Chapter: Organic Chemistry: Acid–base reactions

Base strength

BASE STRENGTH

Key Notes

Electronegativity

The

basicity of negatively charged compounds depends on the electroneg- ativity of

the atoms bearing the negative charge. The more electronegative the atom, the

less basic the compound will be, due to stabilization of the charge by the

electronegative atom. Therefore, carbanions are more basic than nitrogen

anions. Nitrogen anions are more basic than oxygen anions.

Oxygen

anions are more basic than halides. The basicity of neutral mole- cules can

be explained by

comparing the stability

of their positively charged conjugate acids. Amines

are more basic than alcohols since nitro- gen is less electronegative than

oxygen and more capable of stabilizing a positive charge. Alkyl halides are

extremely weak bases because the result- ing

cations are poorly

stabilized by a

strongly electronegative halogen atom.

pKb

pKb is a measure of basic strength. The lower the

value of pKb the stronger the base. pKa

and pKb are related by the equation pKa + pKb = 14. Therefore, a knowledge of the pKa value

for an acid allows the pKb of its conjugate base to be calculated

and vice versa.

Inductive effects

Inductive

effects affect the stability of the negative charge on charged bases.

Electron-withdrawing groups diminish the charge and stabilize the base, making

it less reactive and a weaker base. Electron-donating groups will increase the

charge and destabilize the base, making it a stronger base. Inductive effects

also affect the strength of neutral bases by stabilizing or destabilizing the

positive charge on the conjugate acid. Electron-donating groups stabilize the

positive charge and stabilize the conjugate acid which means that it will be

formed more easily and the original base will be a strong base.

Electron-withdrawing groups will have the opposite effect.

Solvation effects

Solvation

affects basic strength. Water solvates alkyl ammonium ions by forming hydrogen

bonds to N–H protons. The greater the number of N–H protons, the

greater the solvation and the greater the stabilizing effect on the alkyl

ammonium ion. The solvation effect is greater for alkyl ammo-nium ions formed

from primary amines than it is for alkyl ammonium ions formed from secondary

and tertiary amines. Therefore, primary amines should be stronger bases than

secondary or tertiary amines. How-ever, the inductive effect of alkyl groups is

greater for tertiary amines than it is for primary and secondary amines.

Therefore, it is not possible to predict the relative order of basicity for

primary, secondary and tertiary amines.

Resonance

Resonance

can stabilize a negative charge by delocalizing it over two or more atoms.

Stabilization of the charge means that the ion is less reactive and is a weaker

base. Carboxylate ions are weaker bases than phenolate ions, and phenolate ions

are weaker bases than alkoxide ions. Aromatic amines are weaker bases than

alkylamines since the lone pair of electrons on an aromatic amine interacts

with the aromatic ring through resonance and is less available for bonding to a

proton.

Amines and amides

Amines

are weak bases. They have a lone pair of electrons which can bind to a proton

and are in equilibrium with their conjugate acid in aqueous solution. Amides

are not basic because the lone pair of electrons on the nitrogen is involved in

a resonance mechanism which involves the neighboring carbonyl group.

Electronegativity

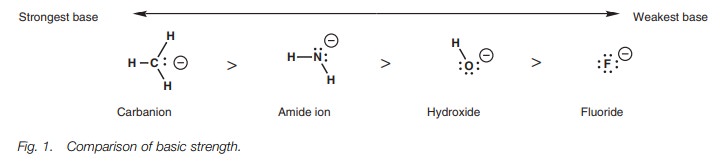

Electronegativity has an important influence to

play on basic strength. If we compare the fluoride ion, hydroxide ion, amide

ion and the methyl carbanion, then the order of basicity is as shown (Fig. 1).

The strongest base is the carbanion since this

has the negative charge situ-ated on the least electronegative atom – the

carbon atom. The weakest base is the fluoride ion which has the negative charge

situated on the most electro-negative atom – the fluorine atom. Strongly

electronegative atoms such as flu-orine are able to stabilize a negative charge

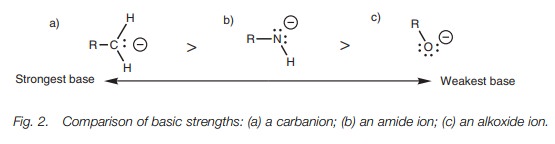

making the ion less reactive and less basic. The order of basicity of the

anions formed from alkanes, amines, and alcohols follows a similar order for

the same reason (Fig. 2).

