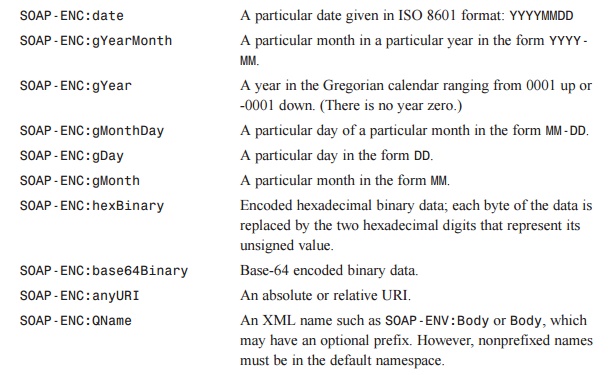

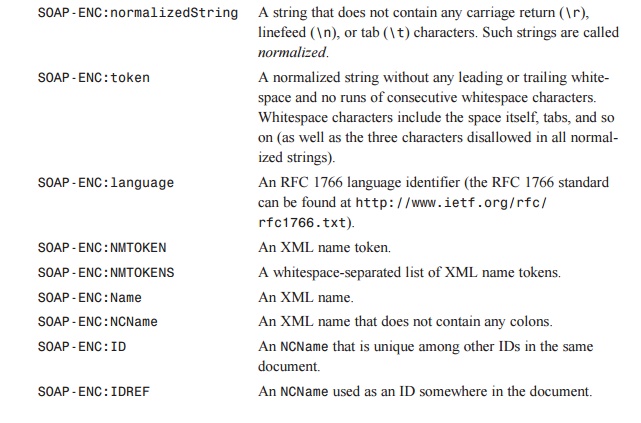

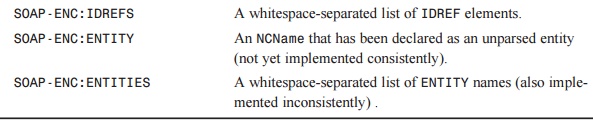

First of all, the standard encoding provides for the terminology defined

in Table 15.1.

TABLE 15.1 SOAP Terminology

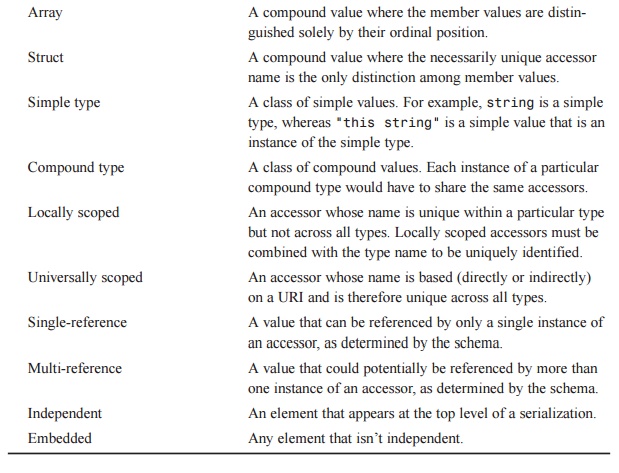

Next, the standard encoding provides for SOAP’s

simple types, which are based on the “Primitive Datatypes” section of the XML

Schema specification. SOAP’s primitive data types are described in Table 15.2.

TABLE 15.2 SOAP Primitive Data Types

These data types can be used directly in SOAP elements:

<SOAP-ENC:int>47</SOAP-ENC:int>

In addition, the data types support the id and href attributes, allowing multiple refer-ences to the same value:

<SOAP-ENC:string id=“mystr”>The string</SOAP-ENC:string>

<SOAP-ENC:string href=“#mystr”/>

Furthermore, if the attributes are defined within a schema, you might

have the following example:

<bodystring id=“mystr”>The string</bodystring> <newstring

href=”#newstring”/>

In this case, the schema would include the following fragments:

<element name=”bodystring” type=”SOAP-ENC:string”> <element

name=”newstring” type=”SOAP-ENC:string”>

The only difference between this approach and declaring an element to be

of type

“xsd:string” is that “SOAP-ENC:string” allows for the id and href attributes.

