Chapter: Fundamentals of Database Systems : Additional Database Topics: Security and Distribution : Database Security

Discretionary Access Control Based on Granting and Revoking Privileges

Discretionary Access Control

Based on Granting and Revoking Privileges

The typical method of enforcing discretionary access control in a database system is based on the granting and revoking of privileges. Let us consider privileges in the context of a relational DBMS. In particular, we will discuss a system of privileges somewhat similar to the one originally developed for the SQL language (see Chapters 4 and 5). Many current relational DBMSs use some variation of this tech-nique. The main idea is to include statements in the query language that allow the DBA and selected users to grant and revoke privileges.

1. Types of Discretionary Privileges

In SQL2 and later versions, the concept of an authorization identifier is used to

refer, roughly speaking, to a user account (or group of user accounts). For

simplicity, we will use the words user

or account interchangeably in place

of authorization identifier. The DBMS must provide selective access to each relation

in the database based on specific

accounts. Operations may also be controlled; thus, having an account does not

necessarily entitle the account holder to all the functionality provided by

the DBMS. Informally, there are two levels for assigning privileges to use the

database system:

The account level. At this level, the DBA specifies the particular

privileges that each account holds

independently of the relations in the database.

The

relation (or table) level. At this

level, the DBA can control the privilege

to access each individual relation or view in the database.

References privilege on R. This

gives the account the capability to reference (or refer to) a relation R

when specifying integrity constraints. This privilege can also be restricted to

specific attributes of R.

Notice that to create a view, the account must

have the SELECT privilege on all relations involved

in the view definition in order to specify the query that corresponds to the view.

2. Specifying Privileges through the Use of

Views

The mechanism of views is an important discretionary

authorization mechanism in its own right. For example, if the owner A of a relation R wants another account B

to be able to retrieve only some fields of R,

then A can create a view V of R

that includes only those attributes and then grant SELECT on V to B. The same applies to limiting B to retrieving only certain tuples of R; a view V can be created by defining the view by means of a query that

selects only those tuples from R that

A wants to allow B to access. We will illustrate this discussion with the example

given in Section 24.2.5.

3. Revoking of Privileges

In some cases it is desirable to grant a

privilege to a user temporarily. For example, the owner of a relation may want

to grant the SELECT privilege to a user for a specific task and then revoke that

privilege once the task is completed. Hence, a mechanism for revoking privileges is needed. In SQL a

REVOKE command is included for the purpose of canceling privileges. We

will see how the REVOKE command is used in the example in Section

24.2.5.

4. Propagation of Privileges Using the

GRANT OPTION

Whenever the owner A of a relation R grants

a privilege on R to another account B, the privilege can be given to B with or without the GRANT OPTION. If the GRANT OPTION is given, this means that B can also grant that privilege on R to other accounts. Suppose that B is given the GRANT OPTION by A

and that B then grants the privilege

on R to a third account C, also with the GRANT OPTION. In this way, privileges on R

can propagate to other accounts

without the knowledge of the owner of R.

If the owner account A now revokes

the privilege granted to B, all the

privileges that B propagated based on

that privilege should automatically be

revoked by the system.

It is possible for a user to receive a certain

privilege from two or more sources. For example, A4 may receive a certain UPDATE R privilege from both A2 and A3. In such a case, if A2 revokes this privilege from A4, A4 will still continue to have the privilege by

virtue of having been granted it from A3. If A3 later revokes the privilege from A4, A4 totally loses the privilege. Hence, a DBMS that allows propagation

of privi-leges must keep track of how all the privileges were granted so that

revoking of priv-ileges can be done correctly and completely.

5. An

Example to Illustrate Granting and Revoking of Privileges

Suppose that the DBA creates four accounts—A1, A2, A3, and A4—and wants only A1

to be able to create base relations. To do

this, the DBA must issue the following GRANT command in SQL:

GRANT CREATETAB TO A1;

The CREATETAB (create table) privilege gives account A1 the capability to create new database tables (base relations) and

is hence an account privilege. This

privilege was part of earlier versions of SQL but is now left to each

individual system imple-mentation to define.

In SQL2 the same effect can be accomplished by

having the DBA issue a CREATE SCHEMA command, as follows:

CREATE SCHEMA EXAMPLE AUTHORIZATION A1;

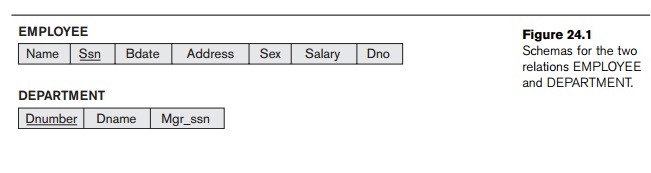

User account A1 can now create tables under the schema called EXAMPLE. To con-tinue our example, suppose that A1 creates the two base relations EMPLOYEE and DEPARTMENT

shown in Figure 24.1; A1 is then the owner of these two relations and hence has all the relation

privileges on each of them.

