Chapter: Software Design : General Design Fundamentals

Software Design: Classes and Objects

Classes and Objects

An object has state, behavior, and identity; the structure and behavior

of similar objects are defined in their common class; the terms instance and

object are interchangeable.

The state of an object encompasses all of the (usually static)

properties of the object plus the current(usually dynamic) values of each of

these properties.

The Meaning of Behavior No object exists in isolation. Rather, objects

are acted upon, and themselves act upon other objects. Thus, we may say that

Behavior is how an object acts and reacts, in terms of its state changes and

message passing.

―Identity

is that property of an object which distinguishes it from all other objects‖

Relationships Among Objects

The relationship between any two objects encompasses the assumptions

that each makes about the other, including what operations can be performed and

what behavior results. We have found that two kinds of object hierarchies are

of particular interest in object-oriented analysis and design, namely:

• Links

• Aggregation

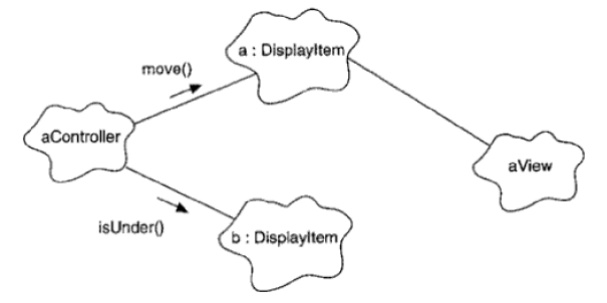

Figure Link

Link is a

"physical or conceptual connection between objects". An object

collaborates with other objects through its links to these objects.

A line

between two object icons represents the existence of a link between the two and

means that messages may pass along this path. Messages are shown as directed

lines representing the direction of the message, with a label naming the

message itself. For example, here we see that the object a Controller has links to two instances of Display Item (the objects a

and b). Although both a and b probably have links to the view in which they are shown, we have

chosen to highlight only once such

link, from a to a View. Only across these links may one object send messages to

another.

As a

participant in a link, an object may play one of three roles:

• Actor

An object that can operate upon other objects but is never operated upon by

other objects; in some contexts, the terms active object and actor are

interchangeable

• Server An

object that never operates upon other objects; it is only operated upon by

other objects

• Agent An

object that can both operate upon other objects and be operated upon by other

objects;

an agent is usually created to do some work on behalf of an actor or another

agent

The Nature of a Class

A class

is a set of objects that share a common structure and a common behavior.

The concepts of a class and an object are tightly interwoven, for we

cannot talk about an object without regard for its class. However, there are

important differences between these two terms. Whereas an object is a concrete

entity that exists in time and space, a class represents only an abstraction,

the ―essence" of an object, as it were. Thus, we may speak of the class Mammal, which represents the

characteristics common to all mammals. To identify a particular mammal in this

class, we must speak of "this mammal‖ or "that mammal."

The interface of a class provides its outside view and therefore

emphasizes the abstraction while hiding its structure and the secrets of its

behavior. This interface primarily consists of the declarations of all the

operations applicable to instances of this class, but it may also include the

declaration of other classes, constants, variables, and exceptions as needed to

complete the abstraction. By contrast, the implementation of a class is its

inside view, which encompasses the secrets of its behavior. The implementation

of a class primarily consists of the implementation of all of the operations

defined in the interface of the class.

We can

further divide the interface of a class into three parts:

• Public A

declaration that is accessible to all clients

• Protected

A declaration that is accessible only to the class itself, its subclasses, and

its friends

• Private A

declaration that is accessible only to the class itself and its friends

Relationships Among Classes

Kinds of Relationships

Consider for a moment the similarities and differences among the

following classes of objects: flowers, daisies, red roses, yellow roses,

petals, and ladybugs. We can make the following observations:

• A daisy

is a kind of flower.

• A rose is

a (different) kind of flower.

• Red roses

and yellow roses are both kinds of roses.

• A petal

is a part of both kinds of flowers.

• Ladybugs

eat certain pests such as aphids, which may be infesting certain kinds of

flowers.

From this simple example we conclude that classes, like objects, do not

exist in isolation. Rather, for a particular problem domain, the key

abstractions are usually related in a variety of interesting ways, forming the

class structure of our design. We establish relationships between two classes

for one of two reasons. First, a class relationship might indicate some sort of

sharing. For example, daisies and roses are both kinds of flowers, meaning that

both have brightly colored petals, both emit a fragrance, and so on. Second, a

class relationship might indicate some kind of semantic connection. Thus, we

say that red roses and yellow roses are more alike than are daisies and roses,

and daisies and roses are more closely related than are petals and flowers.

Similarly, there is a symbiotic connection between ladybugs and flowers:

ladybugs protect flowers from certain pests, which serve as a food source for

the ladybug.

In all, there are three basic kinds of class relationships. The first of

these is generalization/specialization, denoting an "is a"

relationship. For instance, a rose is a kind of flower, meaning that a rose is

a specialized subclass of the more general class, flower. The second is

whole/part, which denotes a "part of" relationship. Thus, a petal is

not a kind of a flower; it is a part of a flower. The third is association,

which denotes some semantic dependency among otherwise unrelated classes, such

as between ladybugs and flowers. As another example, roses and candles are

largely independent classes, but they both represent things that we might use

to decorate a dinner table.

Several common approaches have evolved in programming languages to

capture generalization/specialization, whole/part, and association

relationships. Specifically, most object-oriented languages provide direct

support for some combination of the following relationships:

Related Topics