Arrays

Arrays are examples of compound values, where the member values in an

array are dis-tinguished only by their ordinal value. Arrays can contain

elements that are of any type, including nested arrays. Here is an example of

an array containing integers:

<SOAP-ENC:Array

SOAP-ENC:arrayType=”xsd:int[2]”> <SOAP-ENC:int>4</SOAP-ENC:int>

<SOAP-ENC:int>33</SOAP-ENC:int>

</SOAP-ENC:Array>

Alternately, the same array can be represented with the use of the

schema, as follows:

<myIntegers SOAP-ENC:arrayType=”xsd:int[2]”>

<num>4</num>

<num>33</num>

</myIntegers>

Here’s the corresponding schema fragment:

<element

name=”myIntegers”

type=”SOAP-ENC:Array”>

A third way of specifying types of member elements is with the xsi:type attribute in the instance, as

shown here:

<SOAP-ENC:Array SOAP-ENC:arrayType=”xsd:ur-type[3]”>

<item xsi:type=”xsd:int”>4</item>

<item

xsi:type=”xsd:decimal”>3.456</item>

<item xsi:type=”xsd:string”>This is a

string</item> </SOAP-ENC:Array>

This example also shows how the types of the member elements of an array

can vary.

It is also possible for arrays to be multidimensional. Here is an

example of a two-dimen-sional array:

<myStrings

SOAP-ENC:arrayType=”xsd:string[2,3]”> <str>Row 1 Column 1</str>

<str>Row 1 Column 2</str>

<str>Row 1 Column 3</str> <str>Row 2 Column 1</str>

<str>Row 2 Column 2</str> <str>Row 2 Column 3</str>

</myStrings>

Arrays may also have other arrays or other compound values as member

elements.

Finally, the SOAP specification defines two additional types of arrays:

partially transmit-ted or varying arrays and sparse arrays. A partially

transmitted array is an array that only has some of its elements specified. The

“SOAP-ENC:offset”

attribute indicates when the first specified element isn’t the array’s first

element, as shown in the following example:

<SOAP-ENC:Array

Type=”xsd:string[5]” SOAP-ENC:offset=”[2]”> <str>The third element of

the Array</str>

<str>The fourth element of the

Array</str> </SOAP-ENC:Array>

SOAP handles sparse arrays by defining a SOAP-ENC:position attribute that indicates a member value’s position within an array, as

shown in the following example:

<SOAP-ENC:Array

Type=”xsd:string[5,5]”>

<str SOAP-ENC:position=”[1,2]”>Second row,

third column</str> <str SOAP-ENC:position=”[4,0]”>Fifth row, first

column</str>

</SOAP-ENC:Array>

Structs

In addition to arrays, structs are also examples of compound values,

where the member values in a struct are identified by unique accessor names. A

simple example of a struct is given here:

<elt:Purchase>

<buyer>John Doe</buyer> <item>Widget</item>

<count>2</count> <cost>14.47</cost>

</elt:Purchase>

The following schema fragment describes the struct:

<element name=”Purchase”>

<complexType>

<element name=”buyer” type=”xsd:string”/>

<element name=”item” type=”xsd:string”/> <element name=”count”

type=”xsd:int”/> <element name=”cost” type=”xsd:decimal”/>

</complexType>

</element>

With structs, the name of the element is unique and identifies the

element. The order of elements is irrelevant.

