Chapter: Social Research

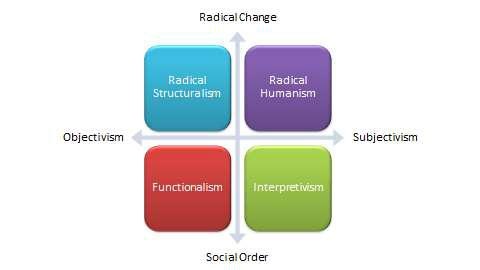

Paradigms of Social Research

.jpg)

Paradigms of Social Research

Our design and conduct of research is shaped

by our mental models or frames of references that we use to organize our

reasoning and observations. These mental models or frames (belief systems) are

called paradigms. The word 'paradigm' was popularized by

Thomas Kuhn (1962) in his book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, where he examined the history of the natural sciences to identify patterns of activities that shape the progress of science. Similar ideas are applicable to social sciences as well, where a social reality can be viewed by different people in different ways, which may constrain their thinking and reasoning about the observed phenomenon. For instance, conservatives and liberals tend to have very different perceptions of the role of government in people's lives, and hence, have different opinions on how to solve social problems. Conservatives may believe that lowering taxes is the best way to stimulate a stagnant economy because it increases people's disposable income and spending, which in turn expands business output and employment. In contrast, liberals may believe that governments should invest more directly in job creation programs such as public works and infrastructure projects, which will increase employment and people's ability to consume and drive the economy. Likewise, Western societies place greater emphasis on individual rights, such as one's r ight to privacy, right of free speech, and right to bear arms. In contrast, Asian societies tend to balance the rights of individuals against the rights of families, organizations, and the government, and therefore tend to be more communal and less individualistic in their policies. Such differences in perspective often lead Westerners to criticize Asian governments for being autocratic, while Asians criticize Western societies for being greedy, having high crime rates, and creating a 'cult of the individual.' Our personal paradigms are like 'colored glasses' that govern how we view the world and how we structure our thoughts about what we see in the world.

Paradigms are often hard to recognize, because

they are implicit, assumed, and taken for granted. However, recognizing these

paradigms is key to making sense of and reconciling differences in people'

perceptions of the same social phenomenon. For instance, why do liberals

believe that the best way to improve secondary education is to hire more

teachers, but conservatives believe that privatizing education (using such

means as school vouchers) are more effective in achieving the same goal?

Because conservatives place more faith in competitive markets (i.e., in free

competition between schools competing for education dollars), while liberals

believe more in labor (i.e., in having more teachers and schools). Likewise, in

social science research, if one were to understand why a certain technology was

successfully implemented in one organization but failed miserably in another, a

researcher looking at the world through a 'rational lens' will look for

rational explanations of the problem such as inadequate technology or poor fit

between technology and the task context where it is being utilized, while

another research looking at the same problem through a 'social lens' may seek

out social deficiencies such as inadequate user training or lack of management

support, while those seeing it through a 'political lens' will look for

instances of organizational politics that may subvert the technology

implementation process. Hence, subconscious paradigms often constrain the

concepts that researchers attempt to measure, their observations, and their

subsequent interpretations of a phenomenon. However, given the complex nature

of social phenomenon, it is possible that all of the above paradigms are

partially correct, and that a fuller understanding of the problem may require

an understanding and application of multiple paradigms.

Two popular paradigms today among social science researchers are positivism and post-positivism. Positivism, based on the works of French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798-1857), was the dominant scientific paradigm until the mid-20th century. It holds that science or knowledge creation should be restricted to what can be observed and measured. Positivism tends to rely exclusively on theories that can be directly tested. Though positivism was originally an attempt to separate scientific inquiry from religion (where the precepts could not be objectively observed), positivism led to empiricism or a blind faith in observed data and a rejection of any attempt to extend or reason beyond observable facts. Since human thoughts and emotions could not be directly measured, there were not considered to be legitimate topics for scientific research. Frustrations with the strictly empirical nature of positivist philosophy led to the development of post-positivism (or postmodernism) during the mid-late 20th century. Post-positivism argues that one can make reasonable inferences about a phenomenon by combining empirical observations with logical reasoning. Post-positivists view science as not certain but probabilistic (i.e., based on many contingencies), and often seek to explore these contingencies to understand social reality better. The post -positivist camp has further fragmented into subjectivists, who view the world as a subjective construction of our subjective minds rather than as an objective reality, and critical realists, who believe that there is an external reality that is independent of a person's thinking but we can never know such reality with any degree of certainty.

Related Topics