Chapter: Clinical Dermatology: The skin and the psyche

Reactions to skin disease

Reactions

to skin disease

The

presence of disfiguring skin lesions can distort the emotional development of a

child: some become withdrawn, others become aggressive, but many adjust well.

The range of reactions to skin disease is therefore wide. At one end lies

indifference to grossly disfiguring lesions and, at the other, lies an

obsession with skin that is quite normal. Between these extremes are reactions

ranging from natural anxiety over ugly skin lesions to disproportionate worry over

minor blemishes.

A

chronic skin disease such as psoriasis can undoubtedly spoil the lives of those

who suffer from it. It c interfere with work, and with social activities of all

sorts including sexual relationships, causing sufferers to feel like outcasts.

The heavy drinking of so many men with severe psoriasis is one result of these

pressures. An experienced dermatologist will be on the lookout for depression

and the risk of suicide, as up to 10% of patients with psoriasis have had

suicidal thoughts. However, these reactions do not necessarily correlate with

the extent and severity of the eruption as judged by an outside observer. Who

has the more disabling problem: someone with 50% of his body surface covered in

psoriasis, but who largely ignores this and has a happy family life and a

productive job, or one with 5% involvement whose social life is ruined by it?

The concept of ‘body image’ is useful here.

Body image

All

of us think we know how we look, but our ideas may not tally with those of

others. The nose, face, hair and genitals tend to rank high in a person’s

‘corporeal awareness’, and trivial lesions in those areas can gen-erate much

anxiety. The facial lesions of acne, for example, can lead to a huge loss of

self-esteem.

Dermatological delusional disease

Dysmorphophobia

This

is the term applied to distortions of the body image. Minor and inconspicuous

lesions are magnified in the mind to grotesque proportions.

Dermatological ‘non-disease’

This

is a form of dysmorphobia. The clinician can find no skin abnormality, but the

distress felt by the patient leads to anxiety, depression or even suicide. Such

patients are not uncommon. They expect derma-tological solutions for complaints

such as hair loss, or burning, itching and redness of the face or genitals. The

dermatologist, who can see nothing wrong, can-not solve matters and no

treatment seems to help. Such patients are reluctant to see a psychiatrist

although some may suffer from a monosymptomatic hypochond-riacal psychosis.

Other delusions

These

patients sustain single hypochondriacal delusions for long periods, in the

absence of other recognizable psychiatric disease. Some are eccentric and live

in social isolation. Some believe that they have syphilis, AIDS or skin cancer.

In dermatology, many of these patients have the delusion that their skin is

infested with parasites.