We can expand the preceding struct by giving the buyer element some child elements of

its own:

<elt:Purchase>

<buyer>

<name>John Doe</name> <address>1

Web St.</address>

</buyer>

<item>Widget</item>

<count>2</count>

<cost>14.47</cost>

</elt:Purchase>

This is the best way of handling nested elements when they are

single-reference. However, if the buyer element were multi-reference, which would be true in the case of a

purchase (because John Doe would hopefully be expected to make additional

pur-chases), then the following struct would be more appropriate:

<elt:Purchase>

<buyer href=”#Person-1”/>

<item>Widget</item> <count>2</count>

<cost>14.47</cost>

</elt:Purchase> <elt:Person id=”Person-1”>

<name>John Doe</name> <address>1

Web St.</address>

</elt:Person>

In this example, “John Doe” is an example of an independent element,

which represents an instance of a type (in this case, Person) that is referred to by at least

one multi-refer-ence accessor (in this case, buyer). Such independent elements must be tagged with the id attribute and must be unique

within the SOAP message.

Both of the two struct examples would be described by the following

schema fragment:

<element name=”Purchase”

type=”tns:Purchase”> <complexType name=”Purchase”>

<sequence minOccurs=”0”

maxOccurs=”1”> <element name=”buyer” type=”tns:Person”/>

<element name=”item”

type=”xsd:string”/> <element name=”count” type=”xsd:int”/>

<element name=”cost”

type=”xsd:decimal”/>

</sequence>

<attribute name=”href” type=”uriReference”/>

<attribute name=”id” type=”ID”/>

<anyAttribute namespace=”##other”/>

</complexType>

</element>

<element name=”Person”

base=”tns:Person”> <complexType name=”Person”>

<element name=”name” type=”xsd:string”/>

<element name=”address” type=”xsd:string”/>

</complexType>

</element>

Note that the child elements of the sequence element might occur at most once, in which case the href attribute would not occur.

The preceding examples cover the breadth of what can be done with

structs, but there are many different ways of building them. For example, it is

also possible to nest multi-reference elements, for example, if a Person element might have more than one

address element.

In addition, elements can themselves be compound values.

Faults

The SOAP Fault element carries error messages (typically in response messages) or

other status information. This element is optional, but if it is present, it

must appear only once as a body entry.

Here is an example of a SOAP response message with a Fault element:

<SOAP-ENV:Envelope

xmlns:SOAP-ENV=”http://schemas.xmlsoap.org/soap/envelope/”>

<SOAP-ENV:Body>

<SOAP-ENV:Fault>

<faultcode>SOAP-ENV:Server</faultcode> <faultstring>Unable to

process message</faultstring> <detail>

<dtl:faultDetail

xmlns:dtl=”Some-URI”> <message>Namespace mismatch</message>

<errorcode>47</errorcode>

</dtl:faultDetail>

</detail>

</SOAP-ENV:Fault>

</SOAP-ENV:Body> </SOAP-ENV:Envelope>

First, notice that the Fault element has three child elements. There are a total of four possible

subelements to the Fault element:

The faultcode element is mandatory and

provides a mechanism for software applications to find the fault. SOAP defines

four faultcodes (provided in the fol-lowing list).

The faultstring element is also mandatory and

provides a human-readable expla-nation of the fault.

The faultactor element is optional and is used

when there are intermediaries in the message path. It parallels the SOAP actor attribute (described earlier),

provid-ing a URI that indicates the source of the fault.

The detail element carries error

information related specifically to the Body ele-

ment and is mandatory if the message recipient

could not process the Body element of the original message. (Error information about header

entries must be carried within the Header element.) If the detail element is missing, the recipient of the fault message knows that the

fault occurred before the Body element was processed.

• Other

namespace-qualified Fault elements are also allowed.

As mentioned in the preceding list, SOAP provides for four faultcodes:

A VersionMismatch faultcode indicates that the recipient found an invalid name-space for

the SOAP Envelope element.

The MustUnderstand faultcode indicates that a SOAP

header entry with a MustUnderstand attribute set to “1” was not understood (or not obeyed).

The Client faultcode indicates a problem

with the request message itself. The problem might be malformed XML or missing

information that is required by the recipient.

The Server class of faultcodes indicates

that the recipient was unable to process the message, but the problem was not

directly caused by the request message. A typical Server faultcode would result from the

server application failing to obtain required data from another system. The

server may send a subsequent successful response if the problem is resolved.

Related Topics