Chapter: Fundamentals of Database Systems : Object, Object-Relational, and XML: Concepts, Models, Languages, and Standards : XML: Extensible Markup Language

Structured, Semistructured, and Unstructured Data

Structured, Semistructured, and Unstructured Data

The information stored in databases is known as structured data because it is represented in a strict format. For

example, each record in a relational database table— such as each of the tables

in the COMPANY database in Figure 3.6—follows the same format as the other records in

that table. For structured data, it is common to care-fully design the database

schema using techniques such as those described in Chapters 7 and 8 in order to

define the database structure. The DBMS then checks to ensure that all data

follows the structures and constraints specified in the schema.

However, not all data is collected and inserted into carefully designed

structured databases. In some applications, data is collected in an ad hoc

manner before it is known how it will be stored and managed. This data may have

a certain structure, but not all the information collected will have the

identical structure. Some attrib-utes may be shared among the various entities,

but other attributes may exist only in a few entities. Moreover, additional

attributes can be introduced in some of the newer data items at any time, and

there is no predefined schema. This type of data is known as semistructured data. A number of data

models have been introduced for representing semistructured data, often based

on using tree or graph data structures rather than the flat relational model

structures.

A key difference between structured and semistructured data concerns how

the schema constructs (such as the names of attributes, relationships, and entity

types) are handled. In semistructured data, the schema information is mixed in with the data values, since

each data object can have different attributes that are not known in advance.

Hence, this type of data is sometimes referred to as self-describing data. Consider the following example. We want to

collect a list of bibliographic references related to a certain research

project. Some of these may be books or technical reports, others may be

research articles in journals or conference proceedings, and still others may

refer to complete journal issues or conference proceedings. Clearly, each of

these may have different attributes and different types of information. Even

for the same type of reference—say, conference articles—we may have different

information. For example, one article citation may be quite complete, with full

information about author names, title, proceedings, page numbers, and so on,

whereas another citation may not have all the information available. New types

of bibliographic sources may appear in the future—for instance, references to

Web pages or to conference tutori-als—and these may have new attributes that

describe them.

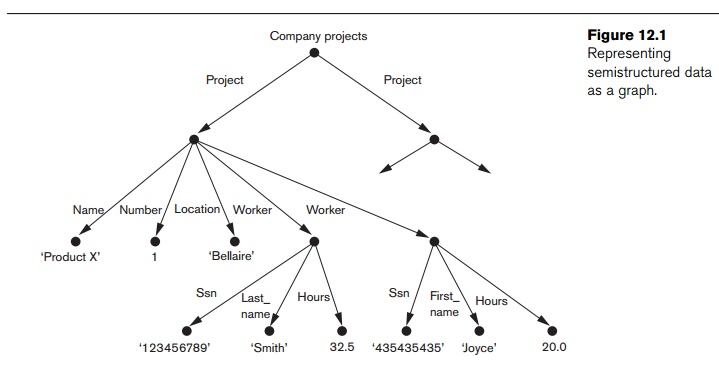

Semistructured data may be displayed as a directed graph, as shown in

Figure 12.1. The information shown in Figure 12.1 corresponds to some of the

structured data shown in Figure 3.6. As we can see, this model somewhat

resembles the object model (see Section 11.1.3) in its ability to represent

complex objects and nested structures. In Figure 12.1, the labels or tags on the

directed edges represent the schema names: the names of attributes, object types (or entity types or classes),

and relationships. The internal nodes

represent individual objects or composite attrib-utes. The leaf nodes represent

actual data values of simple (atomic) attributes.

There are two main differences between the semistructured model and the

object model that we discussed in Chapter 11:

The schema information—names of

attributes, relationships, and classes (object types) in the semistructured

model is intermixed with the objects and their data values in the same data

structure.

In the semistructured model,

there is no requirement for a predefined schema to which the data objects must

conform, although it is possible to define a schema if necessary.

In addition to structured and semistructured data, a third category

exists, known as unstructured data because

there is very limited indication of the type of data. A typical example is a text document that contains information

embedded within it. Web pages in HTML that contain some data are considered to

be unstructured data. Consider part of an HTML file, shown in Figure 12.2. Text

that appears between angled brackets, <...>, is an HTML tag. A tag with a slash, </...>, indicates an end tag, which represents the ending of the effect of a matching start tag. The tags mark

Figure 12.2

Part of an HTML document

representing unstructured data.

<HTML>

<HEAD>

...

