Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Anxiolytic Drugs

Anxiolytic Drugs

Anxiolytic Drugs

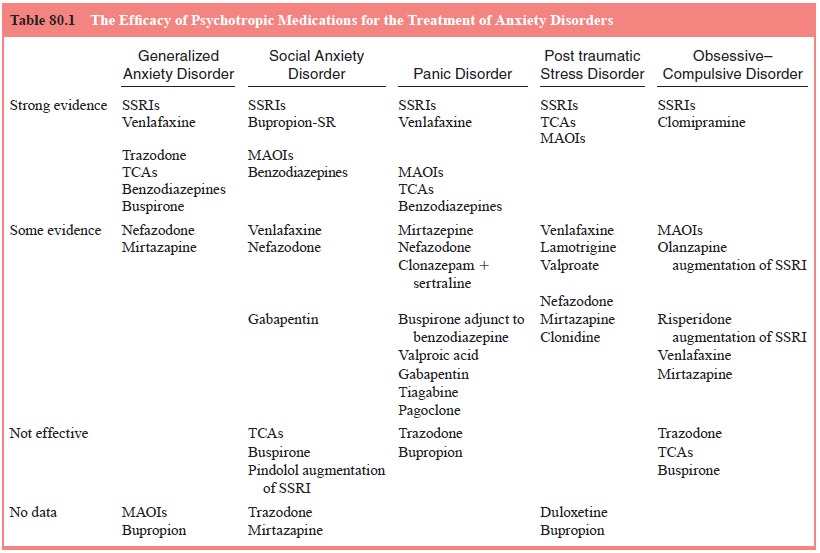

In the

last decade, there has been a substantial increase in the number of medications

demonstrated to be effective for the treat-ment of anxiety and anxiety

disorders (Table 80.1).

There was

a cascade of anxiolytic research in the 1990s. The selective serotonin reuptake

inhibitors (SSRIs) as a class were demonstrated to be efficacious treatments

for most of the anxiety disorders described in the DSM-IV-TR. Although these

agents have a delayed onset when contrasted with the benzodiazepines, they have

a broader spectrum of action, no problems with depen-dence, and much less of a

problem with withdrawal syndromes. The 1990s also saw the approval of

venlafaxine as a treatment for generalized anxiety disorder.

A General Approach to Using Medication with Anxious Patients

Making an

appropriate differential diagnosis which includes a DSMIV-TR anxiety disorder

is critical to the success of any psychopharmacological intervention. The

diagnosis dictates the class of medication to be used and the length of

pharmacother-apy. An important rule in general is “to start low and go slow”

when initiating pharmacological treatment for patients with anxiety disorders.

Interestingly, although treating patients with anxiety disorders frequently

requires a more gradual initial titra-tion schedule, patients frequently attain

maintenance dosages of antidepressant medications that are greater than the

dosage com-monly used to treat major depressive disorder.

Antidepressant Medication

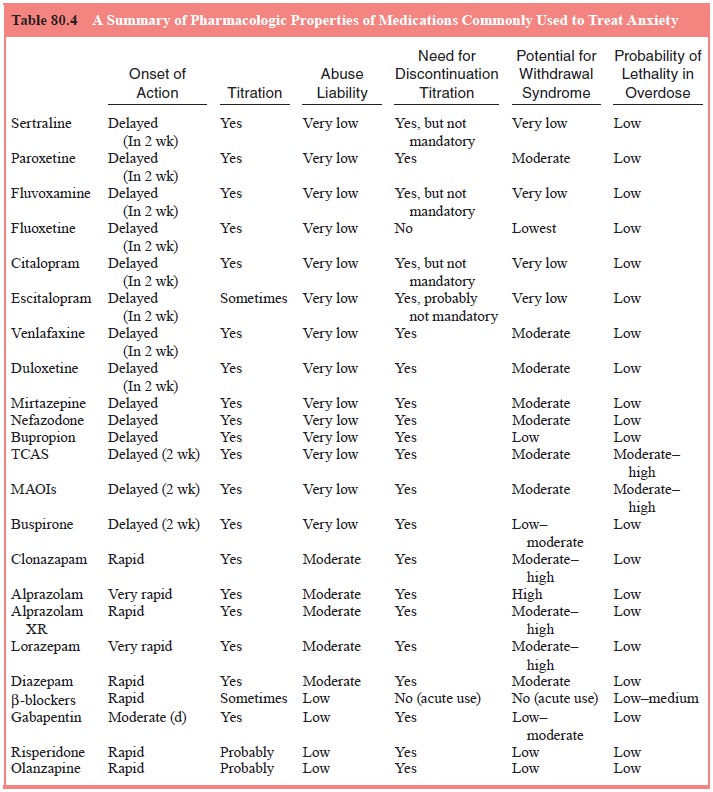

It has

been known that medications initially identified because of their antidepressant

properties are frequently effective treat-ments for anxiety disorders as well.