Next, suppose that account A1 wants to grant to account A2 the privilege to insert and delete tuples in

both of these relations. However, A1 does not want A2 to be able to propagate these privileges to

additional accounts. A1 can issue the following com-mand:

GRANT INSERT, DELETE ON EMPLOYEE,

DEPARTMENT TO A2;

Notice that the owner account A1 of a relation automatically has the GRANT OPTION, allowing it to grant privileges on the

relation to other accounts. However, account A2 cannot grant INSERT and DELETE privileges on the EMPLOYEE and DEPARTMENT tables because

A2 was not given the

GRANT OPTION in the preceding command.

Next, suppose that A1 wants to allow account A3 to retrieve information from either of the two

tables and also to be able to propagate the SELECT privilege to other accounts. A1 can issue the following command:

GRANT SELECT ON EMPLOYEE,

DEPARTMENT TO A3 WITH GRANT OPTION;

The clause WITH

GRANT OPTION means that A3 can now propagate the privilege to other accounts by using GRANT. For example, A3 can grant the SELECT privilege on the EMPLOYEE relation to A4 by issuing the following command:

GRANT SELECT ON EMPLOYEE TO A4;

Notice that A4 cannot propagate the SELECT privilege to other accounts because the GRANT OPTION was not given to A4.

Now suppose that A1 decides to revoke the SELECT privilege on the EMPLOYEE relation from A3; A1 then can issue this command:

REVOKE SELECT ON EMPLOYEE FROM A3;

The DBMS must now revoke the SELECT privilege on EMPLOYEE from A3, and it must also automatically revoke the SELECT privilege on EMPLOYEE from A4. This is because A3 granted that privilege to A4, but A3 does not have the privilege any more.

Next, suppose that A1 wants to give back to A3 a limited capability to SELECT from the EMPLOYEE relation and wants to allow A3 to be able to propagate the privilege. The limitation is to

retrieve only the Name, Bdate, and Address attributes and only for the tuples with Dno = 5. A1 then can create the following view:

CREATE VIEW A3EMPLOYEE AS

SELECT Name, Bdate, Address

FROM EMPLOYEE

WHERE Dno = 5;

After the view is created, A1 can grant SELECT on the view A3EMPLOYEE to A3 as follows:

GRANT SELECT ON A3EMPLOYEE TO A3 WITH GRANT

OPTION;

Finally, suppose that A1 wants to allow A4 to update only the Salary attribute of EMPLOYEE; A1 can then issue the following command:

GRANT UPDATE ON EMPLOYEE (Salary) TO A4;

The UPDATE and INSERT privileges can specify particular attributes

that may be updated or inserted in a relation. Other privileges (SELECT, DELETE) are not attrib-ute specific, because this specificity can easily

be controlled by creating the appro-priate views that include only the desired

attributes and granting the corresponding privileges on the views. However,

because updating views is not always possible (see Chapter 5), the UPDATE and INSERT privileges are given the option to specify the

particular attributes of a base relation that may be updated.

6. Specifying Limits on Propagation of

Privileges

Techniques to limit the propagation of

privileges have been developed, although they have not yet been implemented in

most DBMSs and are not a part of SQL.

Limiting horizontal propagation to

an integer number i means that an

account B given the GRANT OPTION can grant the privilege to at most i other accounts.

Vertical

propagation is more

complicated; it limits the depth of the granting of privileges. Granting a privilege with a vertical propagation of

zero is equivalent to granting the privilege with no GRANT OPTION. If account A grants a privilege to account B

with the vertical propagation set to an integer number j > 0, this means that the account B has the GRANT OPTION on that privilege, but B can grant the privilege to other accounts only with a vertical

propagation less than j. In effect,

vertical propagation limits the sequence of GRANT

OPTIONS that can be given from one account to the next

based on a single original grant of the privilege.

We briefly illustrate horizontal and vertical

propagation limits—which are not available currently in SQL or other

relational systems—with an example. Suppose

that A1 grants SELECT to A2 on the EMPLOYEE relation with horizontal propagation equal to

1 and vertical propagation equal to 2. A2 can then grant SELECT to at most one account because the horizontal

propagation limitation is set to 1. Additionally, A2 cannot grant the privilege to another account except with vertical

propagation set to 0 (no GRANT OPTION) or 1; this is because A2 must reduce the vertical propagation by at least 1 when passing

the privilege to others. In addition, the horizontal propagation must be less

than or equal to the originally granted hor-izontal propagation. For example,

if account A grants a privilege to

account B with the horizontal

propagation set to an integer number j

> 0, this means that B can grant

the privilege to other accounts only with a horizontal propagation less than or equal to j. As this example shows, horizontal and vertical

propagation techniques are designed

to limit the depth and breadth of propagation of privileges.

Related Topics