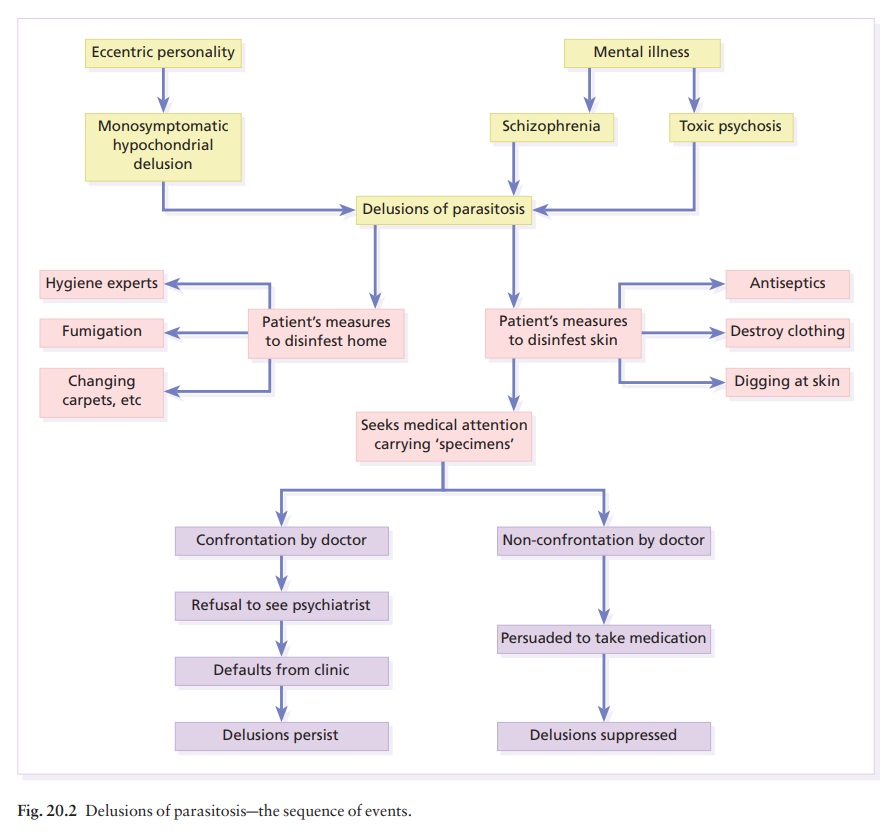

Delusions of parasitosis (Fig.

20.2)

This

term is better than ‘parasitophobia’, which implies a fear of becoming

infested. Patients with delusions of parasitosis are unshakably convinced that

they are already infested. No rational argument can convince them that they are

not; the pest control agencies that they have called in, and their medical

advisers therefore must both be wrong. Symptoms include odd sensations of

crawling and biting, and patients often bring to the clinic a box of specimens

of the ‘parasite’ at different stages of its supposed life cycle. These must be

examined microscopically but usually turn out to be fragments of skin, hair,

cloth-ing, haemorrhagic crusts or unclassifiable debris. The skin changes may

include gouge marks and scratches, but it is convenient to consider these

patients separately from those with dermatitis artefacta.

These

patients become angry if doubts are cast on their ideas, or if they are referred

to a psychiatrist. How could treatment for mental illness possibly be expected

to kill parasites? Family members may share their delusions and much tact is

needed to secure any cooperation with treatment. Direct confrontations are best

avoided; sometimes it may be best simply to treat with psychotropic drugs,

explaining that these may be able to help some of the symptoms.

The

delusions of a few of these patients are based on an underlying depression or

schizophrenia, and of a further few on organic problems such as vitamin

deficiency or cerebrovascular disease. These disorders must be treated on their

own merits. However, most patients suffer from monosymptomatic hypochon-driacal

delusions, which can often be suppressed by treatment with drugs, accepting

that these will be needed long-term. Otherwise, the outlook for resolu-tion is

poor. Pimozide was once the most popular treatment for this condition but high

doses carry car-diac risks. If pimozide is used, an electrocardiogram (ECG)

should be performed before starting treatment and the drug should not be given

to those with a prolonged Q-T interval or with a history of cardiac

dysrhythmia. Patients on pimozide in excess of 16 mg daily need periodic ECG

checks. Tardive dyskinesia may develop and persist despite withdrawal of the

drug. Risperidone, olanzapine and sulpiride are reasonable, and perhaps safer,

alternatives. Some patients gain insight and relief. Others hint that their

parasites still persist although this no longer disables them.

Dermatitis artefacta

Here the skin lesions are caused and kept going by the patient’s own actions, but parasites are not held to be to blame. Patients with dermatitis artefacta deny self-trauma but, naturally, if treatment is left to them to carry out, their problems do not improve. Lesions will heal under occlusive dressings, but this does not alter the underlying psychiatric problems, and lesions may recur or crop up outside the bandaged areas. Different types of dermatitis artefacta are listed in Table 20.1.

