Chapter: Clinical Pharmacology: Fundamentals of clinical pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacodynamics is the study of the drug

mechanisms that pro-duce biochemical or physiologic changes in the body. The

inter-action at the cellular level between a drug and cellular compo-nents,

such as the complex proteins that make up the cell mem-brane, enzymes, or

target receptors, represents drug action. The response resulting from this drug

action is the drug effect.

It’s the cell that matters

A drug can modify cell function or rate of

function, but it can’t impart a new function to a cell or to target tissue.

Therefore, the drug effect depends on what the cell is capable of

accomplish-ing.

A drug can alter the target cell’s function by:

·

modifying the cell’s physical or chemical environment

·

interacting with a receptor (a specialized location on a cell membrane

or inside a cell).

Agonist drugs

Many drugs work by stimulating or blocking drug

receptors. A drug attracted to a receptor displays an affinity for that

receptor. When a drug displays an affinity for a receptor and stimulates it,

the drug acts as an agonist. An

agonist binds to the receptor and produces a response. This ability to initiate

a response after bind-ing with the receptor is referred to as intrinsic activity.

Antagonist drugs

If a drug has an affinity for a receptor but

displays little or no in-trinsic activity, it’s called an antagonist. An antagonist prevents a response from occurring.

Reversible or irreversible

Antagonists can be competitive or noncompetitive.

·

A competitive antagonist

competes with the agonist for recep-tor sites. Because this type of antagonist

binds reversibly to the re-ceptor site, administering larger doses of an

agonist can overcome the antagonist’s effects.

·

A noncompetitive antagonist

binds to receptor sites and blocks the effects of the agonist. Administering

larger doses of the ago-nist can’t reverse the antagonist’s action.

Regarding receptors

If a drug acts on a variety of receptors, it’s said

to be nonselective and can cause multiple and widespread effects. In addition,

some receptors are classified further by their specific effects. For exam-ple,

beta receptors typically produce increased heart rate and bronchial relaxation

as well as other systemic effects.

Beta receptors, however, can be further divided

into beta1 re-ceptors (which act primarily on the

heart) and beta2 receptors (which act primarily on smooth

muscles and gland cells).

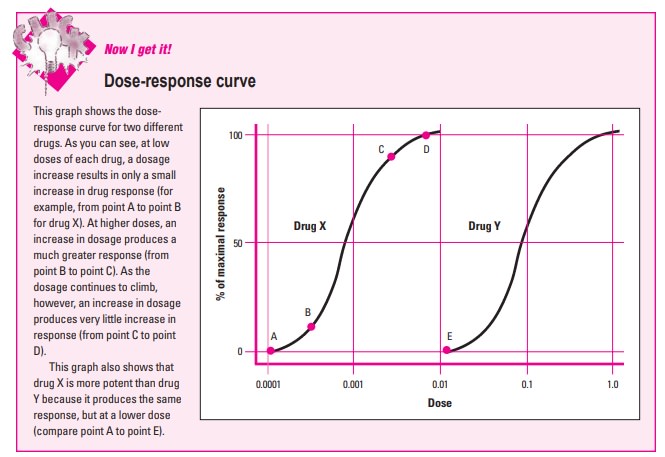

Potent power

Drug potency refers to the relative amount of a

drug required to produce a desired response. Drug potency is also used to

compare two drugs. If drug X produces the same response as drug Y but at a

lower dose, then drug X is more potent than drug Y.

As its name implies, a dose-response curve is used

to graphi-cally represent the relationship between the dose of a drug and the

response it produces. (See Dose-response

curve)

Maximum effect

On the dose-response curve, a low dose usually

corresponds to a low response. At a low dose, a dosage increase produces only a

slight increase in response. With further dosage increases, the drug response

rises markedly. After a certain point, however, an increase in dose yields

little or no increase in response. At this point, the drug is said to have reached

maximum effectiveness.

Margin of safety

Most drugs produce multiple effects. The

relationship between a drug’s desired therapeutic effects and its adverse

effects is called the drug’s therapeutic

index. It’s also referred to as its margin

of safety.

The therapeutic index usually measures the

differ-ence between:

·

an effective dose for 50% of the patients treated

·

the minimal dose at which adverse reactions occur.

Narrow index = potential danger

Drugs with a narrow, or low, therapeutic index have

a narrow margin of safety. This means that there’s a nar-row range of safety

between an effective dose and a lethal one. On the other hand, a drug with a

high thera-peutic index has a wide margin of safety and poses less risk of

toxic effects.

Related Topics