Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Psychiatric Pathophysiology: Mood Disorders

Monoamine Alterations

Monoamine Alterations

Serotonergic System

Serotonin has been implicated in the

pathophysiology of depression and bipolar disorder (for reviews, see Mann,

1999; Oquendo and Mann, 2000; Shiah and Yatham, 2000; Mann et al., 2001; Nemeroff et al.,

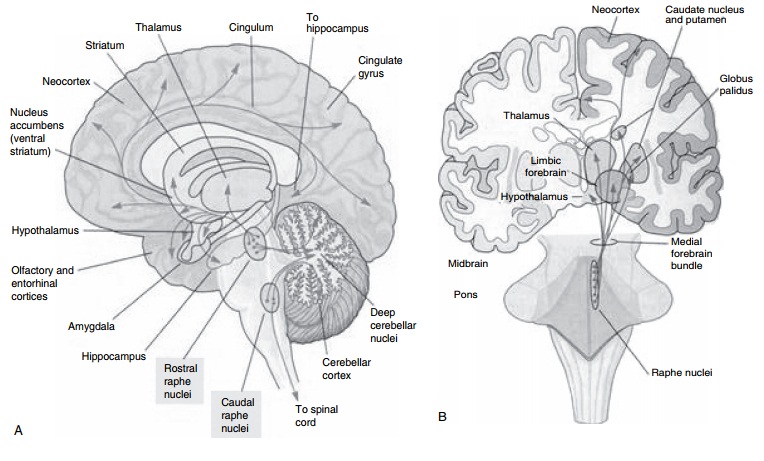

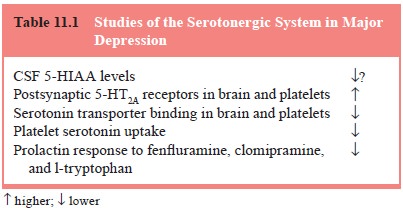

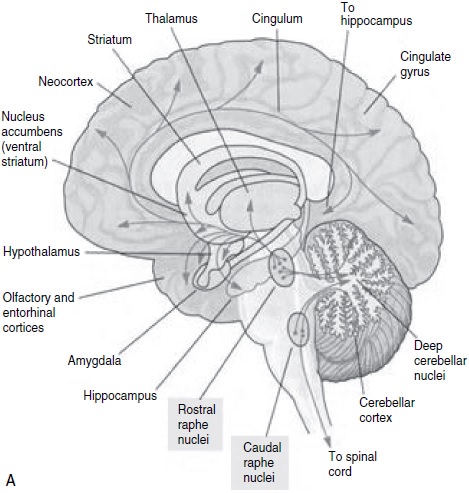

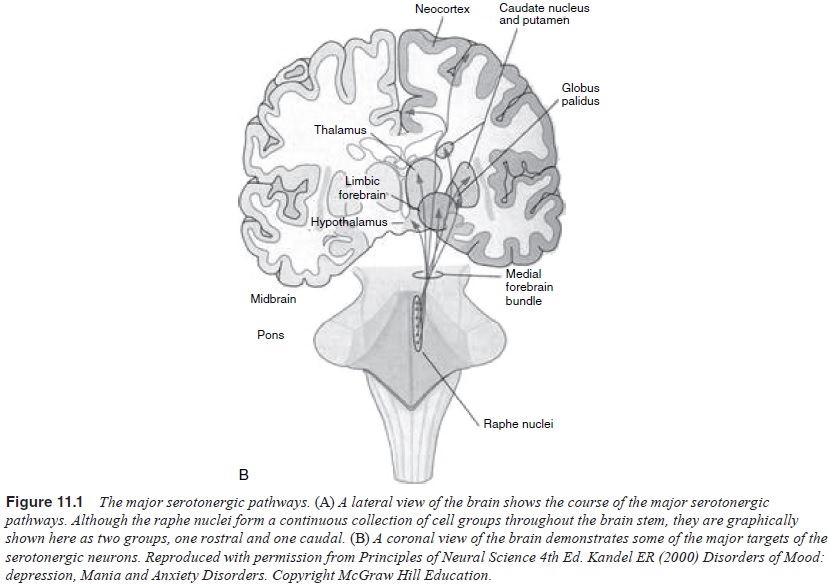

1997; Meltzer and Lowy, 1987; Coppen, 1969; Mace and Taylor, 2000; Kandel, 2000; Charney et al., 1981) (Table 11.1 and Figure 11.1). This hypothesis

proposed that the vulnerability to either depression or mania was related to

low serotonergic activity, attrib-utable to either less serotonin release or

fewer serotonin receptors or impaired serotonin receptor-mediated signal

transduction. Prange et al., (1974) formulated a permissive

hypothesis of serotonin function in

bipolar disorder. They suggested that a deficit in central seroton-ergic neurotransmission

permits the expression of bipolar disorder, and that both the manic and

depressive phases of bipolar disorder are characterized by low central

serotonergic neurotransmission. Over the last 30 years, a variety of studies of

the serotonergic sys-tem have reinforced its role in major depression and

identified ad-ditional associations with suicidal behavior, impulsivity,

aggression, eating disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders,

personality disorders, seasonal changes in mood and behavior, and alcohol abuse

and dependence. The serotonergic system also plays a role in the regulation of

a variety of basic biological functions in-cluding sleep, appetite, circadian

rhythm and cognitive function.

