Chapter: social science geography student essay writing

Are the Increases in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide and Other Greenhouse Gases During the Industrial Era Caused by Human Activities?

Are the Increases in

Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide and Other Greenhouse Gases During the Industrial Era

Caused by Human Activities?

Yes, the increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) and

other greenhouse gases during the industrial era are caused by human

activities. In fact, the observed increase in atmospheric CO2 concentrations

does not reveal the full extent of human emissions in that it accounts for only

55% of the CO2 released by human activity since 1959. The rest has been taken

up by plants on land and by the oceans. In all cases, atmospheric

concentrations of greenhouse gases, and their increases, are determined by the

balance between sources (emissions of the gas from human activities and natural

systems) and sinks (the removal of the gas from the atmosphere by conversion to

a different chemical compound). Fossil fuel combustion (plus a smaller

contribution from cement manufacture) is responsible for more than 75% of

human-caused CO2 emissions. Land use change (primarily deforestation) is

responsible for the remainder. For methane, another important greenhouse gas,

emissions generated by human activities exceeded natural emissions over the

last 25 years. For nitrous oxide, emissions generated by human activities are

equal to natural emissions to the atmosphere. Most of the long-lived

halogen-containing gases (such as chlorofluorcarbons) are manufactured by

humans, and were not present in the atmosphere before the industrial era. On

average, present-day tropospheric ozone has increased 38% since pre-industrial

times, and the increase results from atmospheric reactions of short-lived

pollutants emitted by human activity. The concentration of CO2 is now 379 parts

per million (ppm) and methane is greater than 1,774 parts per billion (ppb),

both very likely much higher than any time in at least 650 kyr (during which

CO2 remained between 180 and 300 ppm and methane between 320 and 790 ppb). The

recent rate of change is dramatic and unprecedented; increases in CO2 never

exceeded 30 ppm in 1 kyr - yet now CO2 has risen by 30 ppm in just the last 17

years.

Carbon Dioxide

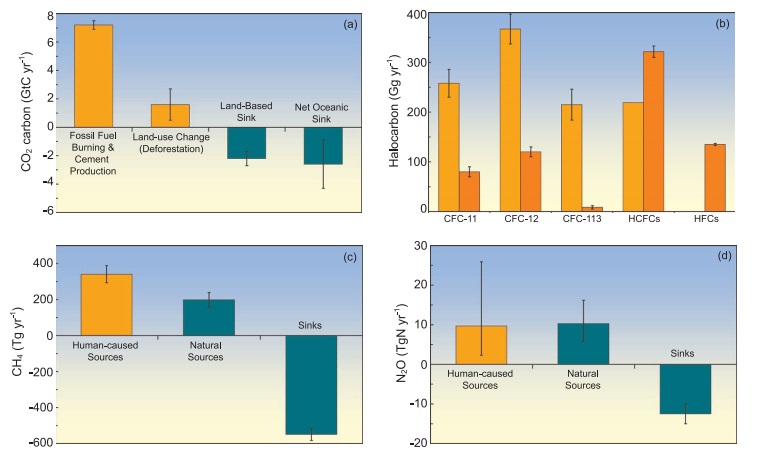

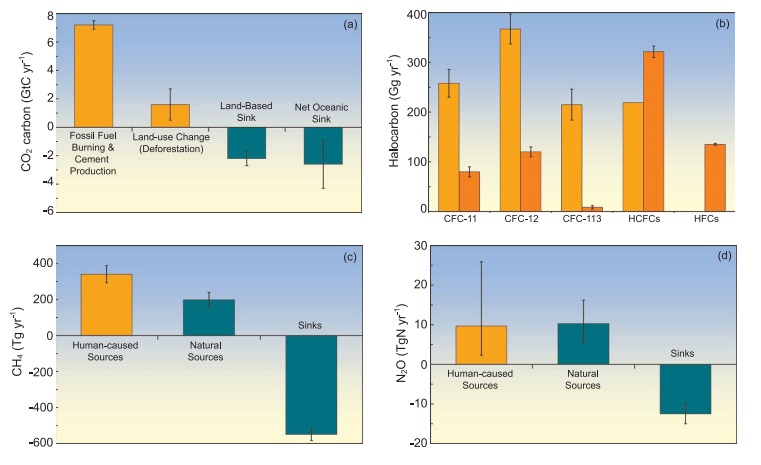

Emissions of CO2 (Figure 1a) from fossil fuel combustion,

with contributions from cement manufacture, are responsible for more than 75%

of the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration since pre-industrial times.

The remainder of the increase comes from land use changes dominated by

deforestation (and associated biomass burning) with contributions from changing

agricultural practices. All these increases are caused by human activity. The

natural carbon cycle cannot explain the observed atmospheric increase of 3.2 to

4.1 GtC yr-1 in the form of CO2 over the last 25 years. (One GtC equals 1015

grams of carbon, i.e., one billion tonnes.)

Natural processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, decay

and sea surface gas exchange lead to massive exchanges, sources and sinks of

CO2 between the land and atmosphere (estimated at ~120 GtC yr-1) and the ocean

and atmosphere (estimated at ~90 GtC yr-1; see figure 7.3). The natural sinks

of carbon produce a small net uptake of CO2 of approximately 3.3 GtC yr-1 over

the last 15 years, partially offsetting the human-caused emissions. Were it not

for the natural sinks taking up nearly half the human-produced CO2 over the

past 15 years, atmospheric concentrations would have grown even more

dramatically.

The increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration is known to be

caused by human activities because the character of CO2 in the atmosphere, in

particular the ratio of its heavy to light carbon atoms, has changed in a way

that can be attributed to addition of fossil fuel carbon. In addition, the

ratio of oxygen to nitrogen in the atmosphere has declined as CO2 has

increased; this is as expected because oxygen is depleted when fossil fuels are

burned. A heavy form of carbon, the carbon-13 isotope, is less abundant in

vegetation and in fossil fuels that were formed from past vegetation, and is

more abundant in carbon in the oceans and in volcanic or geothermal emissions.

The relative amount of the carbon-13 isotope in the atmosphere has been

declining, showing that the added carbon comes from fossil fuels and

vegetation. Carbon also has a rare radioactive isotope, carbon-14, which is

present in atmospheric CO2 but absent in fossil fuels. Prior to atmospheric

testing of nuclear weapons, decreases in the relative amount of carbon-14

showed that fossil fuel carbon was being added to the atmosphere.

Halogen-Containing

Gases

Human activities are responsible for the bulk of long-lived

atmospheric halogen-containing gas concentrations. Before industrialisation,

there were only a few naturally occurring halogencontaining gases, for example,

methyl bromide and methyl chloride. The development of new techniques for

chemical synthesis resulted in a proliferation of chemically manufactured

halogen-containing gases during the last 50 years of the 20th century.

Emissions of key halogen-containing gases produced by humans are shown in

Figure 1b. Atmospheric lifetimes range from 45 to 100 years for the

chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) plotted here, from 1 to 18 years for the

hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and from 1 to 270 years for the

hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). The perfluorocarbons (PFCs, not plotted) persist in

the atmosphere for thousands of years. Concentrations of several important

halogen-containing gases, including CFCs, are now stabilising or decreasing at

the Earth's surface as a result of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that

Deplete the Ozone Layer and its Amendments. Concentrations of HCFCs, production

of which is to be phased out by 2030, and of the Kyoto Protocol gases HFCs and

PFCs, are currently increasing.

Methane Methane (CH4)

Methane Methane (CH4) sources

to the atmosphere generated by human activities exceed CH4 sources from natural

systems (Figure 1c). Between 1960 and 1999, CH4 concentrations grew an average

of at least six times faster than over any 40-year period of the two millennia

before 1800, despite a near-zero growth rate since 1980. The main natural

source of CH4 to the atmosphere is wetlands. Additional natural sources include

termites, oceans, vegetation and CH4 hydrates. The human activities that

produce CH4 include energy production from coal and natural gas, waste disposal

in landfills, raising ruminant animals (e.g., cattle and sheep), rice

agriculture and biomass burning. Once emitted, CH4 remains in the atmosphere

for approximately 8.4 years before removal, mainly by chemical oxidation in the

troposphere. Minor sinks for CH4 include uptake by soils and eventual

destruction in the stratosphere.

Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous oxide (N2O) sources to the atmosphere from human

activities are approximately equal to N2O sources from natural systems (Figure

1d). Between 1960 and 1999, N2O concentrations grew an average of at least two

times faster than over any 40-year period of the two millennia before 1800.

Natural sources of N2O include oceans, chemical oxidation of ammonia in the

atmosphere, and soils. Tropical soils are a particularly important source of

N2O to the atmosphere. Human activities that emit N2O include transformation of

fertilizer nitrogen into N2O and its subsequent emission from agricultural

soils, biomass burning, raising cattle and some industrial activities,

including nylon manufacture. Once emitted, N2O remains in the atmosphere for

approximately 114 years before removal, mainly by destruction in the

stratosphere.

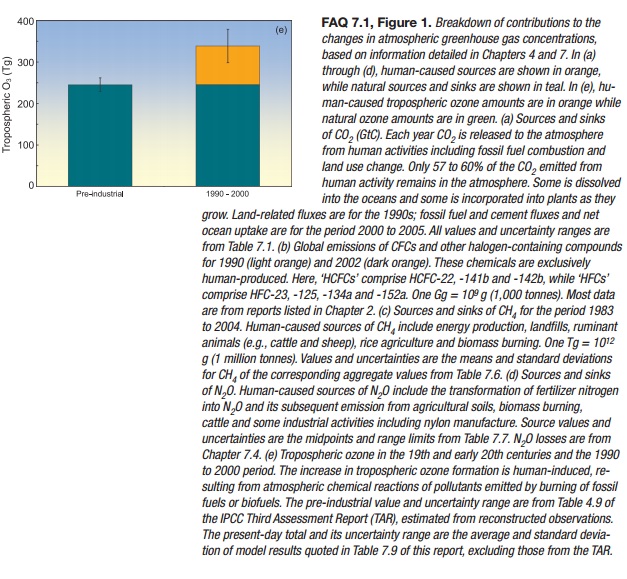

Tropospheric Ozone

Tropospheric ozone is produced by photochemical reactions in

the atmosphere involving forerunner chemicals such as carbon monoxide, CH4,

volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides. These chemicals are emitted by

natural biological processes and by human activities including land use change

and fuel combustion. Because tropospheric ozone is relatively short-lived,

lasting for a few days to weeks in the atmosphere, its distributions are highly

variable and tied to the abundance of its forerunner compounds, water vapour

and sunlight. Tropospheric ozone concentrations are significantly higher in

urban air, downwind of urban areas and in regions of biomass burning. The

increase of 38% (20-50%) in tropospheric ozone since the pre-industrial era

(Figure 1e) is human-caused.

It is very likely that the increase in the combined radiative

forcing from CO2, CH4 and N2O was at least six times faster between 1960 and

1999 than over any 40-year period during the two millennia prior to the year

1800.

Related Topics