Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Tracheoesophageal Fistula

How is the patient with a TEF managed intraoperatively?

How is

the patient with a TEF managed intraoperatively?

The optimal surgical management is a one-stage

repair, where the fistula is ligated and the proximal and distal ends of the

esophagus are primarily anastomosed. The approach is typically through a right

thoracotomy incision, with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position.

In the presence of a right aortic arch, a left thoracotomy may be performed.

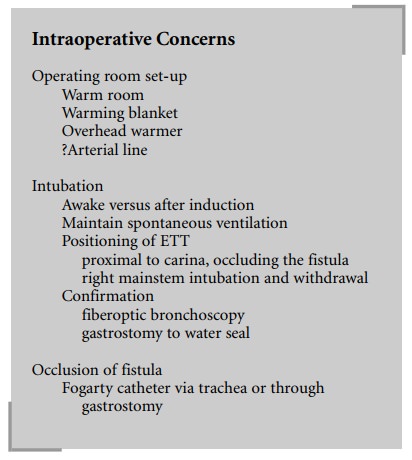

The anesthetic management includes warming of

the operating room and the use of a warming blanket and a radiant overhead

warmer. Standard monitors are applied. An intravenous catheter is placed prior

to induction, if one is not already present. An arterial catheter may be

necessary in high-risk infants. A precordial stethoscope should be securely

positioned in the left axilla for detection of intra-operative airway

obstruction. The esophageal pouch is suctioned and the patient is preoxygenated.

Atropine 0.02 mg/kg may be administered intravenously to prevent bradycardia

during laryngoscopy.

A gastrostomy tube may be placed to decompress

the stomach. However, this may result in a further loss of ven-tilation through

the fistula during positive pressure venti-lation, necessitating clamping of

the gastrostomy tube. Once a common practice, a gastrostomy tube is usually not

placed nowadays, as it may increase the incidence of gastro-esophageal reflux

later in life. If a gastrostomy is per-formed, it is usually accomplished under

local anesthesia prior to induction. It can then be used to aid in the

place-ment of the endotracheal tube (ETT). If the gastric disten-tion does not

impair ventilation, the surgeon may perform the gastrostomy after induction of

general anesthesia.

The optimal anesthetic management of these

patients is to maintain spontaneous ventilation until the fistula is ligated.

Positive pressure ventilation is avoided because it can result in insufflation

of the stomach via the fistula or loss of ventilation through the gastrostomy.

Gastric disten-tion may compromise ventilation and may also lead to aspiration

of gastric contents via the fistula. However, it is not always feasible to

maintain spontaneous ventilation.

Awake intubation is the safest approach. It

allows airway reflexes to be maintained and also allows appropriate

posi-tioning of the ETT without positive pressure ventilation. The

administration of supplemental oxygen during laryn-goscopy can be achieved with

the use of an oxyscope. Awake intubation, however, may be difficult and

traumatic in a vigorous infant. Alternatively, an inhalation or intravenous

induction may be performed without muscle relaxation, thus allowing the infant

to continue to breathe spontaneously.

If a

muscle relaxant is used, care must be taken during positive pressure

ventilation to avoid excessive insufflation of the stomach via the fistula.

Placement and positioning of the ETT can be

tricky. To avoid intubating the fistula, which is located on the poste-rior

aspect of the trachea, the ETT should be inserted with the bevel facing

posteriorly. After intubation, the bevel is rotated anteriorly to avoid

ventilating the fistula.

Since the fistula is usually located just

proximal to the carina, positioning the ETT so that it is above the carina but

still occluding the fistula may be difficult. One com-monly used method is to

insert the ETT (without a Murphy eye) into the right mainstem bronchus and then

gradually withdraw it until breath sounds are heard on the left. However, this

does not always assure that the endotracheal tube occludes the fistula. If a

gastrostomy tube is in place, the distal end is submerged in a beaker of water

and if bubbling occurs there is leakage through the fistula. The ETT is then

advanced until the bubbling ceases while still maintaining left-sided breath

sounds. The gastrostomy tube may be left to water seal during the surgery,

which allows for continued monitoring for ventilation through the fistula.

A second method of confirming placement of the

ETT is with the use of a fiberoptic bronchoscope. After intuba-tion, the

fiberoptic bronchoscope is passed through the ETT and the carina is visualized.

Upon withdrawal of the bronchoscope, if the fistula is not visualized then the

ETT is appropriately positioned. If the fistula is visualized, the ETT is

advanced making sure that its tip remains above the carina.

Sometimes, with a large fistula or one that is

located at or distal to the carina, placement of the ETT to avoid ventilating

the fistula is not possible. In this situation, the fistula may need to be

occluded with a Fogerty balloon catheter placed from above with the help of a

broncho-scope or from below through the gastrostomy.

Once positioned, the ETT should be carefully

secured. After the patient is positioned in the left lateral decubitus

position, reconfirmation of the position of the ETT may be necessary.

Loss of breath sounds and the end-tidal carbon

dioxide (ETCO2) tracing commonly occurs during surgery second-ary to

airway obstruction. This may be due to the accumu-lation of secretions or blood

in the ETT. More often, however, it results from kinking of the trachea during

sur-gical manipulation. The surgeon should immediately be instructed to release

the surgical traction.

Related Topics