Story | By Carl August Sandburg - All Summer in a Day | 12th English : UNIT 5 : Supplementary/Story : All Summer in a Day

Chapter: 12th English : UNIT 5 : Supplementary/Story : All Summer in a Day

All Summer in a Day

Supplementary

All

Summer in a Day

Ray Bradbury

Science Fiction (Sci-fi)

is a genre of speculative fiction, typically dealing with imaginative concepts

such as advanced science and technology, space light, time travels, and

extraterrestrial life. Science Fiction often explores the potential

consequences of scientific and other innovations, and has been called a

‘literature of ideas’.

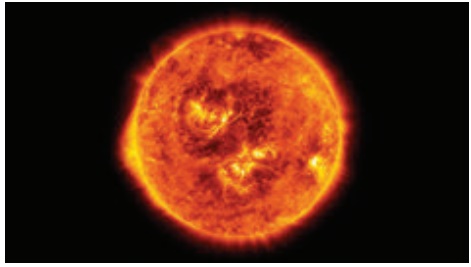

Can you imagine a day

without the Sun?

Here is a Science

Fiction Story that explores the theme of life on Venus, the other Planet, which

as of today is not a possibility.

“Ready?”

“Ready.”

“Now?”

“Soon.”

“Do the scientists really

know? Will it happen today, will it?”

The children pressed to

each other like so many roses, so many weeds, intermixed, peering out for a look at the hidden sun

It rained.

It had been raining for

seven years; thousands upon thousands of days compounded and filled from one

end to the other with rain, with the drum and gush of water, with the sweet

crystal fall of showers and the concussion of storms so heavy that they were tidal waves come over the islands.

A thousand forests had been crushed under the rain and grown up a thousand

times to be crushed again. And this was the way life was forever on the planet

Venus, and this was the schoolroom of the children of the rocket men and women

who had come to the raining world to set up civilization and live out their

lives.

“It’s stopping, it’s

stopping !”

“Yes, yes !”

Margot stood apart from

them, from these children who could ever remember a time when there wasn’t rain

and rain and rain. They were all nine years old, and if there had been a day,

seven years ago, when the sun came out for an hour and showed its face to the

stunned world, they could not recall. Sometimes, at night, she heard them stir,

in remembrance, and she knew they were dreaming and remembering gold or a

yellow crayon or a coin large enough to buy the world with. She knew they

thought they remembered a warmness, like a blushing in the face, in the body,

in the arms and legs and trembling hands. But then they always awoke to the

tatting drum, the endless shaking down of clear bead necklaces upon the roof,

the walk, the gardens, the forests,and their dreams were gone.

All day yesterday they

had read in the class about the sun. About how like a lemon it was, and how

hot. And they had written small stories or essays or poems about it: I think

the sun is a flower,That blooms for just one hour. That was Margot’s poem,

read in a quiet voice in the still classroom while the rain was falling

outside.

“Aw, you didn’t write

that!” protested one of the boys.

“I did,” said Margot. “I

did.”

“William!” said the

teacher.

But that was yesterday.

Now the rain was slackening, and the children were crushed in the great thick windows.

“Where’s teacher ?”

“She’ll be back.”

“She’d better hurry,

we’ll miss it !”

They turned on

themselves, like a feverish wheel, all tumbling spokes. Margot stood alone. She

was a very frail girl who looked as if she had been lost in the rain for years

and the rain had washed out the blue from her eyes and the red from her mouth

and the yellow from her hair. She was an old photograph dusted from an album,

whitened away, and if she spoke at all her voice would be a ghost. Now she

stood, separate, staring at the rain and the loud wet world beyond the huge

glass.

“What’re you looking

at?” said William.

Margot said nothing.

“Speak when you’re spoken

to.”