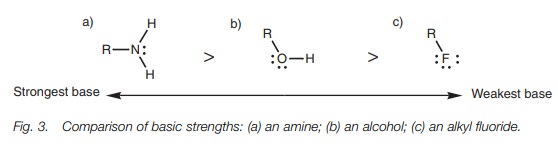

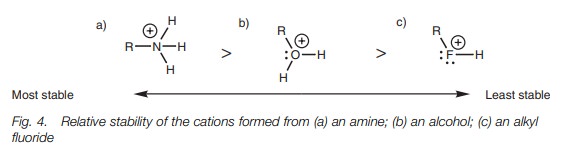

Electronegativity also explains the order of

basicity for neutral molecules such as amines, alcohols, and alkyl halides (Fig. 3).

These neutral molecules are much weaker bases than their corresponding anions, but the order of basicity is still the same and can be explained by considering the relative stability of the cations which are formed when these molecules bind a proton (Fig. 4).

A nitrogen atom can stabilize a positive charge

better than a fluorine atom since the former is less electronegative.

Electronegative atoms prefer to have a negative charge rather than a positive

charge. Fluorine is so electronegative that its basicity is negligible.

Therefore, amines act as weak bases in aqueous solution and are par-tially

ionized. Alcohols only act as weak bases in acidic solution. Alkyl halides are

essentially nonbasic even in acidic solutions.

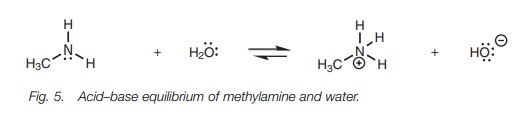

pKb

pKb is

a measure of

basic strength. If

methylamine is dissolved

in water, an equilibrium is set up (Fig. 5).

Methylamine on the left hand side of the

equation is termed the free base,

while the methyl ammonium ion formed on the right hand side is termed the conjugateacid. The extent of ionization

or dissociation in the equilibrium reaction is definedby the equilibrium constant (Keq);

Keqis

normally measured in a dilute aqueous solution of the base and so

theconcentration of water is high and assumed to be constant. Therefore, we can

rewrite the equilibrium equation in a simpler form where Kb is the basicity con-stant and includes the

concentration of pure water (55.5 M). pKb

is the negative logarithm of Kb

and is used as a measure of basic strength (pKb = - Log10Kb).

A large pKb

indicates a weak base. For example, the pKb

values of ammonia and methylamine are 4.74 and 3.36, respectively, which

indicates that ammonia is a weaker base than methylamine.

pKb

and pKa are related by the

equation pKa + pKb = 14. Therefore, if one

knows the pKa of an acid,

the pKb of the conjugate

base can be calculated and vice versa.

Inductive effects

Inductive effects affect the strength of a

charged base by influencing the negative charge. For example, an

electron-withdrawing group helps to stabilize a negative charge, resulting in a

weaker base. An electron-donating group will destabilize a negative charge

resulting in a stronger base. We discussed this when we compared the relative

acidities of the chlorinated ethanoic acids Cl3CCO2H, Cl2CHCO2H,

ClCH2CO2H, and CH3CO2H.

Trichloroacetic acid is a strong acid because its conjugate base (the

carboxylate ion) is stabilized by the three electronegative chlorine groups (Fig. 6).

The chlorine atoms have an electron-withdrawing

effect on the negative charge which helps to stabilize it. If the negative

charge is stabilized, it makes the conju-gate base less reactive and a weaker

base. Note that the conjugate base of a strong acid is weak, while the

conjugate base of a weak acid is strong. Therefore, the order of basicity for

the ethanoate ions Cl3CCO2-, Cl2CHCO2-,

ClCH2CO2-, and CH3CO2-

is the opposite to the order of acidity for the corresponding carboxylic

acids, that is, the ethanoate ion is the strongest base, while the

trichlorinated ethanoate ion is the weakest base.

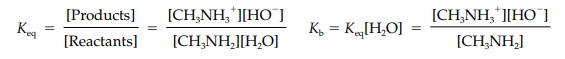

Inductive effects also influence the basic

strength of neutral molecules (e.g. amines). The pKb for ammonia is 4.74, which compares with pKb values for methylamine,

ethylamine, and propylamine of 3.36, 3.25 and 3.33 respectively. The

alkylamines are stronger bases than ammonia because of the inductive effect of

an alkyl group on the alkyl ammonium ion

(RNH3+;Fig. 7).

Alkyl groups donate electrons towards a neighboring positive center and this

helps to stabilize the ion since some of the positive charge is partially

dispersed over the alkyl group. If the ion is stabilized, the equilibrium of

the acid–base reaction will shift to the ion, which means that the amine is

more basic. The larger the alkyl group, the more significant this effect.

If one alkyl group can influence the basicity of an amine, then further alkyl groups should have an even greater inductive effect. Therefore, one might expect secondary and tertiary amines to be stronger bases than primary amines. In fact, this is not necessarily the case. There is no easy relationship between basicity and the number of alkyl groups attached to nitrogen. Although the inductive effect of more alkyl groups is certainly greater, this effect is counterbalanced by a solvation effect.

