Chapter: Clinical Cases in Anesthesia : Mitral Stenosis

What is the etiology and pathophysiology of mitral stenosis?

What is

the etiology and pathophysiology of mitral stenosis?

Mitral stenosis is frequently rheumatic in

origin. In many patients, there is a latency period of 30–40 years between the

episode of rheumatic fever and the onset of clinical symptoms. Dyspnea is the

most common symp-tom. The initial presentation is often due to an episode of

atrial fibrillation or to an unrelated condition, such as preg-nancy,

thyrotoxicosis, anemia, or sepsis. Other common symptoms include fatigue,

palpitations, or hemoptysis.

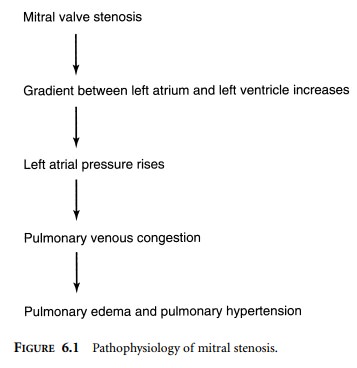

In the normal adult, the mitral valve orifice

is 4–6 cm2. As the orifice narrows, to less than 2 cm2,

the pressure gradient between the left atrium and left ventricle must increase

to maintain adequate flow. The high left atrial pressure causes pulmonary

venous congestion, which eventually leads to pulmonary edema, particularly in

the presence of tachycardia (Figure 6.1). Tachycardia shortens diastole and

diminishes the time available for flow across the mitral valve. This, in turn,

impairs left atrial emptying and left ventricular filling. Cardiac output

decreases, pulmonary congestion increases, and decompensation ensues. A mitral

valve area less than 1.0 cm2 is considered critical. The decision to

perform valve surgery, however, is usually based on the severity of symp-toms

(i.e., New York Heart Association Classification).

Although the left ventricle is “protected” from pressure or volume overload, left ventricular contractility may be impaired by rheumatic involvement of the

papillary muscles and mitral annulus. Left ventricular function might also be

impaired by a shift of the interventricular septum due to right ventricular

(RV) pressure overload. Pulmonary hyper-tension and RV failure are often

observed in mitral stenosis.

Related Topics