Chapter: Surgical Pathology Dissection : General Approach to Surgical Pathology Specimens

Step 4. Specimen Sampling

Step 4. Specimen Sampling

Mindless

sampling of a specimen introduces errors at two different extremes. At one

extreme, tissue sampling is inadequate, either because the number of sections

is too few or the quality of sections is too poor. In these instances,

important issues cannot be adequately addressed in the surgical pathology

report. Forgetting to assess a surgical margin, failing to determine the extent

of local tumor infiltration, and neglecting to check for metastases to regional

lymph nodes are com-mon examples of inadequate sampling. At the other extreme,

tissue sampling can be excessive. An inordinate number of tissue sections may

exact a costly toll on the resources of the surgical pathology laboratory.

The key

to an approach that is both economical and thorough is selective sampling. Selective sam-pling is a strategic approach

which attempts to maximize the information that can be obtained from a given

tissue section. As opposed to ran-dom and indiscriminant sampling of a

specimen, tissue sampling that is selective increases the information that can

be obtained histologically, and it requires fewer sections to do so. Appendix

1-C lists some fundamental guidelines for selective tissue sampling.

Sampling a Tumor

The

goals of tumor sampling go beyond the ques-tion of ‘‘What is it?’’ Tumor

sampling is con-cerned not just with the type of a tumor but also with its

histologic grade and the degree to which it has extended into surrounding

structures. A tumor should be sampled with the objective of addressing all

three of these issues.

In

general, most sections of a tumor should be obtained from its periphery. This

peripheral zone is often the best preserved region of a tumor, while the

central zone is frequently so necrotic that it yields no useful histologic

information. In addition, the tumor’s periphery demonstrates the interface of

the tumor with adjacent tissues. This interface zone may provide evidence

regarding where a tumor has arisen (e.g., colorectal carci-noma arising in a

pre-existing villous adenoma);

important

clues about the biologic behavior of the tumor (e.g., transcapsular invasion of

a follicular thyroid carcinoma); and information regarding the degree of local

tumor invasion (e.g., depth of invasion of a cancer into the wall of the

colon).

Questions

frequently arise regarding the number of sections that should be taken of a

tumor. Unfortunately, there is no single answer, since the appropriate number

of sections depends on the type of specimen. For example, a single section from

a solitary liver nodule may be suffi-cient to confirm that it is a metastasis,

but such limited sectioning of a solitary thyroid nodule may not allow

distinction between a follicular adenoma and a follicular carcinoma. Despite

this tremendous variability between specimens, a few general considerations should

guide the sam-pling of a tumor. First, when trying to assess the histologic

type and grade of a neoplasm, be sure to sample all areas of the tumor that, on

gross inspection, appear different. Even strict adher-ence to rigid rules such

as ‘‘one section per 1 cm of tumor’’ may not be adequate if the sections are

not selectively taken from areas of the tumor that appear grossly distinct.

Second, sections of large cysts should be taken from areas where the cyst wall

appears thickened or where the cyst lining has a complex appearance (e.g.,

shaggy, papillary excrescences). Sections from these areas are most likely to

reveal the prolifera-tive areas of the cyst lining and to demonstrate tumor

infiltration of the cyst wall. Third, when concern exists about malignant

transformation within a benign lesion or premalignant process, the lesion

should be extensively if not entirely submitted for histologic evaluation. A

number of examples fall under this category, including mucinous cystic

neoplasms of the ovary and pancreas, adenomas of the gastrointestinal tract,

Barrett’s esophagus with dysplasia, in

situ transitional carcinoma of the urinary bladder, and many others.

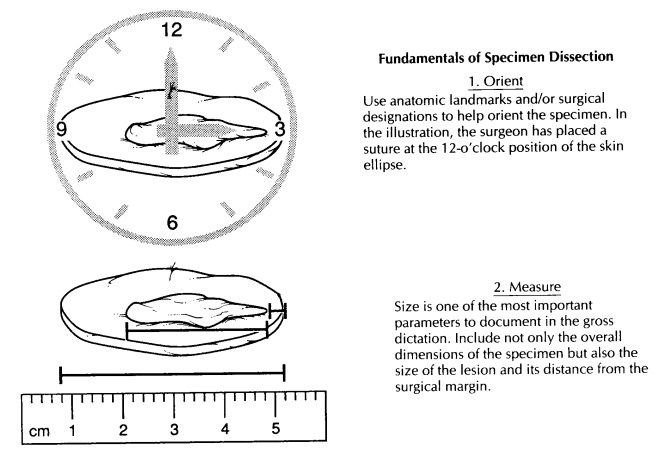

Sampling a Margin

The margin is the edge or the boundary of the specimen. It represents the plane where the sur-geon has sectioned across tissues to remove the specimen from the patient. The surgical margin may be free of disease; that is, a rim of uninvolved tissues may surround a pathologic lesion that has been completely resected. Alternatively, the lesion could extend to the edge of the specimen, implying that the lesion has not been completely removed. Clearly, the status of a surgical margin is an important indicator of the potential for the disease to recur and of the need for further ther-apy. Therefore, the assessment of these margins, both grossly and microscopically, is of consider-able importance.