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H1>List of company

projects and the employees in each project</H1> <H2>The ProductX

project:</H2>

<TABLE width=“100%”

border=0 cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0> <TR>

<TD

width=“50%”><FONT size=“2” face=“Arial”>John

Smith:</FONT></TD> <TD>32.5 hours per week</TD>

</TR>

<TR>

<TD

width=“50%”><FONT size=“2” face=“Arial”>Joyce

English:</FONT></TD> <TD>20.0 hours per week</TD>

</TR>

</TABLE>

<H2>The ProductY

project:</H2>

<TABLE width=“100%”

border=0 cellpadding=0 cellspacing=0> <TR>

<TD

width=“50%”><FONT size=“2” face=“Arial”>John

Smith:</FONT></TD> <TD>7.5 hours per week</TD>

</TR>

<TR>

<TD

width=“50%”><FONT size=“2” face=“Arial”>Joyce

English:</FONT></TD> <TD>20.0 hours per week</TD>

</TR>

<TR>

<TD width=

“50%”><FONT size=“2” face=“Arial”>Franklin

Wong:</FONT></TD> <TD>10.0 hours per week</TD>

</TR>

</TABLE>

...

</BODY>

</HTML>

up the document in order to instruct an HTML processor how to display the text between a start tag and a matching end

tag. Hence, the tags specify document for-matting rather than the meaning of

the various data elements in the document. HTML tags specify information, such

as font size and style (boldface, italics, and so on), color, heading levels in

documents, and so on. Some tags provide text structur-ing in documents, such as

specifying a numbered or unnumbered list or a table. Even these structuring

tags specify that the embedded textual data is to be displayed in a certain

manner, rather than indicating the type of data represented in the table.

HTML uses a large number of predefined tags, which are used to specify a

variety of commands for formatting Web documents for display. The start and end

tags spec-ify the range of text to be formatted by each command. A few examples

of the tags shown in Figure 12.2 follow:

The <HTML> ... </HTML> tags specify the boundaries of

the document.

The document header information—within the <HEAD> ... </HEAD> tags—specifies various

commands that will be used elsewhere in the docu-ment. For example, it may

specify various script functions in

a language such as JavaScript or PERL, or certain formatting styles (fonts, paragraph styles, header styles, and so

on) that can be used in the document. It can also specify a title to indicate

what the HTML file is for, and other similar infor-mation that will not be

displayed as part of the document.

The body of the document—specified within the <BODY> ... </BODY> tags—includes the document

text and the markup tags that specify how the text is to be formatted and

displayed. It can also include references to other objects, such as images,

videos, voice messages, and other documents.

The <H1> ... </H1> tags specify that the text

is to be displayed as a level 1 heading. There are many heading levels (<H2>, <H3>, and so on), each dis-playing text in a less prominent heading

format.

The <TABLE> ... </TABLE> tags specify that the

following text is to be dis-played as a table. Each table row in the table is enclosed within <TR> ...

</TR> tags, and the individual table data elements in a row are displayed within <TD> ... </TD> tags.

Some tags may have attributes, which appear within the start tag and describe additional properties of the tag.

In Figure 12.2, the <TABLE> start tag has four

attributes describing various characteristics of the table. The following <TD> and <FONT> start tags have one and two

attributes, respectively.

HTML has a very large number of predefined tags, and whole books are

devoted to describing how to use these tags. If designed properly, HTML

documents can be formatted so that humans are able to easily understand the

document contents, and are able to navigate through the resulting Web

documents. However, the source HTML text documents are very difficult to

interpret automatically by computer

pro-grams because they do not include schema information about the type of

data in the documents. As e-commerce

and other Internet applications become increasingly automated, it is becoming

crucial to be able to exchange Web documents among various computer sites and

to interpret their contents automatically. This need was one of the reasons

that led to the development of XML. In addition, an extendible version of HTML

called XHTML was developed that allows users to extend the tags of HTML for

different applications, and allows an XHTML file to be interpreted by standard

XML processing programs. Our discussion will focus on XML only.

The example in Figure 12.2 illustrates a static HTML page, since all the information to be displayed is

explicitly spelled out as fixed text in the HTML file. In many cases, some of

the information to be displayed may be extracted from a database. For example,

the project names and the employees working on each project may be extracted

from the database in Figure 3.6 through the appropriate SQL query. We may want

to use the same HTML formatting tags for displaying each project and the

employees who work on it, but we may want to change the particular projects

(and employees) being displayed. For example, we may want to see a Web page

displaying the information for ProjectX,

and then later a page displaying the information for ProjectY. Although both pages are displayed using the same HTML

formatting tags, the actual data

items displayed will be different. Such Web pages are called dynamic, since the data parts of the

page may be different each time it is displayed, even though the display

appearance is the same.

Related Topics