He gave her a shove. But she did not move;

rather she let herself be moved only by him and nothing else. They edged away

from her, they would not look at her. She felt them go away. And this was

because she would play no games with them in the echoing tunnels of the

underground city. If they tagged her and ran, she stood blinking after them and

did not follow. When the class sang songs about happiness and life and games

her lips barely moved. Only when they sang about the sun and the summer did her

lips move as she watched the drenched windows. And then, of course, the biggest

crime of all was that she had come here only five years ago from Earth,and she

remembered the sun and the way the sun was and the sky was when she was four in

Ohio. And they, they had

been on Venus all their lives, and they had been only two years old when last

the sun came out and had long since forgotten the colur and heat of it and the

way it really was.

But Margot remembered.

“It’s like a penny,” she

said once, eyes closed.

“No it’s not!” the

children cried.

“It’s like a fire,” she

said, “in the stove.”

“You’re lying, you don’t

remember !” cried the children.

But she remembered and

stood quietly apart from all of them and watched the patterning windows. And once, a

month ago, she had refused to shower in the school shower rooms, had clutched her hands to her ears

and over her head, screaming the water mustn’t touch her head. So after that,

dimly, dimly, she sensed it, she was different and they knew her difference and

kept away. There was talk that her father and mother were taking her back to

Earth next year; it seemed vital to her that they do so,though it would mean

the loss of thousands of dollars to her family. And so, the children hated her

for all these reasons of big and little consequence. They hated her pale snow

face, her waiting silence, her thinness, and her possible future.

“Get away!” The boy gave

her another push. “What’re you waiting for?”

Then, for the first

time, she turned and looked at him. And what she was waiting for was in her

eyes.

“Well, don’t wait around

here !” cried the boy savagely. “You won’t see nothing!”

Her lips moved.

“Nothing!” he cried. “It

was all a joke,wasn’t it?” He turned to the other children.

“Nothing’s happening

today. Is it ?”

They all blinked at him

and then, understanding, laughed and shook their heads.

“Nothing, nothing !”

“Oh, but,” Margot whispered, her eyes helpless.

“But this is the day, the scientists predict, they say, they know, the sun…”

“All a joke!” said the

boy, and seized her roughly. “Hey, everyone, let’s put her in a closet before

the teacher comes!”

“No,” said Margot,

falling back.

They surged about her, caught her

up and bore her, protesting, and then pleading, and then crying, back into a

tunnel, a room, a closet, where they slammed and locked the door. They stood looking at the door and

saw it tremble

from her beating and

throwing herself against it. They heard her muffled cries. Then, smiling, they turned and went out

and back down the tunnel, just as the teacher arrived.

“Ready, children ?” She

glanced at her watch.

“Yes!” said everyone.

“Are we all here ?”

“Yes!”

The rain slacked still

more.

They crowded to the huge

door.

The rain stopped.

It was as if, in the

midst of a film concerning an avalanche, a tornado, a hurricane, a volcanic eruption,

something had, first, gone wrong with the sound apparatus, thus muffling and

finally cutting off all noise, all of the blasts and repercussions and thunders, and then, second, ripped the film

from the projector and inserted in its place a beautiful tropical slide which

did not move or had a tremor. The world ground to a standstill. The silence was so immense and

unbelievable that you felt your ears had been stuffed or you had lost your

hearing altogether. The children put their hands to their ears. They stood

apart. The door slid back and the smell of the silent, waiting world came in to

them.

The sun came out.

It was the colour of

flaming bronze and it was very large. And the sky around it was a blazing blue

tile colour. And the jungle burned with sunlight as the children, released from

their spell, rushed out, yelling

into the spring time.

“Now, don’t go too far,”

called the teacher after them. “You’ve only two hours, you know. You wouldn’t

want to get caught out!”

But they were running

and turning their faces up to the sky and feeling the sun on their cheeks like

a warm iron; they were taking off their jackets and letting the sun burn their

arms.

“Oh, it’s better than

the sun lamps, isn’t it?”

“Much, much better!”

