Chapter: Clinical Anesthesiology: Anesthetic Management: Anesthesia for Patients with Neuromuscular Disease

Anesthesia for Myasthenia Gravis

MYASTHENIA GRAVIS

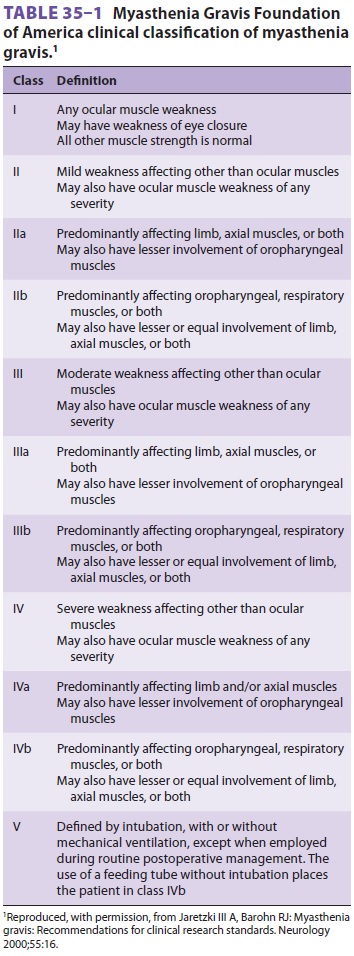

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disorder

char-acterized by weakness and easy fatigability of skele-tal muscle. It is

classified according to disease distribution and severity ( Table

35–1). The preva-lence is estimated at 50–200 per

million population. The incidence is highest in women during their third

decade, and men exhibit two peaks, one in the third decade and another in the

sixth decade.Weakness associated with myasthenia gravis is due to autoimmune

destruction or inactivationof postsynaptic acetylcholine receptors at the

neuro-muscular junction, leading to reduced numbers of receptors and

degradation of their function, and to complement-mediated damage to the

postsynap-tic end plate. IgG antibodies against the nicotinic acetylcholine

receptor in neuromuscular junctions are found in 85–90% of patients with

generalized myasthenia gravis and up to 50–70% of patients with ocular

myasthenia. Among patients with myas-thenia, 10–15% percent develop thymoma,

whereas approximately 70% exhibit histologic evidence of thymic lymphoid

follicular hyperplasia. Other autoimmune-related disorders (hypothyroidism,

hyperthyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis, and sys-temic lupus erythematosus) are

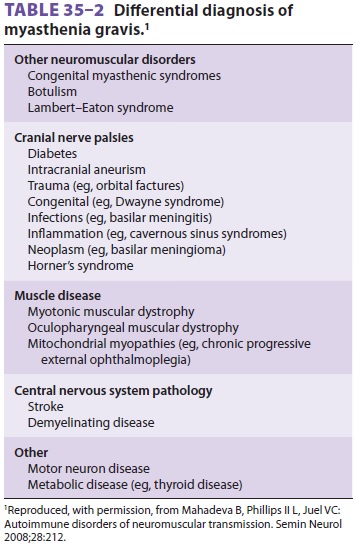

also present in up to 10% of patients. The differential diagnosis of

myas-thenia gravis includes a number of other clinical conditions that may

mimic its signs and symptoms

(Table 35–2). Myasthenia gravis crisis is an exacer-bation

requiring mechanical ventilation and should be suspected in any patient with

respiratory failure of unclear etiology.

The course of myasthenia gravis is marked by

exacerbations and remissions, which may be par-tial or complete. The weakness can

be asymmetric, confined to one group of muscles, or generalized. Ocular muscles

are most commonly affected, result-ing in fluctuating ptosis and diplopia. With

bulbar involvement, laryngeal and pharyngeal muscle weakness can result in

dysarthria, difficulty in chew-ing and swallowing, problems clearing

secretions, or pulmonary aspiration. Severe disease is usually also associated

with proximal muscle weakness (primar-ily in the neck and shoulders) and

involvement of respiratory muscles. Muscle strength characteristi-cally

improves with rest but deteriorates rapidly with exertion. Infection, stress,

surgery, and pregnancy

have unpredictable effects on the disease but often lead to

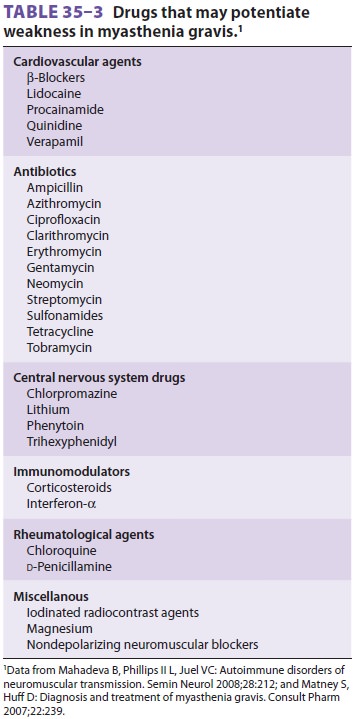

exacerbations. A number of medications may exacerbate the signs and symptoms of

myasthenia gravis ( Table 35–3).

Anticholinesterase drugs are used most

com-monly to treat the muscle weakness of this disorder. These drugs increase

the amount of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction through inhibition of

end plate acetylcholinesterase. Pyridostigmine is prescribed most often; when

given orally, it has an effective duration of 2–4 h. Excessive administra-tion

of an anticholinesterase may precipitate cho-linergic

crisis, which is characterized by increasedweakness and excessive

muscarinic effects, includ-ing salivation, diarrhea, miosis, and bradycardia.