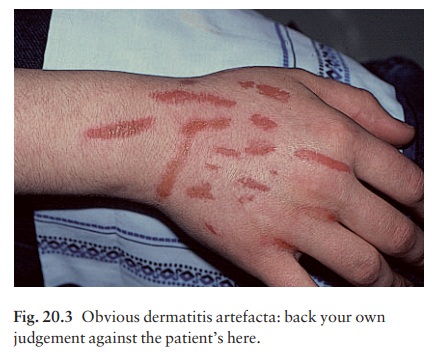

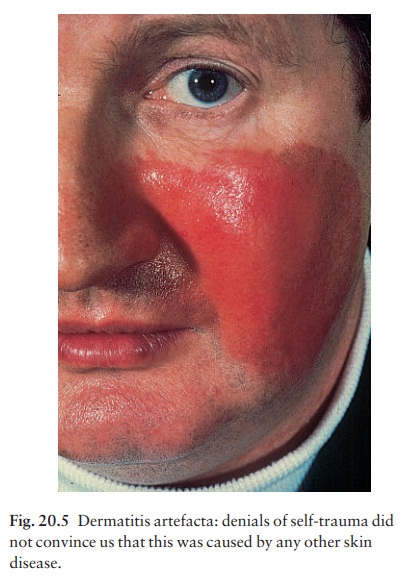

The

lesions favour accessible areas, and do not fit with known pathological

processes. The diagnosis is often difficult to make, but an experienced

clinician will suspect it because there are no primary lesions and because of

the bizarre shape or grouping of the lesions, which may be rectilinear or oddly

grouped (Fig. 20.3). Areas damaged by burning (Fig. 20.4), corrosive chemicals

(Fig. 20.5), or by digging have their own special appearance.

More subtle changes are seen in ‘dermatological pathomimicry’, in which patients reproduce or ag-gravate their skin disease by deliberate contact with materials to which they know they will react.

Apart from frank malingerers, the patients are often young women with some medical knowledge, perhaps a nurse. Some form of ‘secondary gain’ from having skin lesions may be obvious. The psycholo-gical problems may be superficial and easily resolved, but sometimes psychiatric help is needed and the artefacts are part of a prolonged psychiatric illness. A few patients respond to banal treatments if given the chance to save face. Direct confrontation and accusations are usually best avoided, and the con-dition may last for some years.

Neurotic excoriations

Patients

with neurotic excoriations differ from those with other types of dermatitis

artefacta in that they admit to picking and digging at their skin. This habit

affects women more often than men and is most active at times of stress. The

clinical picture is mixed, with crusted excoriations and pale scars, often with

a hyperpigmented border, lying mainly on the face, neck, shoulders and arms

(Fig. 20.6). The condition may last for years and psychiatric treatment is

seldom successful.

Acne excoriée

Here

the self-inflicted damage is based to some extent on the lesions of acne

vulgaris, which may in them-selves be mild, but become disfiguring when dug and

squeezed to excess. The patients are usually young girls who may leave

themselves with ugly scars. A psychiatric approach is often unhelpful and a

daily ritual of attacking the lesions, helped by a magnifying mirror, may

persist for years.

Localized neurodermatitis (lichen simplex)

This

term refers to areas of itchy lichenification, per-petuated by bouts of

scratching in response to stress. The condition is not uncommon and can occur on

any area of skin. In men, lesions are often on the calves; in women, they

favour the nape of the neck where the redness and scaling look rather like

psoriasis. Some examples of persistent itching in the anogenital area are

caused by lichen simplex there.

Patients

with localized neurodermatitis develop scratch responses to minor itch stimuli

more readily than controls. Local therapy does not alter the under-lying cause,

but topical steroids, sometimes only the most potent ones, ameliorate the

symptoms. Occlusive bandaging of suitable areas clears only those lesions that

are covered.

Nodular

prurigo (Fig. 20.7) may be a variant on this theme as manifested in atopic

subjects, who scratch and rub remorselessly at their extremely itchy nodules.

Hair-pulling habit

Trichotillomania

is too dramatic a word for what is usually only a minor comfort habit in

children, rank-ing alongside nail-biting and lip-licking. Perhaps the term

should be dropped in favour of ‘hair-pulling habit’. It is usually of little

consequence, and children who twist and pull their hair, often as they are

going to sleep, seldom have major psychiatric disorders. The habit often goes

away most quickly if it is ignored. However, more severe degrees of

hair-pulling are some-times seen in disturbed adolescents and in those with

learning difficulties; then the outlook for full regrowth is less good, even

with formal psychiatric help.

The

diagnosis can usually be made on the history, but some parents do not know what

is going on. The bald areas do not show the exclamation-mark hairs of alopecia

areata, or the scaling and inflammation of scalp ringworm. The patches are

irregular in outline and hair loss is never complete. Those hairs that remain

are bent or broken, and of variable length.

Related Topics