The basic action of the majority of the antidepressants is to increase the

availability of neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft. These agents have the

broadest spectrum of activity which spans the entire spectrum of DSM-IV-TR

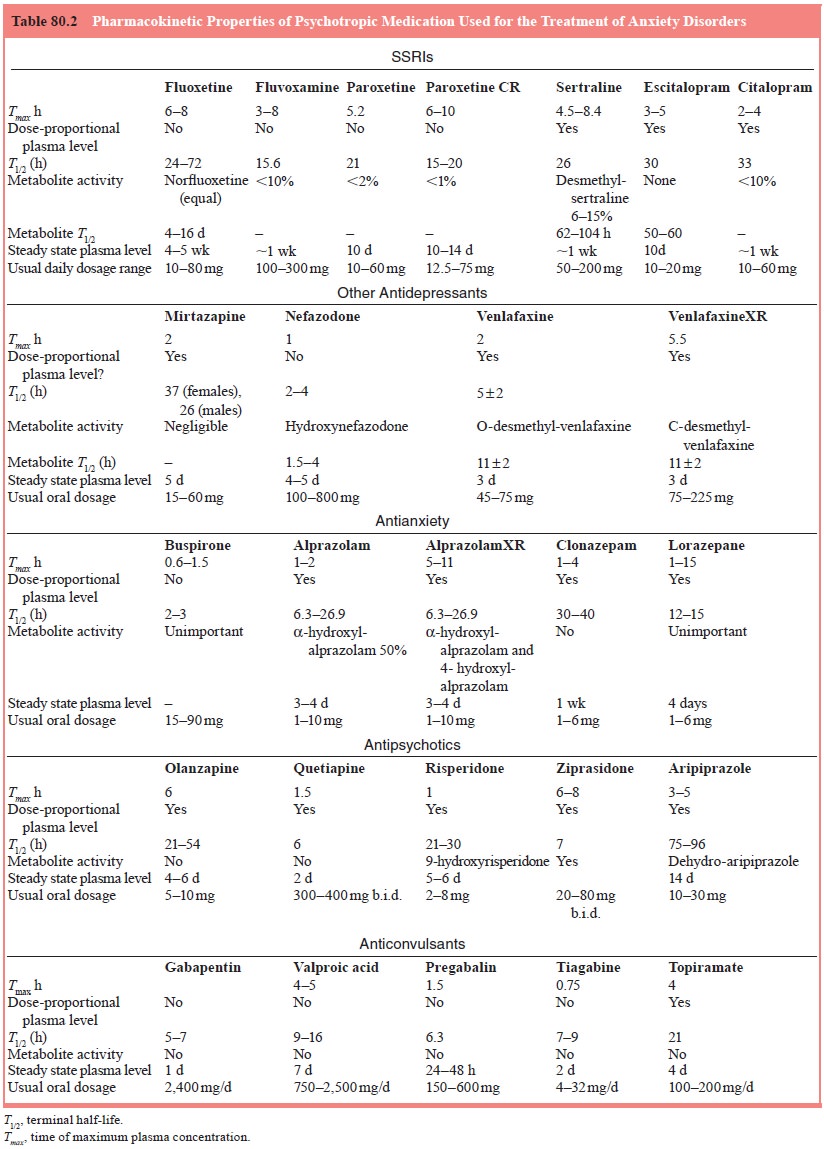

anxiety disorders. The relative differences in terms of major pharmacokinetic

and pharmacodynamic properties are outlined in Tables 80.2 and 80.4. As

illustrated in Table 80.1, a variety of serotonin receptor subtypes have been

implicated in the modulation of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders,

mi-graine, pain and neuropsychiatric disorders.

Indications for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors

Initial

data from randomized, placebo-controlled treatment trials suggest that SSRIs

may be useful in the treatment of adults and children with generalized anxiety

disorder. SSRIs have emerged as a first-line treatment for social anxiety

disorder. Most of the efficacy data are derived from multicenter, double-blind

trials of paroxetine, sertraline and fluvoxamine.

In

addition, SSRIs are generally accepted as a first-line treat-ment for panic

disorder. The major advantage of these agents is their tolerability and thus

longer-term acceptance by patients. There is evidence that fluoxetine,

sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine and citalopram are effective in the acute

treatment of panic disorder.