They stopped running and

stood in the great jungle that covered Venus, that grew and never stopped

growing, tumultuously, even as you watched it. It was a nest of octopi, clustering up great

arms of flesh like weed, wavering, flowering in this brief spring. It was the

colour of rubber and ash, this jungle, from the many years without sunlight was

the colour of stones and white cheeses and ink, and it was the colour of the

moon.

The children lay out,

laughing, on the jungle mattress, and heard it sigh and squeak under them resilient and alive. They ran

among the trees, they slipped and fell, they pushed each other, they played

hide-and-seek and tag, but most of all they squinted at the sun until tears ran down their faces;

they put their hands up to that yellowness and that amazing blueness and they

breathed of the fresh, fresh air and listened and listened to the silence which

suspended them in a blessed sea of no sound and no motion. They looked at

everything and savoured everything. Then, wildly, like animals escaped from

their caves, they ran and ran in shouting circles. They ran for an hour and did

not stop running.

And then –

In the midst of their

running one of the girls wailed.

Everyone stopped.

The girl, standing in

the open, held out the other hand.

“Oh, look, look,” she

said, trembling.

They came slowly to look

at her opened palm.

In the centre of it,

cupped and huge, was a single raindrop. She began to cry, looking at it. They

glanced quietly at the sun.

“Oh. Oh.”

A few cold drops fell on

their noses and their cheeks and their mouths. The sun faded behind a stir of

mist. A wind blew cold around them. They turned and started to walk back toward

the underground house, their hands at their sides, their smiles vanishing away.

A boom of thunder

startled them and like leaves before a new hurricane, they tumbled upon each

other and ran.

Lightning struck ten

miles away, five miles away, a mile, a half mile. The sky darkened into

midnight in a flash.

They stood in the

doorway of the underground for a moment until it was raining hard. Then they

closed the door and heard the gigantic sound of the rain falling in tons and

avalanches, everywhere and forever.

“Will it be seven more

years?” “Yes. Seven.”

Then one of them gave a

little cry.

“Margot!

“What?”

“She’s still in the

closet where we locked her.”

“Margot.”

They stood as if someone

had driven them, like so many stakes, into the floor. They looked at each other

and then looked away. They glanced out at the world that was raining now and raining

and raining steadily. They could not meet each other’s glances. Their faces

were solemn and pale. They looked

at their hands and feet, their faces down.

“Margot.”

One of the girls said,

“Well… ?” No one moved.

“Go on,” whispered the

girl.

They walked slowly down

the hall in the sound of cold rain. They turned through the doorway to the room

in the sound of the storm and thunder, lightning on their faces, blue and

terrible. They walked over to the closet door slowly and stood by it.

Behind the closet door

was only silence.

They unlocked the door,

even more slowly, and let Margot out.

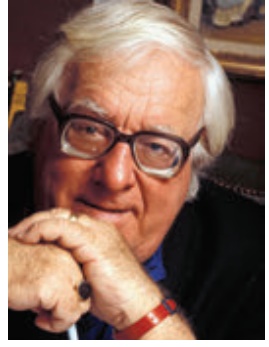

About The Author

Ray Douglas Bradbury (August 22, 1920

– June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. He worked in a variety

of genres, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, and fiction. Widely

regarded as the most important figure in the development of science fiction as

a literary genre, Ray Bradbury’s works evoke the themes of racism, censorship,

technology, nuclear war, humanistic values and the importance of imagination.

Ray Bradbury is well-known for his incredibly descriptive style. He employs

figurative language (mostly similes, metaphors, and personification) throughout

the novel and enriches his story with symbolism. On April 16, 2007, Bradbury

received a special citation from the Pulitzer Prize jury “for his

distinguished, prolific, and deeply influential career as an unmatched author

of science fiction and fantasy.” Bradbury also wrote and consulted on

screenplays and television scripts, including Moby Dick and It Came from

Outer Space. Many of his works were adapted to comic book, television, and

film formats.

Related Topics