Medications that target the serotonin transporter

site and se-lectively inhibit reuptake of serotonin (e.g., fluoxetine,

sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram) have all been shown to be

effective antidepressants (Nemeroff et al.,

1997; Sampson, 2001;

Mace and Taylor, 2000). Some antidepressant drugs

specifically act at one of the many serotonin receptor subtypes. For example,

suggested antidepressive/anxiolytic medications buspirone and gepirone are 5-HT1A

receptor agonists, and fewer 5-HT1A receptors are implicated in the

pathophysiological mechanism of depression and anxiety (Yocca, 1990; Apter and

Allen, 1999).

Considered together, studies of serotonin function

in major depression suggest both hypofunction and likely compensatory changes

that would increase serotonergic activity (Brown et al., 1994; Leonard, 1994; Dubovsky and Buzan, 1999). Findings

such as 1) lower serotonin and 5-HIAA levels in postmortem brain stem and lower

CSF 5-HIAA; 2) relapse of depression with diet acute depletion of tryptophan;

3) fewer serotonin transporter sites in prefrontal cortex; 4) fewer

postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors; and 5) the antidepressant properties

of medications that enhance serotonergic transmission suggest that

underactivity of the serotonin system is part of the pathogenesis of

depression. Conversely, more 5-HT2A receptor binding in the frontal

cortex of depressed individuals who committed suicide, fewer brainstem 5-HT1A

autoreceptors and fewer serotonin transporters in the raphe nuclei would tend

to increase serotonergic transmission in major depression. There is evidence

for the contribution of serotonin in mania and in the mechanism of action of

mood stabilizers (Shiah and Yatham, 2000); however, the data on the role of the

serotonergic system in mania are fewer and not consistent. Alterations in

functioning of other neurotransmitters in mania such as norepinephrine, dopamine,

acetylcholine and GABA, and their interaction with serotonin may also

contribute. Future studies of serotonergic activity in mood disorders will need

further to differentiate primary pathogenesis from compensatory changes.