One of

the advantages of SSRIs is that they tend to be fairly well tolerated in

contrast to some of the other treatments available for panic disorder. Although

a few individuals may have some initial problems with restlessness and

increased anxiety, data suggest that starting at lower doses such as 25 mg/day

of sertraline or 10 mg/day of paroxetine may decrease the risk of

antidepressant “jitteriness”.

There

have been open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled studies demonstrating

that SSRIs are effective for the treatment of post traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD). Open-label trials with all of the SSRIs currently available suggest

that each may be effective in decreasing the core symptoms of PTSD.

Large,

well-designed, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials demonstrate that

fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, cital-opram and sertraline are effective

acute treatments for obses-sive–compulsive disorders.

Indications for Serotonin–Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors in Anxiety Disorders

Venlafaxine

There

have been a number of placebo-controlled multicentered studies demonstrating

that venlafaxine XR is an effective treat-ment of GAD.

Doses as

low as 37.5 mg/day and as high as 225 mg/day are effective in decreasing

symptoms of anxiety for patients with GAD. Side effects appear to be mild and

tend to decrease in num-ber and intensity over the course of treatment. Nausea,

dry mouth and somnolence are the most commonly repeated side effects.

Case

reports and open-label studies have been published for use of venlafaxine in

social anxiety disorder (Kelsey, 1995).

There is

only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Pollack and coworkers.

(1996) suggesting that venlafaxine may be an effective treatment for patients

with panic disorder.

Indications for Tricyclic Antidepressant Medication and Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors in Anxiety Disorders

A variety of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have been dem-onstrated to be effective treatments for GAD. However, the side effects and difficulty titrating the dosage of these medications have made their use uncommon.

In

general, TCAs have not been found to be effective for the treatment of social

anxiety disorder, but there is evidence of effectiveness in panic disorder.

Although surpassed by the SSRIs as first-line agents, there is no doubt that

first-generation MAOIs are effective. Unfortunately, the risk of hypertensive

crisis and the need for patients to follow a tyramine-free diet makes this

class of drugs unappealing for the majority of patients.

Although

TCAs have been widely used for the treatment of panic disorder, their

side-effect profile and slow time to onset of action makes them a difficult

class of medication for many patients to tolerate.

There

have been seven meta-analyses comparing and con-trasting clomipramine and SSRIs

(Abramowitz, 1997; Cox et al., 1993;

Greist, 1998; Kobak et al., 1998;

Piccinelli et al., 1995; Stein et al., 1995). In each case,

clomipramine has been found to be significantly more effective than the SSRIs.

If one takes the entire body of evidence as a whole into account, analyses sug-gest

that clomipramine is at least as effective as the SSRIs and may, in some

instances, be more effective (Greist, 1998; Todorov et al., 2000).

Other Antidepressant Medication (Bupropion, Mirtazapine, Nefazodone, Trazodone) in Anxiety Disorders

Most evidence

fails to support these medications as a first-line treatment for generalized

anxiety disorders, social anxiety disor-der, panic disorder, PTSD, or

obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Benzodiazepine Medication

The

benzodiazepines as a class work by increasing the relative efficiency of the

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor when stimulated by GABA. The

benzodiazepines bind to a site located adjacent to the GABA receptor and cause

an allosteric change to the receptor that facilitates the increased passage of

the chloride ions intracellularly when GABA interacts with the receptor

complex. This leads to a relative hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane

and inhibition of activity in the brain. The benzodiazepines as a group have

different affinities for GABA receptors, in fact some agents bind to only one

of the two types of GABA receptors. The relative pharmacodynamic and

pharmacokinetic properties of the benzodiazepines are fur-ther outlined in

comparison to the other medications in Table 80.2. As a class, benzodiazepines

are efficacious for the treat-ment of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder,

generalized anxiety disorder, alcohol withdrawal and situational anxiety. The

choice of an agent should take into account the age, medical health and comorbid

diagnosis of the patient. Although obses-sive–compulsive disorder falls within

the taxonomy of anxiety disorders, benzodiazepines do not seem to be

particularly effec-tive in treating these patients.

The

limitations to these drugs are the same as when used in any indication. Due to

the potential for abuse and drug with-drawal, their use must be monitored

carefully. This is a particu-larly problematic issue in social anxiety disorder

because of the high rate of comorbid substance abuse. Benzodiazepines may be

best suited for patients with situational and performance anxiety on an

as-needed basis.