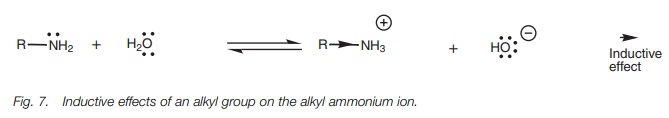

Solvation effects

Once the alkyl ammonium ion is formed, it is

solvated by water molecules – a process which involves hydrogen bonding between

the oxygen atom of water and any N–H group present in the alkyl ammonium

ion (Fig. 8). Water solvation is a

stabilizing factor which is as important as the inductive effect of alkyl

substituents and the more hydrogen bonds which are possible, the greater the

stabilization. Solvation is stronger for the alkyl ammonium ion formed from a

primary amine than for the alkyl ammonium ion formed from a tertiary amine.

This is because the former ion has three N–H hydrogens available for

H-bonding, compared with only one such N–H hydrogen for the latter. As a

result, there is more solvent stabilization experienced for the alkyl ammonium

ion of a primary amine compared to that experienced by the alkyl ammonium ion

of a tertiary amine. This means that tertiary amines are generally weaker bases

than primary or secondary amines.

Resonance

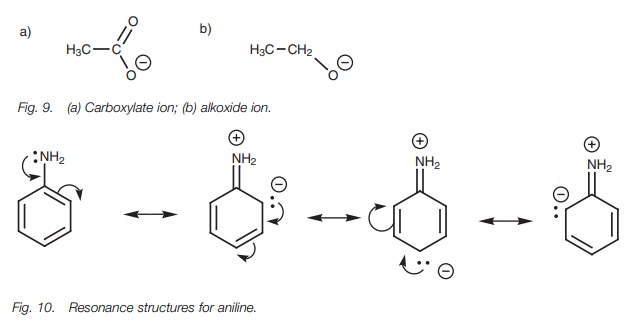

We have already discussed how resonance can

stabilize a negative charge by delocalizing it over two or more atoms. This

explains why a carboxylate ion is more stable than an alkoxide ion. The

negative charge in the former can be delocalized between two oxygens whereas

the negative charge on the former is localized on the oxygen. We used this

argument to explain why a carboxylic acid is a stronger acid than an alcohol.

We can use the same argument in reverse to explain the difference in basicities

between a carboxylate ion and an alkoxide ion (Fig. 9). Since the latter is less stable, it is more reactive and

is therefore a stronger base.

Resonance effects also explain why aromatic amines (arylamines) are weaker bases than alkylamines. The lone pair of electrons on nitrogen can interact with the π system of the aromatic ring, resulting in the possibility of three zwitterionic resonance structures (Fig. 10). (A zwitterion is a neutral molecule containing a pos-itive and a negative charge.) Since nitrogen’s lone pair of electrons is involved in this interaction, it is less available to form a bond to a proton and so the amine is less basic.

Amines and amides

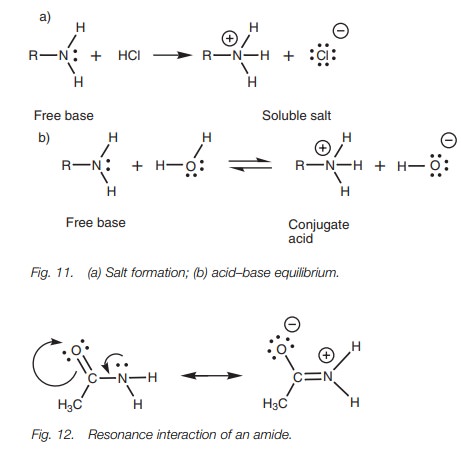

Amines are weak bases. They form water soluble

salts in acidic solutions (Fig. 11a),

and in aqueous solution they are in equilibrium with their conjugate acid(Fig. 11b).

Amines are basic because they have a lone pair

of electrons which can form a bond to a proton. Amides also have a nitrogen with

a lone pair of electrons, but unlike amines they are not basic. This is because

a resonance takes place within the amide structure which involves the nitrogen

lone pair (Fig. 12). The driving

force behind this resonance is the electronegative oxygen of the neighboring

car-bonyl group which is ‘hungry’ for electrons. The lone pair of electrons on

nitrogen forms a π bond to the neighboring carbon atom. As this

takes place, the π bond of the carbonyl group breaks and both

electrons move onto the oxygen to give it a total of three lone pairs and a

negative charge. Since the nitrogen’s lone pair is involved in this resonance,

it is unavailable to bind to a proton and therefore amides are not basic.

Related Topics