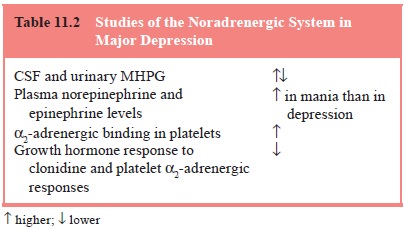

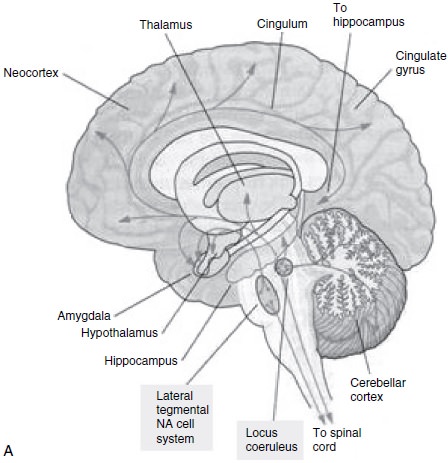

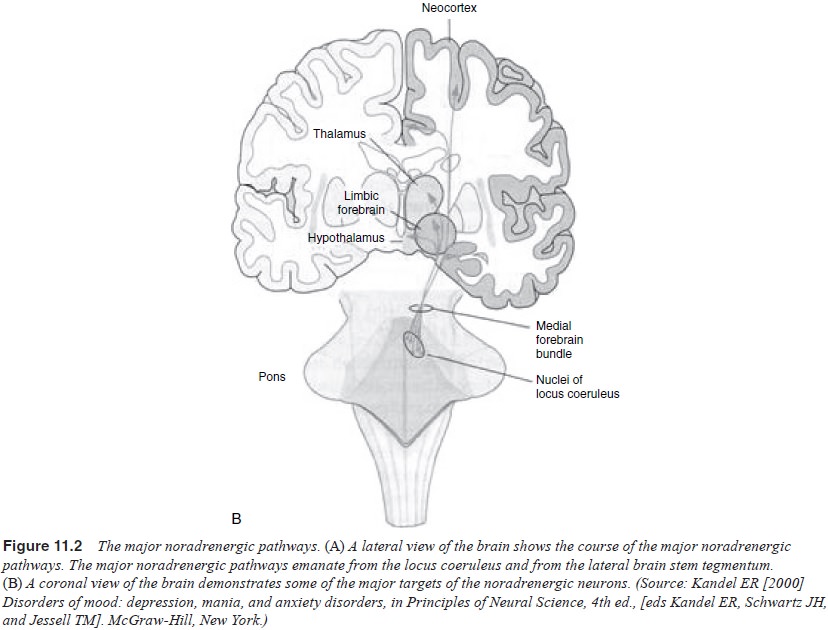

Noradrenergic System

There are multiple lines of evidence that the

noradreneric system is disordered in depression (Berman et al., 1996; Charney, 1998; He-ninger et al., 1996; Leonard, 1997; Owens, 1997; Kandel, 2000; Pot-ter et al., 1993; Schatzberg and

Schildkraut, 1995; Nemeroff et al.,

1997; Ressler and Nemeroff, 1999) (Table 11.2 and Figure 11.2).

A large body of metabolite data are consistent with

the hy-pothesis that there are abnormalities in the noradrenergic system in

depression. The conflicting findings, however, are not consist-ent with simple

increased or decreased noradrenergic activity.

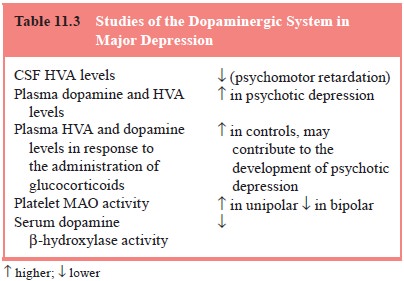

Dopaminergic System

Some studies have found that CSF levels of the

dopamine metabolite homovanillic acid (HVA) are lower in patients with major

depression than in controls and that lower CSF HVA levels are found in more

severely depressed patients (see Kapur and Mann, 1992; Brown et al.,

1994, for a summary) (Table 11.3). However, other studies failed to replicate these findings or found

higher CSF HVA in patients with depression (Jimerson, 1987; Vestergaard et al., 1978).

Gamma-aminobutyric Acid

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major

inhibitory neu-rotransmitter in almost all areas of the CNS and regulates many

CNS functions (Nemeroff et al.,

1997). A decrease in GABAergic activity may play a role in depression by

regulating receptor re-sponses to catecholamines (Enna et al., 1986; Nemeroff et al.,

1997). Pathophysiological contributions of GABA and thera-peutic effects of

GABAergic medications in mood disorders may be mediated via effects on other

neurotransmitter systems (Dubovsky and Buzan, 1999; Nemeroff et al., 1997).

Other Neurotransmitters

Cholinergic neurons containing acetylcholine

project diffusely throughout the cortex (Thase, 2000). The involvement of

cholinergic system in the pathogenesis of depression is supported by the

following findings: cholinergic input reduces REM latency (decreased REM

la-tency is seen in depression); some antidepressants have anticholiner-gic

properties; lecithin, an acetylcholine precursor, reduces mania in some cases

and can induce depression; and cholinergic rebound fol-lowing abrupt withdrawal

of anticholinergic medications can cause a relapse of depression (Dubovsky and

Buzan, 1999; Dilsaver and Coffman, 1989; Janowsky and Risch, 1984; Keshavan,

1985).

There are emerging data that drugs that antagonize

NMDA receptors have antidepressant effects (Przegalinski et al., 1997; Papp and Moryl, 1994; Trullas and Skolnick, 1990).

It is important to note that all neurotransmitters

and receptors interact with and influence each other (Brown et al., 1994; Leonard, 1994; Dubovsky

and Buzan, 1999). Most cerebral functions are the result of the converging

action of many different neurotransmitters. It is not likely that the

pathophysiology of mood disorders is due to a single neurotransmitter (Brown et al., 1994). More probably, mood

disorders are disorders of the overall interaction of multiple transmitter

systems. Alternatively, different components of depres-sion may be related to

different neurotransmitter dysfunction.

The binding of a neurotransmitter to a postsynaptic

receptor triggers a cascade of chemical processes that include the second

messenger systems (Thase, 2000; Dubovsky and Buzan, 1999; Thase and Howland,

1995). The bidirectional actions of second messengers allow unitary changes in

second messenger function to produce diverse changes in transmitter synthesis

and release, and in receptor activity, leading to complex neurotransmitter and

receptor effects. There is evidence that mood-stabilizing drugs (e.g., lithium)

act upon G proteins or other second messengers (Jesberger and Richardson, 1985;

Kofman and Belmaker, 1993; Wang et al.,

2001; Chen et al., 2001).

Related Topics