The two

high potency benzodiazepines that have been approved by the FDA, alprazolam and

clonazepam are widely used in the treatment of panic disorder. They may also be

help-ful as adjuncts in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, though

not as first-line stand alone treatments.

Buspirone

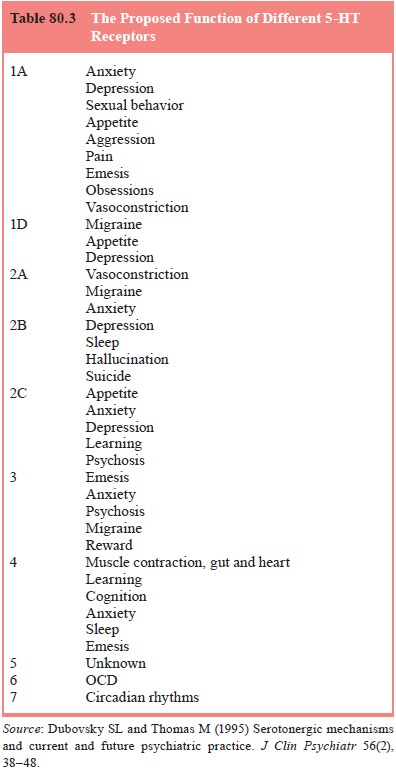

Buspirone

is a member of the group of agents called azaspi-rodecanediones. It is believed

to exert its anxiolytic effect by acting as a partial agonist at the 5-HT1A

autoreceptor. Stimu-lation of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor causes

decrease release of serotonin into the synaptic cleft. However, buspirone also

exerts another effect through its active metabolite 1-phenyl-piperazine (1-PP)

that acts on alpha-2-adrenergic receptors to increase the firing rate of the locus

coeruleus. Some not yet well-characterized

combination of these effects may be responsible for anxiolytic effect of

buspirone. It usually takes approximately 4 weeks for the benefit of buspirone

therapy to be noticed in patients with GAD. It may also be a useful adjuvant in

some patients with treatment resistant panic disor-der. One major advantage of

buspirone is that it does not cross react with benzodiazepines. The most common

side effects associated with buspirone include dizziness, gastrointestinal

distress, headache, numbness and tingling. The most common pharmacokinetic and

pharmacodynamic actions of buspirone are described in Table 80.3.

Beta-blocker Medication

Beta-adrenergic

blockers competitively antagonize norepi-nephrine and epinephrine at the

beta-adrenergic receptor. It is thought that the majority of positive effects

of beta-blockers are due to their peripheral actions. Beta-blockers can

decrease many of the peripheral manifestations of anxiety such as tachy-cardia,

diaphoresis, trembling and blushing. The advent of more selective beta-blockers

that only block the beta-2-adren-ergic receptor has been beneficial since

blockade of beta-1 ad-renergic receptors can be associated with bronchospasm.

Beta-blockers may be useful for individuals who have situational anxiety or

performance anxiety. They generally have not been effective in treating anxiety

disorders such as generalized so-cial anxiety disorder, panic disorder, or

obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Anticonvulsant Medication

One of

the areas of increasing research is the study of an-ticonvulsants in anxiety

disorders. Currently, there are few published placebo-controlled studies

investigating the effi-cacy of commonly used anticonvulsants for the treatment

of anxiety or anxiety disorders. There is one published report of a large

double-blind, placebo-controlled study of gabap-entin for the treatment of

social anxiety disorder. The precise mechanism of action of gabapentin is not

fully appreciated, however, it is thought gabapentin somehow increases brain

GABA levels.

Antipsychotic Medication

The conventional or typical antipsychotic medication whose mechanism of action is primarily to block dopamine Type-2 re-ceptors has been used as adjuvant medication for the treatment of anxiety disorders for years. However, because of problems with extrapyramidal side effects and the risk of developing tardive dyskinesia, these agents had fallen out of favor. The newer class of atypical antipsychotic medications have a decreased risk of both extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia and so antipsychotic medications are beginning to be used again as adju-vants in patients with treatment resistant anxiety disorders. This simultaneous blockade of both neurotransmitter systems seems to decrease extrapyramidal side effects and the risk of develop-ing tardive dyskinesia. Although the different atypical antipsy-chotic medications have different affinities for dopamine Type-2 and serotonin Type-2 receptors, this is the common mechanism of action of these agents. The atypical antipsychotic medica-tions also differ dramatically in terms of their pharmacodynamic properties. There are very few published studies investigating atypical antipsychotic medication augmentation for the treatment of anxiety disorders, so it is not possible to recommend their use as a first-line treatment for anxiety disorders.

Related Topics