Chapter: Essentials of Psychiatry: Physician–Patient Relationship

Special Issues in the Physician–Patient Relationship

Special Issues in the

Physician–Patient Relationship

Phase of Treatment

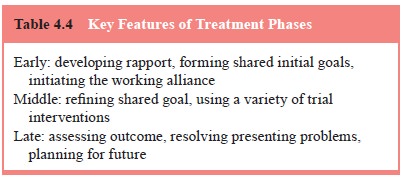

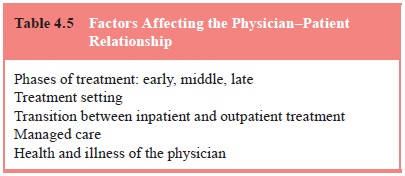

The treatment phase – early, middle, or late (Table

4.4) – affects the structure of the physician–patient relationship in terms of

both the issues to be addressed and the task to be accomplished by the

physician and the patient. The early stage of treatment involves developing a

rapport, forming shared initial goals, and initiating the working alliance.

Education of the patient is important to the success of the physician–patient

relationship in this stage, so that the patient learns what he or she can

expect. In the middle stage of treatment, the physician and patient

continuously refine their shared goals, and various interventions are tried.

While this takes place, transference and countertransference are likely to

emerge. How these are recognized and managed is critical to whether the

relationship continues and is therapeutic.

In the later phase of treatment, the assessment of

the out-come and plans for the future are the primary focus. The phy-sician and

the patient discuss the end of their relationship in a process known as

termination. Successes and disappointments associated with the treatment are

reviewed. The physician must be willing to acknowledge the patient’s

disappointments, as well as recognize her or his own disappointments in the treatment.

The therapeutic alliance is strengthened in this stage when the physician

accepts expressions of the patient’s disappointments, encourages such

expressions when they are not forthcoming,

and prepares the patient for the future. Such

preparations in-clude orienting the patient as to when he or she might seek

fur-ther treatment (Ursano and Silberman, 2002). Solidifying the

physician–patient relationship at the end of the treatment can be critical to

the patient’s self-esteem and willingness to return if symptoms reappear (Table

4.5).

As a part of the termination process the physician

and the patient must review what has been learned, discuss what changes have

taken place in the patient and the patient’s life, and acknowledge together the

sadness and joy of their leave-taking. The termination involves a mourning

process even when treatment has been brief or unpleasant. Of course, when the

physician–patient relationship has been rewarding, and both physician and

patient are satisfied with what they have accom-plished, mourning is more

intense and often characterized by a bittersweet sadness.

Treatment Settings

The physician–patient relationship takes place in a

variety of treatment settings. These include the private office, community clinic,

emergency room, inpatient psychiatric ward and general hospital ward.

Psychiatrists treating patients in a private office may find that the relative

privacy of this setting enhances the early establishment of trust related to

confidentiality. In addi-tion, the psychiatrist’s personality is more evident

in the private office where personal factors influencing choice of decor, room

arrangement and location play a role. However, in contrast to the hospital or

community setting, the private office generally lacks other evidence of the

physician’s competence and humanness. In hospital and community settings, when

a colleague greets the physician and the patient in the hall, or the physician

receives a call for a consultation by a colleague or for a meeting, it

indicates to the patient that the physician is qualified, skilled and humane.

On the other hand, therapeutic work conducted in

the com-munity clinic, emergency room and general hospital ward often requires

the psychiatrist and patient to adapt rapidly to meeting one another, assessing

the problem, establishing treatment goals, and ensuring the appropriate

interventions and follow-up. The importance of protecting the patient’s needs

for time, predictabil-ity and structure can run counter to the demands of a

busy serv-ice and unexpected clinical and administrative requirements. The

psychiatrist must stay alert to the patient’s perspective but not all

interruptions can be avoided. The patient can be informed and accommodated as

much as possible, and any feelings of hurt, disappointment, or anger can be

listened for by the physician and responded to empathically. At times,

patients, particularly those with borderline personality disorder, may require

transfer to an-other psychiatrist whose schedule can accommodate the patient’s

exquisite needs for stability.

The boundaries of confidentiality are necessarily

extended in hospital and community settings to include consultation withother

physicians, nursing staff and often family members (Wise and Rundell, 2002).

Particular attention must always be given to the patient’s need for and right

to respect and privacy. Regardless of the setting, patients receiving

medication must be fully informed about the potential risks and benefits of and

alternatives to the recommended pharmacological treatment (Kessler, 1991).

Patients must be educated about the risks and benefits of receiv-ing prescribed

treatment and of not receiving treatment. This is an important component of

maintaining the physician–patient relationship. Patients who are informed about

and involved in de-cisions about medication respect the physician’s role and

interest in their welfare. Psychiatrists must also pay particular attention to

the meaning a patient attaches to any prescribed medication, particularly when

the time comes to alter or discontinue its use (Ursano et al., 1991).

The change from inpatient to outpatient therapy

involves the resumption of a greater degree of autonomy by the patient in the

physician–patient dyad. The physician must actively encour-age this separation

and its hope for the future. This transition is delicate for any therapeutic

pair.

Managed Care

Managed care, broadly defined as any care of

patients that is not determined solely by the provider, currently focuses on

the economic aspects of delivering medical care, with little atten-tion thus

far to its potential effects on the physician–patient relationship (Goodman et

al., 1992). Discontinuity of care and the creation of unrealistic expectations

on the part of patients have been raised as likely deleterious effects on that

relation-ship (Emanuel and Brett, 1993). Other issues that can affect the

physician–patient relationship include the erosion of con-fidentiality,

shrinkage of the types of reimbursable services, and diminished autonomy of the

patient and the physician in medical decision-making. Additionally, many

managed care systems dictate a split treatment model, with the psychiatrist

prescribing psychopharmacologic treatment and a separate clinician providing

psychotherapy. In such a system, there are complicated challenges faced both by

clinicians and patients. With neither party in complete control of decisions,

the physi-cian–patient relationship can become increasingly adversarial and

subservient to external issues such as cost, quality of life, political

expediency and social efficiency (Siegler, 1993).

Related Topics