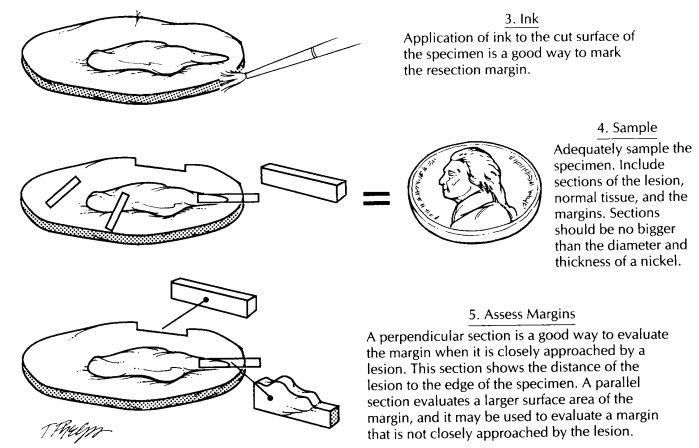

As illustrated, margins can be sampled in one of two ways: They can be taken as either as per-pendicular section or a parallel section. A perpen-dicular section is one taken at a right angle to the edge of the specimen. In this type of section, the true margin is present at one of the two ends of the section. The advantage of a perpendicular section is that it can be used to demonstrate the relationship of the edge of the tumor to the margin. A perpendicular section allows the im-portant distinction between a lesion that truly extends to the margin and a lesion that very closely approaches but does not involve the margin. Since only a small surface area of the margin is represented in a perpendicular section, the margin must be carefully inspected and then selectively sampled from those areas where it is most closely approached by the tumor.

A shave

section is one taken parallel to the edge of the specimen. Because the entire

shave section spans the margin, a relatively large surface area at the margin

can be evaluated with a single sec-tion. A shave section is ideal for obtaining

com-plete cross sections of small luminal or cylindrical structures. Unlike the

perpendicular section, the shave section does not effectively demonstrate the

relationship between the margin and the edge of the tumor. Its major drawback

is that it cannot be used to distinguish between a lesion that truly extends to

the margin and one that very closely approaches but does not actually involve

the margin. For this reason, shave sections should be reserved for those

instances when the margin appears widely free of tumor or when dealing with

small luminal or cylindrical structures that are not easily sampled using

perpendicular sections.

To help

the pathologist interpret the histo-logic findings, the slide index portion of

the gross description should clearly document how the margin was sampled. The

presence of tumor in a margin section may have entirely different implications,

depending on whether the margin was sampled using a perpendicular or parallel

section.A specimen dissection is not complete until the lymph nodes, when

present, have been found and sampled. Sampling of lymph nodes is especially

important for resections of neoplasms where criti-cal staging information may

depend on the num-ber and location of lymph nodes involved by metastatic tumor.

Although

the lymph node status is clearly important in staging neoplasms, finding these

lymph nodes can be a tedious and frustrating job. They may be small,

inconspicuous, and entirely overshadowed by the fibroadipose tissues in which

they are embedded. Skill at finding lymph nodes develops over time, but a few

guidelines may enhance the efficiency of your search. First, it is generally

best to orient the specimen, desig-nate the various regional lymph node levels,

and submit margins of the soft tissues before a lymph node dissection is

undertaken. Keep in mind that lymph node dissections require significant

distor-tion and manipulation of the soft tissues such that the specimen may not

be easily reconstructed following a thorough search for lymph nodes. Second,

many prefer to look for lymph nodes in the fresh specimen. Lymph nodes are

often best appreciated by touch, and smaller lymph nodes may elude detection

when the surrounding soft tissues have been hardened by fixation.

Lymph

nodes larger than 5 mm should be seri-ally sectioned at 2- to 3-mm intervals. A

common error is to submit multiple slices from more than one lymph node in the

same tissue cassette for histologic evaluation. This may cause consider-able

confusion regarding the number of involved lymph nodes if more than one tissue

fragment contains metastatic tumor. To avoid this confu-sion, a given cassette

should contain slices from only one lymph node.

Sampling Normal Tissues

Even

tissues that do not appear to be involved by a pathologic process should be

sampled for histologic evaluation. Histologic evaluation can uncover diseases

that may not have been appreci-ated on gross inspection. These microscopic

alter-ations may be entirely unrelated to the primary lesion, or they may be

closely associated findings that provide important insight into the origin of

the primary lesion. It is also important to sample normal tissues to document

the structures that were surgically removed. For example, a section taken from

the adrenal gland in a radical nephrec-tomy specimen clearly documents that

this organ was removed, identified, and examined.

Related Topics