An edrophonium (Tensilon) test may

help differenti-ate a cholinergic from a myasthenic crisis. Increased weakness

after administration of up to 10 mg of intravenous edrophonium indicates

cholinergic cri-sis, whereas increasing strength implies myasthenic crisis. If

this test is equivocal or if the patient clearly has manifestations of

cholinergic hyperactivity, all cholinesterase drugs should be discontinued and

the patient should be monitored in an intensive care unit or close-observation

area. Anticholinesterase drugs are often the only agents used to treat patients

with mild disease. Moderate to severe disease is treated with a combination of

an anticholinesterase drug and immunomodulating therapy. Corticosteroids are

usually tried first, followed by azathioprine, cyclo-sporine, cyclophosphamide,

mycophenolate mofetil, and intravenous immunoglobulin. Plasmapheresis is

reserved for patients with dysphagia or respira-tory failure, or to normalize

muscle strength preop-eratively in patients undergoing a surgical procedure,

including thymectomy. Up to 85% of patients younger than 55 years of age show

clinical improvement fol-lowing thymectomy even in the absence of a tumor, but

improvement may be delayed up to several years.

Anesthetic Considerations

Patients with myasthenia gravis may present

for thymectomy or for unrelated surgical or obstetric procedures, and medical

management of their con-dition should be optimized prior to the intended

procedure. Myasthenic patients with respiratory and oropharyngeal weakness

should be treated preop-eratively with intravenous immunoglobulin or

plas-mapheresis. If strength normalizes, the incidence of postoperative

respiratory complications should be similar to that of a nonmyasthenic patient

under-going a similar surgical procedure. Patients sched-uled for thymectomy

may have deteriorating muscle strength, whereas those undergoing other elective

procedures may be well controlled or in remis-sion. Adjustments in

anticholinesterase medication, immunosuppressants, or steroid therapy in the

peri-operative period may be necessary. Patients with advanced generalized

disease may deteriorate signif-icantly when anticholinesterase agents are

withheld. These medications should be restarted when the patient resumes oral

intake postoperatively. When necessary, cholinesterase inhibitors can also be

given parenterally at 301 the oral dose. Potential problems associated

with management of anticholinesterase therapy in the postoperative period

include altered patient requirements, increased vagal reflexes, and the

possibility of disrupting bowel anastomoses sec-ondary to hyperperistalsis.

Moreover, because these agents also inhibit plasma cholinesterase, they could theoretically prolong the duration of

ester-type localanesthetics and succinylcholine.

Preoperative evaluation should focus on the

recent course of the disease, the muscle groups affected, drug therapy, and

coexisting illnesses.Patients who have myasthenia gravis with respiratory

muscle or bulbar involvement areat increased risk for pulmonary aspiration.

Premedication with metoclopramide or an H2 blocker or proton pump inhibitor may decrease this risk. Because patients

with myasthenia are often very sensitive to the respiratory depressant effect

of opioids and benzodiazepines, premedication with these drugs should be done

with caution, if at all.

With the exception of NMBs, standard

anes-thetic agents may be used in patients with myasthe-nia gravis. Marked

respiratory depression, however, may be encountered following even moderate

doses of propofol or opioids. When general anesthesia is required, a volatile

agent–based anesthetic is fre-quently employed. Deep anesthesia with a volatile

agent alone in patients with myasthenia may provide sufficient relaxation for

tracheal intubation and most surgical procedures, and many clinicians

rou-tinely avoid NMBs entirely. The response to succi-nylcholine is said to be

unpredictable, but we have not found this to be so in practice. Patients may

manifest a relative resistance, or a moderately pro-longed effect . The dose of

succinyl-choline may be increased to 2 mg/kg to overcome any resistance,

expecting that the duration of paraly-sis could be increased by 5–10 min. Many

patients with myasthenia gravis are exquisitely sensitive to nondepolarizing

NMBs.Even a defasciculating dose in some patients may result in nearly complete

paralysis. If NMBs are necessary, small doses of a relatively short-acting

nondepolarizing agent are preferred. We have not found nondepolarizing NMBs to

be necessary during thymectomy with volatile anesthesia. Neuromuscular blockade

should be monitored very closely with a nerve stimulator, and ventilatory function

should be evaluated carefully prior to extubation.

Patients who have myasthenia gravis are at

risk for postoperative respiratory failure. Diseaseduration of more than 6

years, concomitant pulmo-nary disease, peak inspiratory pressure of less than −25 cm H2O (ie, −20 cm H2O), vital capacity lessthan 4 mL/kg, and

pyridostigmine dose greater than 750 mg/d are predictive of the need for

postopera-tive ventilation following thymectomy.

Women with myasthenia can experience increased weakness in the last trimester

of pregnancy and in the early postpartum period. Epidural anesthe-sia is

generally preferable for these patients because it avoids potential problems

with respiratory depression and NMBs related to general anesthesia. Excessively

high levels of motor blockade, however, can also result in hypoventilation.

Infants of myasthenic mothers may show transient myasthenia for 1–3 weeks

follow-ing birth, induced by transplacental transfer of ace-tylcholine receptor

antibodies, which may necessitate intubation and mechanical ventilation.

Related Topics